Mis à jour le Dimanche, 12 Décembre 2021

What we now know about the ugly SARS-CoV-2 virus is that it is among a group of coronaviruses that causes diseases in animals and birds, and respiratory tract infections in humans. These infections tend to be mild, but in rarer forms such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) they can be fatal. SARS-CoV-2 shares a similar sequencing identity with the infamous SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), but SARS-CoV-2 is relatively more infectious in comparison to other CoV. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV are all suspected of being from animal reservoirs and then transmitted to humans.

The current outbreak declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) is caused by SARS-CoV-2 which has a close genetic similarity to bat coronaviruses and are thought to have been its likely origin. The virus primarily targets the respiratory system and causes flu-like symptoms upon exposure, although some patients may appear asymptomatic. In the early stages, the disease presents itself as a mild respiratory infection. However, as the disease progresses in severity, it may lead to acute respiratory failure, severe complications such as multiorgan failure, and ultimately death.

The wild tornado in the body: how the infection starts and kills

COVID-19 spreads in a similar way to cold and flu bugs; through droplets being left on surfaces after a person coughs or sneezes, which are then touched by other people and spread further. The Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 / CoVID-19) has been killing thousands of people every hour globally since it appeared. Clinicians and pathologists are still trying to fully understand how it inflicts such damage as it tears through the human body.

Although it well known that the lungs are ground zero (i.e. the main point of impact), the virus can extend to many other organs including the heart and blood vessels, kidneys, guts and brain. « Its ferocity is breathtaking and humbling », said Krumholz a cardiologist from Yale university.

The infection begins when an infected subject expels virus-laden droplets and another person inhales them, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus then enters the nose and throat and finds a comfortable home in the lining of the nose according to scientists from the Wellcome Sanger Institute. This region is lined with cell-surface receptor known as ACE2 (i.e. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) which are present throughout the body to help regulate blood pressure but it also marks tissues vulnerable to infection. The virus requires this receptor to enter a cell, and once inside it hijacks the cell’s machinery, multiplies itself and takes over new cells.

During the period where the virus is multiplying itself, an infected person may shed copious amounts of it, especially during the first week. There may not be any symptoms at this point, or the victim may develop a fever, dry cough, sore throat, loss of smell and taste, or head and body aches. If the immune system does not destroy the virus at this early stage, then it moves down the windpipe and starts to wreck havoc in the lungs where it can become deadly.

The thinner, distant branches of the lungs respiratory tree end in tiny air sacs called alveoli [alveolus (single)], each lined by a single layer of cells that are also rich in ACE2 receptors, the very same receptors that allows the virus to penetrate. When we are in good health, oxygen crosses the alveoli into the capillaries, which are tiny blood vessels that lie beside the air sacs (alveoli). That oxygen is then transported to the other regions of our body. But, when the immune system is stressed and fighting ardently against the virus, the battle disrupts the oxygen transfer. The front-line white blood cells release inflammatory molecules called chemokines, which in turn create more immune cells that target and destroy virus-infected cells. When these infected cells are destroyed by the chemokines, they leave a stew of fluid and dead cells – pus – behind. This process is the scenario that takes places in pneumonia and the corresponding symptoms are: coughing; fever; and fast, shallow breathing. In some cases, we find COVID-19 patients who recover, sometimes simply with oxygen breathed in through nasal prongs.

However, in other unfortunate scenarios, patients often deteriorate suddenly to develop a condition referred to as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), where they struggle to breathe as the oxygen levels in their blood falls abruptly. On x-rays and computed tomography scans, the lungs of these patients are shown to be riddled with white opacities where instead healthy dark space [i.e. air] should be. These cases end up on ventilators and many die. Autopsies have shown their alveoli (air sacs) stuffed with fluid, white blood cells, mucus and the detritus of destroyed lung cells.

Image: The cross section shows immune cells crowding an inflamed alveolus (air sac) whose walls break down during attack by the virus causing reduced oxygen intake – patients cough, experience rising fever and breathing becomes difficult / Source: Wadman (2020)

Some clinicians found that the driving force that leads to severely ill patients’ downhill trajectory and death to be a disastrous overreaction of their own body’s immune system, a reaction referred to as a « cytokine storm » , which viral infections are known to trigger. Cytokines are chemical signaling molecules that guide a healthy immune response, however, in a cytokine storm, the level of cytokines rise beyond the level of what is needed, and hence this excessive rush [i.e. storm] of immune cells also start to attack and destroy healthy tissues – these individuals’ blood vessels leak, blood pressure drops, blood clots form, and catastrophic organ failure can follow.

Some studies (Chen et al., 2020) have demonstrated elevated levels of these inflammation-inducing cytokines (Huang et al., 2020) in the blood of hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Jamie Garfield, a pulmonologist who treats COVID-19 patients at the Temple University Hospital argues that the real morbidity and mortality of this disease is probably driven by this out of proportion inflammatory response of the human immune system to the virus. However, other medical professionals are not convinced. “There seems to have been a quick move to associate COVID-19 with these hyperinflammatory states. I haven’t really seen convincing data that that is the case,” said Joseph Levitt, a pulmonary critical care physician at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Levitt is also worried that efforts to develop several drugs to dampen the cytokine response could actually cause harm by suppressing the immune response that our body needs to fight off the virus.

We find different views among the academic community on this new virus. Others are viewing it from a completely different perspective, and are focusing on the heart and blood vessels, that they believe is playing a significant role in the rapid deterioration of some patients.

Tearing the heart

All the classic symptoms of a heart attack was observed in a 53-year-old Italian woman in Brescia along with signs in her electrocardiogram and high levels of blood marker suggesting damaged cardiac muscles. Further tests revealed cardiac swelling and scarring, and a left-ventricle – which is usually the powerhouse chamber of a human heart – so weak that only one-third of the normal amount of blood could be pumped. When doctors injected dye in her coronary arteries to look for what they believed to be a blockage that is usually associated with heart attacks, they found nothing. The next test carried out revealed that the culprit was in fact COVID-19.

It is still a mystery to academics how the virus attacks the heart and blood vessels but many preprints and scientific papers attest that such damage is common. A JAMA cardiology paper observed damages to the heart in nearly 20% of COVID-19 patients (Shi et al., 2020) out of 416 hospitalised patients in Wuhan, China. Another Wuhan study revealed that 44% of 36 patients admitted in ICU had arrhythmias, i.e. irregular heart beats (Wang et al., 2020).

What has been discovered, is that the disruption extends to blood itself. Among 184 COVID-19 patients in a Dutch ICU, 38% had blood that clotted abnormally, and about one-third already had clots (Klok et al., 2020). Blood clots are very dangerous since they can break apart and end up landing in the lungs, blocking vital arteries – a condition known as pulmonary embolism, which has killed many COVID-19 patients. Blood clots from arteries can also end up in the brain, causing stroke. Many COVID-19 patients have dramatically high levels of D-dimer, a byproduct of blood clots. Hence, it is very likely that blood clots have a major role in the disease severity and mortality with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Infection may also lead to the constriction of blood vessels. There are reports emerging of ischemia [i.e. an inadequate blood supply to an organ or part of the body, especially the heart muscles] in the fingers and toes – reduction in blood flow can cause swollen, painful digits and eventually tissue death. Blood vessels carry oxygen to various parts of our body, and when they become constricted problems will logically arise. In the lungs, the constriction of blood vessels may explain the reports of a very perplexing phenomenon seen in patients with pneumonia caused by COVID-19: some patients although having extremely low blood-oxygen levels are not gasping for breath. Since we are still uncovering the depths of the virus, one explanation may be that at some stages of the disease, the virus modifies the delicate balance of hormones that regulate blood pressure and constricts the blood vessels going to the lungs. Logically, constricted blood vessels will lead to oxygen uptake being impeded – this may be the cause of low blood-oxygen levels rather than clogged alveoli (air sacks) as explained above.

It is very important to take note that if COVID-19 targets blood vessels, it may explain why patients with pre-existing damage to those vessels, such as those with diabetes and high blood pressure, face a higher risk of serious disease. The recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on hospitalised patients in 14 US states found that bout one-third had chronic lung disease and nearly as many had diabetes and half had pre-existing high blood pressure (Garg et al., 2020). It has also been observed that there is a very low number of cases suffering from asthma and other respiratory diseases. The risk factors seem to be vascular: diabetes, obesity, age and hypertension. Academics are still in the dark regarding the causes of cardiovascular damage. Since the lining of the heart and blood vessels are rich in ACE2 receptors just like in the nose and the alveoli, it is possible that the virus may be directly targeting and attacking them. Another possibility for cardiovascular damage could be the lack of oxygen caused by a combination of factors: lack of oxygen, chaos in the lungs and damages to blood vessels. A cytokine storm unleashed by the immune system itself could also be responsible for damages to the heart as it does for other organs.

Destruction in multiple zones

While there is worldwide tension regarding the shortage of ventilators for failing lungs, less attention has been given to dialysis machines. Jennifer Frontera, a neurologist from New York University’s Langone Medical Center who has treated thousands of COVID-19 patients pointed out that if patients are not dying from lung failure, they are dying from renal failure. Hence, her hospital is developing dialysis protocols with different machines to support additional patients. As usual, the ACE2 receptors, a favoured penetrating site for the virus, is abundantly present in kidneys. Going by a preprint, 27% of 85 hospitalised patients in Wuhan had kidney failure (Li et al., 2020). Another report read 59% of nearly 200 hospitalised COVID-19 patients in China’s Hubei and Sichuan provinces had protein in their urine (Diao et al., 2020), and 44% had blood clot; both suggest that kidney damage took place. Patients with acute kidney injury (AKI), were more than five times as likely to die as COVID-19 patients without it, the same Chinese preprint reported.

“The lung is the primary battle zone. But a fraction of the virus possibly attacks the kidney. And as on the real battlefield, if two places are being attacked at the same time, each place gets worse,” says Hongbo Jia, a neuroscientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’s Suzhou Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Technology and a co-author of that study.

The electron micrographs from the autopsies of kidneys revealed viral particles (Diao et al., 2020), suggesting a direct viral attack. However, the kidney injury may also be a collateral damage caused by ventilators – that heighten the risk of kidney damage – as do some antiviral compounds such as remdesivir [which has been used experimentally in early COVID-19 patients]. The immune system’s cytokine storms may also severely reduce blood flow to the kidney and often causing fatal damage. Diabetes can also increase the chances of kidney injury. Hence people with chronic kidney diseases are at a higher risk for acute kidney injury.

Combo hits to the brain

Another range of symptoms in COVID-19 patients focus on the brain and the central nervous systems (Mao et al., 2020). Frontera says that neurologists are required to assess 5% to 10% of coronavirus patients at her hospital and believes that it may be a gross underestimate of the number of patients whose brains are struggling since many are sedated and on ventilators. Patients have suffered from brain inflammation, encephalitis (Moriguchi et al., 2020), with seizures and with a sympathetic storm [i.e. a hyper reaction of the sympathetic nervous system that causes seizure-like symptoms and is mostly observed after a traumatic brain injury]. Some COVID-19 patients even lose consciousness for a short amount of time while others suffer strokes. The loss of the sense of smell has also been widely reported. Frontera and others are asking themselves whether in some cases, infection depresses the brain stem reflex that senses oxygen starvation; this may provide an explanation to why despite dangerously low blood oxygen levels, patients are not gasping for air.

The former coronavirus behind the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic – a cousin of COVID-19 – could infiltrate neurons and at times caused encephalitis. Since ACE2 receptors are present in the neural cortex and brain stem, the virus could interact with those receptors and penetrate the brain. In a case study in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, a team of academics from Japan found traces of COVID-19 traces in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient who developed meningitis and encephalitis, insinuating that COVID-19 can penetrate the central nervous system.

Image: Tissue damage in the brain (milky white areas shown by the arrows) as a result of encephalitis developed by a 58-year-old woman infected with COVID-19 / Source: (Poyiadji et al., 2020)

However, other factors could also be damaging the brain, such as a cytokine storm triggered by patients’ immune system itself, leading to swelling, and the blood’s exaggerated tendency to clot could trigger strokes. The collection of neurological data from care patients received is ongoing at a worldwide consortium that now include 50 centers in order to identify the prevalence of neurological complications in hospitalised COVID-19 patients and document how they fare.

The aim of course is to better understand the virus’ impact on the nervous system, including the brain. Sherry Chou, a neurologist speculates about an invasion route for the virus: through the nose, then upward through the olfactory bulb which connects to the brain, which may explain the loss of smell.

To the gut

Diarrhea with blood, vomiting and abdominal pain was reported in early March 2020 from a 71-year-old woman from Michigan who returned from a Nile river cruise. Doctors suspected the common stomach bug, e.g. Salmonella. However, after she developed a cough, nasal swabs revealed that she was positive for COVID-19. Gastrointestinal (GI) infection was diagnosed after a stool sample was positive for viral RNA and an endoscopy revealed signs of colon injury according to a paper in The American Journal of Gastroenterology (AJG) (Click to see).

This case adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that like the SARS, COVID-19 can infect the lining of the lower digestive tract where, once again, the ACE2 receptors needed for the virus to enter are abundant. As many as 53% of sampled patients’ stool samples have shown to contain viral RNA. The virus’ protein shell was also found in gastric, duodenal and rectal cells in biopsies by a Chinese team who reported it in a paper in Gastroenterology (Xiao et al., 2020). “I think it probably does replicate in the gastrointestinal tract,” said Mary Estes, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine.

Up to 50% of patients, making up about 20% across studies experience diarrhea. Gastrointestinal Infection (GI) however is not on the CDC’s list of COVID-19 symptoms which could lead to some COVID-19 cases to go undetected. The co-editor of Gastroenterology, Douglas Corley of Kaiser Permanente, Northern California said: “If you mainly have fever and diarrhea, you won’t be tested for COVID.”

So, can COVID-19 be passed on through feces? We do not know if the stool contains active, intact, infectious virus or simply RNA and proteins, there is no evidence to date. Based on experiments with SARS and with the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome, a cousin of COVID-19, the risk from fecal transmission is probably low.

Finally, the virus also affects the eyes as one-third of hospitalised patients develop conjunctivitis – reddish, watery eyes – although it is not clear if the virus directly attacks the eyes (Wu et al., 2020). Some other reports have also suggested liver damage since more than 50% of COVID-19 (Zhang, Shi and Wang, 2020) patients hospitalised in two Chinese centers had elevated levels of enzymes (Fan et al., 2020) which suggest injury to the liver or bile ducts. However, many experts reportedly told Science that direct viral hits are unlikely, stating that other events in a failing body, like drugs or an immune system overdrive, are more likely driving the liver damage.

COVID-19 is a new virus and the academic community are only beginning to uncover its secrets and find answers to these questions:

Who is most vulnerable?

Why does it develop so rapidly and why it is so hard for some patients to recover?

Why does the infection spread so rapidly from people who are asymptomatic?

Why some patients are hardly affected while others are hit so severely?

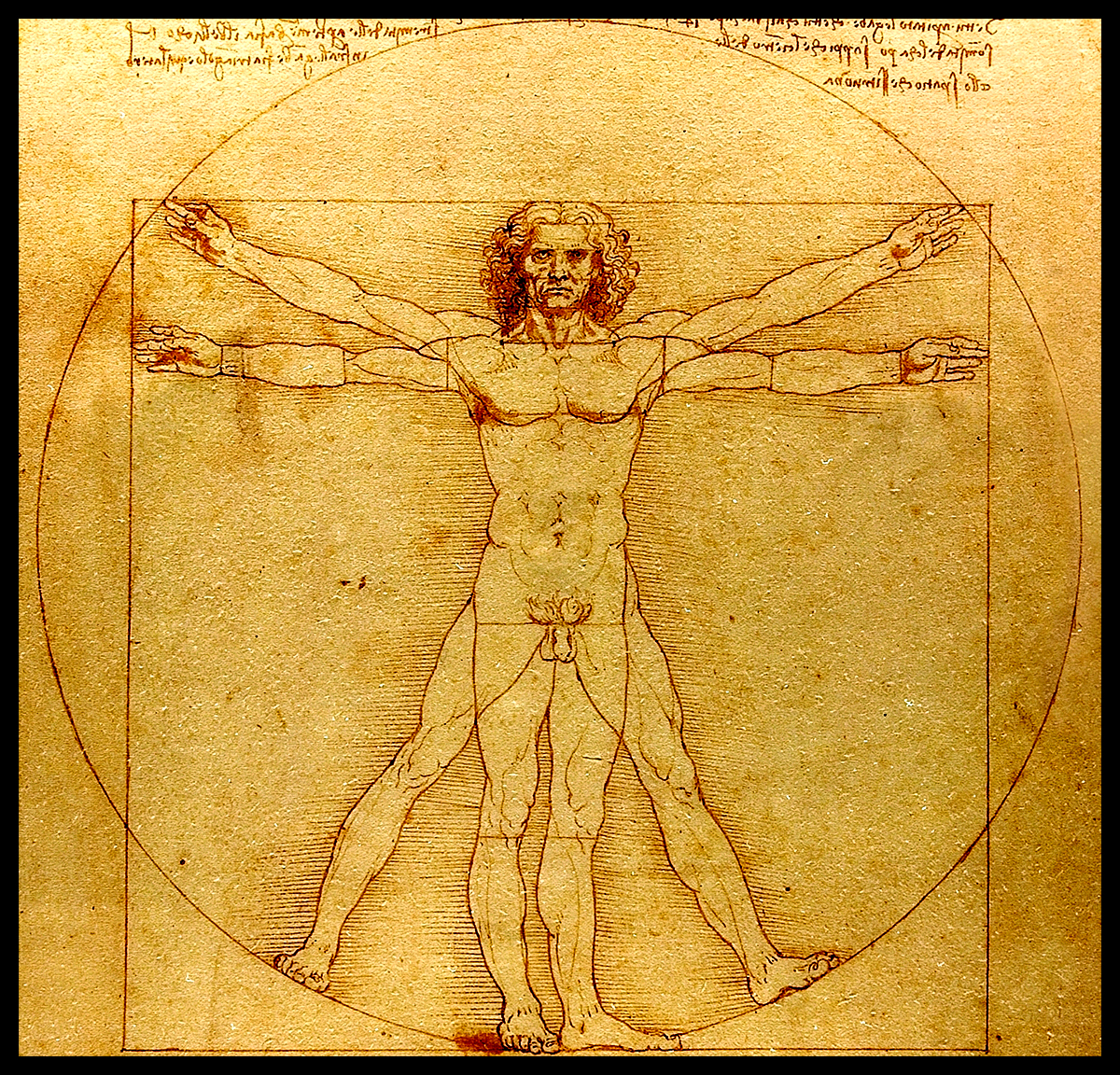

The answers to those questions lie in the depths of our immune system. In the human body, immune cells are microscopic warriors that fight off invasive viruses in our body and we have 2 trillion of those. When viruses enter our body, immune cells instantly track them and devour the enemy, injecting toxins to destroy them and sometimes even release a sticky web to ensnare them.

Latest scientific discoveries are beginning to uncover the enigmatic mechanism behind our immunity. We are now confident that the novel coronavirus has the ability to break down our immune defences with its formidable powers; COVID-19 slips through, suppresses and unleashes chaos. Research on the human immune system is continuing and is helping to find potential new treatments to fight off the novel coronavirus. As vaccines were being developed, scientific research revealed that blood from recovered COVID-19 patients can save the lives of those suffering from severe symptoms.

The COVID-19 virus spreads from tiny droplets released from an infected person’s mouth, and these are smaller than a 1000th of a millimeter in diameter; a droplet around 1mm across can contain as much as 7 million virus particles.

Image: This next-generation microscope enables the observation of living cells at work, capturing cells in attack mode in 3D.

Nowadays, advanced technology has provided powerful microscopes that enable us to visualise the world within our bodies; we can even observe living cells at work and capture immune cells in attack mode in 3D. Other tools such as ultra-high 8K resolution microscopy, 3D reconstructions of electron microscope images, as well as the latest CGI techniques enable us to see the wars between viruses and the cells of our body.

The virus, SARS-CoV-2, belongs to a group of coronaviruses (CoVs) of the Coronaviridae family, namely, the β-CoVs, which infect mammals. Coronaviruses are pleomorphic enveloped particles with a single-stranded RNA genome. There are fringe projections known as spike (S) proteins on the virus’s surface, which are the main characteristic of these viruses. The virus uses the S protein to enter the host cell by interacting with the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The viral RNA is released in the host cells and triggers a cascade of events that replicate viral RNA and synthesize structural and non-structural proteins. These proteins are vital in the survival and propagation of the virus.

SARS-CoV-2 is mainly transmitted from human to human via respiratory droplets. When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, another person could be infected if the droplets are inhaled or come into contact with their mucous membranes. The novel coronavirus gets into the body through droplets that carry the virus [e.g. through the mouth, or nose]. However, the virus cannot keep going, and the first barrier it meets is the respiratory tract – the airway that leads into our lungs. The image below shows the repiratory tract magnified more than 10,000 times by an electron microscope.

Image: Human respiratory tract magnified 10,000 times showing tiny hair-like structures called cilia [about a 100th of a strand of human hair] that make tiny rapid movements [over 1000 times per minute]. These movements cause foreign matter such as viruses to be pushed away. However, COVID-19 can infect cilia cells by stopping their sweeping movements in order to slip through and penetrate deep into the lungs.

The novel coronavirus has the potential to infect cilia cells by stopping their protective sweeping movements and slip through into the airways to finally work its way deep into the lungs. When that happens, the COVID-19 infection begins; the virus particules approaches a lung cell and targets an odd looking protrusion on the lung cell’s surface which is only about 1/100000 mm. The novel coronavirus attaches its spike onto that protrusion on the cell surface, then the COVID-19 virus gradually sinks itself into the cell – the infection is now complete! This method is a cunning trick unique to viruses.

Animation: The novel coronavirus attaches its spike to the protrusion on the lung cell’s surface and burries itself into that cell to infect it.

The protrusions [shown in purple in the above animation] which are present on the surface of lung cells, act as a keyhole, only allowing essential substance such as cholesterol. Hence, only substances with the right “key” are allowed to enter the cell. The COVID-19 virus has a fake key that fits perfectly with the keyhole of the cells. So, COVID-19 tricks the lung cell into allowing an intruder inside. The image below was taken with an electron microscope; it shows the interior of a cell that has been infected by COVID-19 [all the red dots are COVID-19 virus particles].

Image: Interior of a cell infected by COVID-19. All red dots are virus particles that once inside can replicate itself as much as a 1000 times before breaking out.

Image: Microscopic image showing the moment where COVID-19 particles [in red] have burst out of an infected cell. Vast amounts of viral particles scatter all around, looking for new cells to infect.

When the COVID-19 burst out and scatter all around from an infected cell while continuing the infection process, patients tend to suffer from more severe pneumonia.

In X-rays of COVID-19 patients, the areas that are inflamed due to the viral infection show up as white spots while the lungs are shown in black; and when the pneumonia intensifies and becomes critical, X-rays show vast amounts of white areas [i.e. vast areas affected by inflammation].

Image: X-ray image of a COVID-19 infected patient. Lungs are shown in black and areas of inflammation caused by the viral infection are shown in white [as these spread, pneumonia symptoms worsen]

In order to prevent such crisis, our body relies on immune cells, which are the defence unit of the human organism. A cell infected with COVID-19 starts to release large amounts of blue particles, a substance called interfera, which sends a warning to immune cells [i.e. our defence units] in order to alert them of a dangerous enemy; this alert [i.e. blue particles] is carried across the body through the bloodstream. Those alert messages are then received by round cells that roam in our blood vessels, known as phagocytes.

Animation: The inside of a blood vessel showing phagocytes on patrol inside these blood vessels all around our body. When they receive the alert message [i.e. blue particles released by infected cells (interferons)] warning them of an enemy intrusion, they head out from the blood vessel to the site of infection

When phagocytes locate their target, i.e. foreign matter such as viruses, they move in and devour it whole, even if those targets happen to be larger than themelves. Patients infected with COVID-19 but who do not show any symptoms are thought to have incredibly active phagocytes in their bodies; those powerful defensive units which engulf the viral enemy are known as our innate immunity and it is part of a system that we have inherited since birth; it derives from our shared evolutionary history of encouters with viruses as human beings.

Animation: Phagocyte devouring the viral target which is larger than itself

But why unlike others, do some people experience life threatening symptoms as their health deteriorates even though they are supposed to be protected by our innate immunity?

Latest research has revealed an intriguing possibility; the COVID-19 virus may have developed the ability to evade the defensive attacks of our innate immune system. This was uncovered by Dr. Kei Sato at the Tokyo University Medical Research Institute as the genetic information stored inside the COVID-19 virus was explored.

Image: ORF3b, the unique gene of the COVID-19 virus that gives it the ability to deceive the innate immunity of human beings. “The poor IFN responses in COVID-19 patients may be explained by the action of this viral product, ORF3b”, said the lead scientist, Kei Sato

When this genetic information was compared to those of other viruses, the COVID-19 virus was found to have a unique gene [ORF3b, as shown in the image above]. Further experiments revealed that the function of the unique gene discovered was to give the COVID-19 virus the ability to deceive our innate immunity.

Remember, as explained above, a COVID-19 infected cell will release masses of alert messages [i.e. blue particles known as interferons] to warn our immune cells about the presence of a viral enemy. However, when this unique gene [ORF3b] discovered in the COVID-19 virus is activated, those defensive alerts to our immune cells are supressed; only about 1/10 of those warnings are sent [90% blocked] from the infected cell.

Animation: When the unique ORF3b gene that is present in the COVID-19 virus is activated, it drastically reduces the amount of interferons (blue particles) sent by the infected cell [in dark red] to warn the immune cells to take action.

So, when this happens, the phagocytes do not receive any message of the impending danger and hence they cannot be mobilized to neutralise the COVID-19 virus, which is left to replicate itself at will. A further study has found that without the warning messages of the interferons to the phagocytes, the COVID-19 virus can replicate by as many as 10,000 times in only 2 days.

Image: The ability of the COVID-10 virus to replicate and cause severe symptoms is largely related to the patient’s ability to release interferons. Left (with interferons); Right (without interferons); Virus particles replicating itself (in Red)

Now we know that people who experience severe symptoms produce lower levels of interferons, and it is very likely that this weakness in some people allows the novel coronavirus to spread throughout the body and replicate itself savagely, resulting in severe and life-threatening symptoms.

Graph: The number of interferons produced are clearly poor in patients with severe symptoms (Konno et al., 2020)

So, supressing our body’s red alerts is one deadly weapon COVID-19 is using against us and this may be the reason why it has turned into such a global crisis and emergency. Countries around the world and their governments have been stunned by this pandemic and have been taking desperate measures such as complete lockdowns at the cost of their economy in a bid to halt this the spread of this ugly infection.

One of the greatest difficulties with COVID-19 is that there is a certain delay before any convincing symptoms appear and if people are unaware that they are infected, they eventually go on to infect others. Usually, when our body is infected by a virus, an alert substance is released within our bodies, which causes our body temperature to rise in order to activate the immune response. However, since the novel coronavirus is suppressing those warning signals, infected people show no signs such as fever, even thought the viral load within their bodies keeps increasing. That superficially asymptomatic state leads to people not knowing that they are infected and hence allows the virus to spread since those infectious hosts are going unchecked.

Another worrying news is that the virus’s ability to suppress those warning signals seems to be getting stronger with different genetic types of COVID-19 variants spreading throughout the planet. A strain found in Ecuador has a slight alteration in the gene that suppresses the alarm substance. Dr. Paul Cardenas who has been studying patients at the hospital in the capital of Quito said that it is abnormal to find young people developing severe symptoms that quickly. After virus samples of the new strain was collected and analysed, the gene that suppresses alarm signals (i.e. interferons) revealed a mutation; that change leads to the amount of interferons being reduced even further to 1/20. If this powerful variant continues to spread, the immune system’s defence will be forced to fight even tougher battles against the coronavirus.

We have also recently heard a lot about the B.1.1.7 variant [first detected in the UK], the B.1.351 variant [first detected in South Africa] and P.1 variant [detected in Manaus, Brazil]. Other variants continue to appear, such as the one in New York, named B.1.526 which contains the same E484K mutation that has caused so much concern in the UK’s B.1.351 (South Africa) variant; which allows the virus to escape some of the body’s immune response. There are many other variants of COVID-19 appearing around the planet due to genetic changes and these changes will lead to even more variants that could eventually become resistant to the vaccines developed and drugs used to treat patients with severe symptoms.

Vaccines may also have to be updated and modified to address the new variants since those developed for the original virus have been found to be less effective against the B.1.351 (South Africa) variant. The latter variant has been reported to be on the rise in the UK and patients affected by it were on average older and more frequently hospitalised. As for the B.1.526 (New York) variant, it appears to be scattered in the northeast of the US, and its unique set of spike mutations may also pose an antigenic challenge for current interventions. In Finland, The Fin-796H variant, identified by researchers from Vita laboratories and the Institute of Biotechnology at the University of Helsinki, is reported to have mutations similar to those seen in B.1.1.7 (UK) and B.1.351 (South Africa).

The B.1.1.7 variant identified in early October 2020 from genomic sequencing of samples from COVID-19 carriers in the south east of England has been classified as a variant of concern (VOC-202012/1). In December this variant spread from the south east to London and the rest of the UK and its growth coincided with the second national lockdown (5 November to 2 December 2020). Additional control measures had to be imposed after its increased rate of spread with international restrictions on travel from the UK shortly following, in particular to France and to the rest of Europe late in December 2020 to curb the contamination of other countries with this new variant, despite evidence that it had already been present outside the UK. Since then, the prevalence of B.1.1.7 (VOC-202012/01) has been increasing in both Europe and the US. Research conducted in the UK measured the possibility of death within 28 of the 1st positive test result and found that the risk of mortality with the B.1.1.7 (VOC-202012/01) variant is inreased and is high. Hence, as the research carried out by Robert Challen and his colleagues suggest in the British Medical Journal, the UK variant has the potential to raise the mortality rate significantly compared with previously circulating variants, and healthcare capacity planning and national and international control policies are all impacted by this finding as increased mortality lends weight to the argument that further coordinated and stringent measures are justified to reduce human deaths from COVID-19 (Challen et al., 2021).

As of the 30th of March 2021 in France, as predicted by epidemiologists and infectiologists , the UK variant B.1.1.7 identified as “anglais” by the French, has been found to be responsible for the majority of contaminations. Of the COVID-19 positive PCR tests screened to differentiate the original SARS-CoV-2 strain from a variant, 79% of the infections in France were found to be due to the much more contagious “English” mutant B.1.1.7. The share of the South African and Brazilian variants remains is still quite small as the chart below shows.

Pink – UK Variant; Blue – SA Variant; Yellow – Unidentified Variant, and Grey – Original Wuhan Strain / Représentation des variants dans les tests PCR criblés. Source: Geodes, Santé publique France

If the COVID-19 virus manages to evade our innate immune system and keeps on multiplying, in most cases hosts (i.e. humans) remain asymptomatic for around 5 days after they are infected. But when the viral load in the body exceeds a certain limit, symptoms begin to appear in the shape of fever, cough and fatigue. As the virus breaks down our innate immunity and escapes our defences, it continues to replicate at will.

However, the immune system will not just give up. This is when our secondary defence force takes action; it is known as our “Adaptive Immune System” and that is deployed in the fight against the infectious viral invader. This scenario is still dependent on the phagocytes that had been fighting the virus, however now the phagocytes move to a different location and start to act as messengers seeking reinforcements. That messenger phagocyte will attach itself to a blue immune cell while holding a fragment of the novel coronavirus that it had devoured earlier in what looks like a clasp. The blue immune cell will accept this fragment from the clasp and process it as an enemy intel, and will then become activated – it is now a killer T cell ready to attack.

Animation: The messenger phagocyte attaches itself to a blue immune cell while holding a fragment of the novel coronavirus that it had devoured earlier in what looks like a clasp [shown in golden yellow]. The blue immune cell accepts that fragment from the clasp and processes it as an enemy intel, and becomes activated – it is now a killer T cell [shown in green]ready to attack.

These activated killer T cell with information about the virus will now target cells which are infected with the novel coronavirus – it knows what it is looking for. Infected cells have fragments of the COVID-19 virus protruding from its surfaces. The killer T cell will move in and compare those protruding fragments with the information they received from the messenger phagocyte, and if the target matches, it will be confirmed and the killer T cell will will commence their attack; the virus as well as the cell will then be completely obliterated.

Animation: The Killer T cell attaches itself to the surface of the infected cell, compares the fragment in the protruding clasp on the surface with the information it received from the messenger phagocyte and launches its devastating attack once the target is confirmed – obliterating both virus and cell.

Video: We can see the live action from a cutting-edge microscope that has caught the moment of attack by a killer T cell [in green] once it attaches itself to its target cell [in blue]; a toxic substance [in red] is injected, destroying the infected cell along with the alien virus inside.

Unfortunately, it now also appears that the novel coronavirus is finding ways to evade the killer T cell attack. Recent findings from China suggest that the COVID-19 virus has a unique quality setting it apart from other viruses. The novel coronavirus is now targeting those protruding clasps [that hold viral fragments] on the surface of the cells it has infected, reducing their numbers by 60%.

Animation: COVID-19 virus breaking down the clasps protruding from the surface of infected cells, making it much harder for killer T cells to locate them, and allowing the virus to continue multiplying unchecked.

That makes it much harder for the killer T cells to locate infected cells, hence, the infection remains unchecked and the virus continues to multiply in the hosts.

But this war is far from over, since in retaliation our immune system sends out another unit known as the B cells. B cells also get their enemy intel from viral fragments just like killer T cells, however they produce powerful projectile weapons.

Animation: B cells receiving information about the viral target from the phagocyte, and releasing the appropriate antibodies (in Yellow)

B cells release small yellow particles and are shaped as the letter Y when viewed through a microscope; these amazing yellow particles are known as antibodies. These yellow projectile weapons released from B cells close in on the ugly COVID-19 virus and bind to the spikes on its surface [remember these spikes are the fake keys that the virus uses to invade human cells]. Once the virus’s surface is covered with those yellow antibodies, the virus is rendered uselss as it can no longer attach to cells, infect them or replicate. With nowhere to go and hide, they are devoured one by one by the phagocytes. When infected patients reach this stage, they are out of danger, since their bodies will now begin to recover slowly.

Animation: Yellow Y-shaped antibodies produced by the B cells close in on the virus and bind to its spikes. Covered with those amazing antibodies the virus can no longer bind to cells, infect or replicate. With nowhere to go, they are devoured by phagocytes.

Yet, the work of T cells and B cells are far from over, since these amazing defence units will retain their memories of the viral enemy and remain alert in our bodies and ready to fight back for future attacks. These special units study the viral enemy, launch intensive attacks and even after repelling the virus, they will remain vigilant to protect our bodies from harm – it is our adaptive immune system in action.

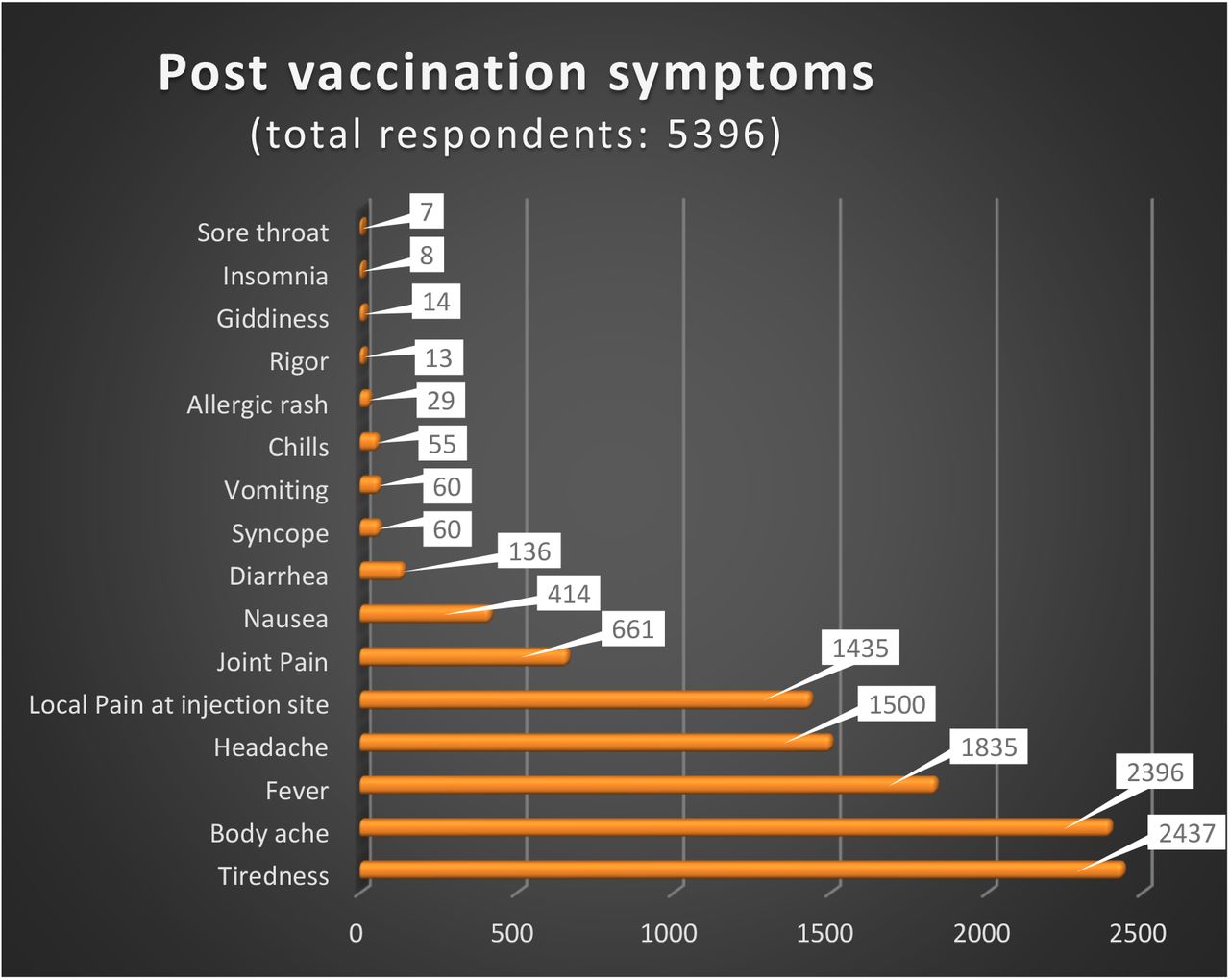

Vaccines developed against COVID-19 attempt to enhance the power and effectiveness of our adaptive immune system by injecting fragments from an attenuated virus into the body so that information about the novel coronavirus can be passed on safely to T cells and B cells; in that way our adaptive immune system will learn about the enemy before any infection occurs and be ready to provide the necessary attack if infected.

Two studies available as preprints conducted in England found that middle aged women face higher risk of debilitating ongoing symptoms, such as fatigue, breathlessness, muscle pain, anxiety, depression, and “brain fog” after hospital treatment for COVID-19. 7 in 10 patients admitted experiencing “long covid” symptoms an average of 5 months after discharge and those symptoms were more prevalent among women aged 40-60.

Figure: Prevalence of medical conditions for males & females aged 40 to 60 [Change between 1991 to 1993 and 2011 to 2013 in England / Source: GOV.UK Public Health England

The study carried out in England is reported in the British Medical Journal, it found that among those who classify themselves ethnically as “White”, with 2 or more comorbidities at admission, and receiving invasive ventilation while in hospital the risk was increased; however the severity of acute COVID-19 disease did not affect the likelihood of experiencing long COVID symptoms. [Note: Ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups such as a common set of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area(s). Ethnicity is sometimes used interchangeably with the term nation]

From the 1077 patients studied, only 29% felt fully recovered when followed up, on average 5 months after discharge. More than 1/4 had clinically significant symtoms of anxiety and depression, 12% had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, 17% had at least mild cognitive impairment, 46% had lower physical performance than age and sex matched controls, and 20% had a new disability. Before being admitted to hospital for treatment, 68% had full time work, but 18% of those had not returned to work and 19% had had to change their working habits due to long-lasting effects. The patients were grouped into 4 clusters by researchers, according to the severity of their physical and mental symptoms post-COVID: Very Severe (17% of patients); Severe (21%); Moderate with Cognitive Impairment (17%) and Mild (46%)

Rachael Evans, a clinical scientist and reseacher from the National Institute of Health Research declared: “The symptoms are very real, but they don’t have a straightforward relationship with heart and lung damage, or certainly heart and lung damage can’t explain all the symptoms.”

A smaller second study, from the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium (ISARIC), found that women under 50 were 5 times less likely to report feeling recovered, 2 times as likely to report worse fatigue, 7 times more likely to become more breathless, and more likely to have greater disability than men of the same age who had been admitted to hospital with COVID-19. Disability usually affected memory, mobility, communication, vision, or hearing. More than half of the 327 patients assessed did not report feeling fully recovered when followed up on average 7 months later, and persistent symptoms were reported by 93.3%, with fatigue and breathlessness the most common.

Chris Brightling, a professor of respiratory medicine at the University of Leicester and a study researcher, speculated that sex based differences in the immune response may be responsible for the higher prevalence of long COVID symptoms in women, noting that autoimmune diseases were more prevalent in women than in men aged 40-60.

“Maybe there’s a difference in the immune response acutely, such that men are more likely to have a more severe condition at the time of the infection,” he told a press conference at the Science Media Centre on 24 March 2021. “It may be that the immune response is different in women, so you then have a continued inflammatory reaction that then leads to a higher likelihood of having long covid.”

Higher levels of C reactive protein, a marker of systemic inflammation were found in patients with the most severe long COVID symptoms. Brightling said that a number of immune and chronic inflammatory condition can also cause elevated C reactive protein. About 450,000 COVID-19 patients have been admitted to hospital in the UK, so a “very large” proportion of these would potentially be affected by long covid, Chris Brightling said, adding, “Clearly there’s an even larger number of people that have had covid in the community, and a portion of those will also have long covid.” (Evans et al., 2021; Sigfrid et al., 2021)

Image: La préparation d’une dose de vaccin. | Photo: Quemener Yves-Marie

Researchers and health departments are working as fast as they can to ensure the safety of treatments and maximise the effectiveness of vaccines. While vaccine campaigns have begun across the planet, many people have lost their lives since the COVID-19 virus appeared in late 2019 and many others are still being infected.

But, what may have happened in the bodies of patients who became critical and ultimately lost their lives?

Image: Casket manufacturing business, South Brooklyn Casket Co. in the U.S, sending a casket to a customer during the COVID-19 pandemic

More than 150 autopsies have been conducted at the University Medical Center Hamburgg-Eppendorf in Germany and something quite unusual was discovered in the lungs of those COVID-19 victims.

Dominic Wichmann: “From our past studies where we learned that with every new disease there are new findings when you do autopsy on a regular basis. We thought it might be very interesting from a scientific point of view to get more into detail in COVID-19. We were really really surprised about very very high incidents of venous thromboembolisms and pulmonary embolisms. We discover that within the first 12 patients, we had about one third of patients who died from pulmonary embolism (Wichmann et al., 2020).”

Pulmonary embolism is a disease where blood clots form in the lungs. Blood clots cause blood circulation to fail in the human body and the resulting lack of oxygen led to the death of those patients. A closer look showed many blue dots among the red clots of blood in those patients; those blue dots are the dead remains of a type of phagocyte called neutrophils that had caused the clots.

Video: Blue dots, which are the dead remains of neutrophils (a type of phagocyte) were found within the blood clots in the lungs of deceased COVID-19 patients

As already explained above clotting occurs when our immune system goes into overdrive, a phenomenon called a cytokine storm. To explain this phenomenon, it is important to understand that the immune cells in our bodies can become overly activated when faced with a virus that is replicating in huge numbers. It has long been suspected that the human body’s own hyperactive immune cells have been damaging the blood vessels, and in order to close those internal wounds, platelets in the blood come would come together to form clots; those grow larger and sometimes end up blocking circulation. The important point to note is that recent research has shed light on this very disturbing mechanism where cytokine storms trigger dangerous blood clot formation.

Yogen Kanthi from the University of Michigan explained: “When Neutrophils start to detect that there are pathogens circulating in the bloodstream, they will start to take their DNA inside of the cell and they expel it outside of the cell. They spit it out from something called a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET). We know that certain cytokines that are released in the setting of COVID-19 can prime the neutrophil and make the neutophil more likely to form NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Trap).“

What we need to understand is that NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) are essentially suicide attacks, and this phenomenon was only recently discovered by the academic community in 2004. In normal cases, those kinds of attack will not cause any clotting. But in a cytokine storm overly active phagocytes in our bloodstream self-detonate in excessive numbers – that is where the danger of clotting appears.

Image: The moment of attack: the yellowish-orange phagocyte shown here is only a 100th of a millimeter wide and here it is captured as it self-detonates, hurling its contents (in green) towards the enemy virus (in red). This green weblike structure is the DNA of the phagocyte; the cell sacrifices itself by detonating in a desperate effort to trap the enemy harming the body with its DNA’s sticky texture. (Image courtesy: Max Planck Institute, Germany)

Video: A phagocyte self-detonating and releasing its DNA (in orange), seen here bursting out of that cell. In normal cases, those kinds of protective and self-sacrificing attacks will not cause any clotting. But in a cytokine storm overly active phagocytes in our bloodstream self-detonate in excessive numbers – that is where the dangerous blood clot formation begins

When excessive numbers of DNA NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) have been cast from the excessive number of phagocytes sacrificing themselves by self-detonating, those can even scatter blood components in the vicinity, lumps from those blood components form clots and bind to each other to grow larger and larger, to the point where they have the potential to completely block blood vessels in the human body. So, despite the intention of the phagocyte to protect its organism, these extreme suicide attacks backfire by forming blood clots that lead to death.

Video: Clots being formed by scattered blood components [formed due to the excessive self-detonations of phagocytes] in the vicinity, binding together and eventually blocking blood vessels

Yogen Kanthi further explains: “COVID-19 as you know, is caused by the SARS-2 coronavirus. And this is a normal virus that our bodies have not encountered before. As a result of that, the bodies don’t know how to respond to it. And so they are pulling out every tool that we have in the toolbox to try and fight this infection. What this means is the infection results in unregulated amounts of inflammation. And so inflammation can be very helpful in the beginning to try and fight off infection and help to repair organs. But if the inflammation is unregulated and continues at high levels for long periods of time that inflammation can be damaging to the body.”

Autopsies carried out on victims of COVID-19 have revealed that blood clots were the direct cause of death for 1/3 of those who lost their lives (Wichmann et al., 2020). Hence, to prevent the formation of deadly blot clots deriving from cytokine storms [i.e. the excessive self-detonations of phagocytes], those cytokine storms must be supressed. This is why drugs to dampen the reactivity of the human immune system have been trialed and considered as potential life-saving treatments in the fight against COVID-19. We are now armed with a new strategy, and hope is on the horizon to help patients with the severest symptoms.

Understanding the Immune System: the legacy of the shared evolutionary history of human primates on planet Earth

In the fight against viruses and pathogens since the dawn of mankind on our tiny blue planet, our immune system has always been the ultimate weapon and its presence can be traced way back in the shared evolutionary history of life. About 550 million years ago, the Cambrian explosion lead to the creation of the wide range of living organisms.

Viruses also existed at that time and are believed to have had spikes on their surfaces; those spikes are the fake keys modern viruses use to infect their hosts. Our evolutionary kin back then looked like a fish, since all life came from water.

Those incredible cells from our adaptive immune system such as T cells and B cells appeared as they endured viral attacks through the course of their evolution with the ability to remember the enemies they encountered and the protective and defensive strategies they used against viruses.

Even if the COVID-19 virus continues to cause panic worldwide, studies have shown that viruses and their hosts have not always been antagonistic towards each other in the course of the evolution of human life on Earth. There are occasions when those viruses and their hosts co-existed, mutually taking advantage of one another. Hence, some viruses are known to have embedded their genes into the DNA of our cells that they had infected. Our early ancestors have also been faced with viruses and were infected by many that permanently left their mark in our DNA; this is a fact of our shared evolutionary history as human primates on planet Earth. As much as 8% of the human genome comes from viruses; and our bodies may have taken advantage of the qualities of those viral genes in its own evolution to gain various important functions.

The process of creating new life itself testifies as a great example. In the process of fertilisation where the sperm binds to an egg, the sperm carrying the father’s DNA has to enter the mother’s egg. Since the egg views the sperm as a foreign substance, the sperm has to use a key to gain entry into the egg. This process is remarkably similar to how a virus enters a cell [as already explained above]. Modern academics and researchers believe that this process comes from the evolutionary past of life on earth; the fertilisation process may have taken advantage of the techniques of viral genes that had infected our early ancestors thousands of years ago.

There are also other functions about humans that are thought to have evolved from viral genes picked up along the way throughout the our shared evolutionary history, such as the placenta, which enables babies inside the womb to receive nutrition and oxygen from the mother, and some brain functions related to long-term memory. Through our long evolution, our immune system became stronger, more efficient and sophisticated.

In the 21st century, we have more than 40 different types of immune cells that are working together in our bodies, forming an elaborate defence network to maintain health and vital functions. While we are eternally evolving along with our cells, viruses too have been evolving, gaining more powerful and elaborate techniques to break through the defences of our bodies. The current war being waged between our immune network and COVID-19 is at its most intense in the shared evolutionary history of mankind. Luckily for us, new insights into the working of our immune system and viruses are providing effective measures to counter the novel coronavirus.

Before the vaccines were released, a patient was infected with COVID-19 and slipped in a coma for 8 days. The first signs were similar to the regular flu, however within 5 days the man had trouble breathing and had to be admitted to hospital and was later transferred to the ICU where he would be put on a ventilator. In these early days against COVID-19, three different drugs were administered to him as part of a clinical trial in a desperate attempt to prevent him from dying, however his condition did not improve – medical professionals were running out of options and time. Then, he was given a special treatment and miraculously regained consciousness within 4 days and a very quick recovery followed. That patient was saved with the blood of another individual who could be said to possess special powers as a COVID-19 survivor. The antibodies contained in the blood of the COVID-19 survivor were collected and injected in the critically ill patient’s body. This treatment is known as convalescent plasma therapy.

Remember! Earlier we explained that: (1) when the virus enters and infects cells, blue interferons are released to alert the phagocytes to take action and devour the viral cells, but since the COVID-19 virus has a mutated gene that supresses the blue interferons, phagocytes cannot be mobilized; (2) the immune system then uses the phagocytes as messenger to carry viral particles as information to the blue immune cell that becomes activated as a killer T cells which then locates protrusions on infected cells’ surfaces to inject toxin and destroy both virus and cell, however, since the virus uses another cunning technique to break down the clasps protruding through infected cells, the T cells fail to detect those infected cells; (3) those 2 solutions were part of our innate immune system, and when they fail the body relies on the adaptive immune system to pass information through phagocytes to the B cells that release the life-saving yellow particles known as antibodies, and when a COVID-19 patient reaches this stage they are out of danger.

That convalescent plasma therapy which saved the above patient’s life is about collecting those amazing Y-shaped yellow particles known as antibodies which are produced by patients who successfully fought the COVID-19 virus. As already explained those yellow antibodies are projectile weapons tailor-made by immune cells based on the information they received on the virus from the messenger phagocytes. We know that antibodies released by B cells engulf the viral cells disabling them and preventing them to replicate, hence these antibodies are powerful weapon that target the COVID-19 virus. Fortunately for the critically ill patient above, the donor’s body was able to produce vast amounts of antibodies from his B cells. When those antibodies were injected in the body of the patient, they successfully disabled and eliminated the virus.

Hence, convalescent plasma therapy treatment is a proven solution expected to save lives as the COVID-19 continues its devastating rampage across the planet. Vaccines may be available, but it will take some time to vaccinate the whole planet, and even if the world is vaccinated, some people may still develop severe symptoms. So, having a stock of convalescent plasma at hand will always be the safest bet in preventing deaths from COVID-19. It seems noble and reasonable for health authorities worldwide to ask COVID-19 survivors to donate their blood, as their antibodies will save lives.

Image: Convalescent Plasma Therapy [Life-saving antibodies created by the B cells of a COVID-19 survivor are collected from his blood, ready to be injected in the body of a patient with severe symptoms]

Research has shown that some individuals have the incredible ability to produce vast amounts of antibodies, enough to save the lives of patients with life-threatening symptoms. Blood was collected from 149 COVID-19 survivors. The graph shows the levels of antibodies found in their blood samples and we can see that they vary from patient to patient; some are able to produce 10 times more antibodies than the average. (Robbiani et al., 2020)

Graph: Level of antibodies produced by the patients who recovered from COVID-19 in the study. (Robbiani et al., 2020)

So what is the difference between people who are able to produce large amounts of antibodies when infected by the novel coronavirus and those who don’t?

The answer to this question is remains a mystery but scientists have a theory. The answer may lie in the moment when antibody production is triggered, i.e. when immune cells holding viral fragments pass on the message [enemy intel] to the B cells of our adaptive immune system which then produce antibodies based on this information. The key here is the shape of the clasp that comes from the messenger immune cell. We know that there are more than 10 000 types of those clasps and they vary from one individual to another.

Image: There are more than 10 000 differently shaped clasps and those vary from one individual to the next

Some clasps have a better grasp [i.e. they can hold on more firmly] to the fragment of the novel coronavirus, hence they keep sending out precise intel to allow large amounts of antibodies to be made. But some people who have differently shaped clasps [i.e. clasps that do not perfectly fit the shape of the viral fragment] lead to their messenger immune cell not being able to grip the viral fragment perfectly, this leads to a lack of precise information being passed on to the B cells, and hence lower amounts of antibodies are released.

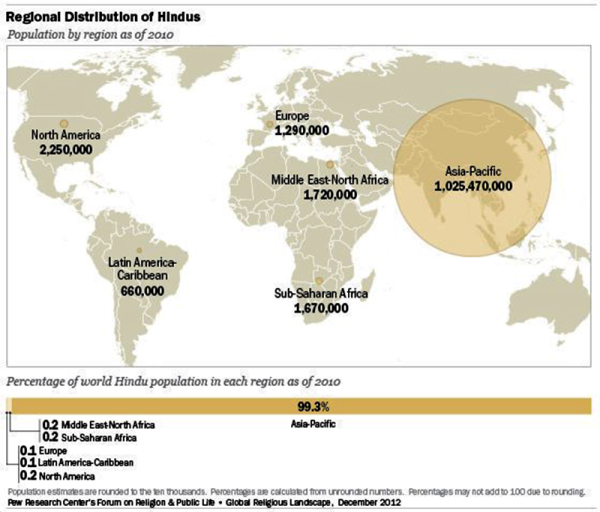

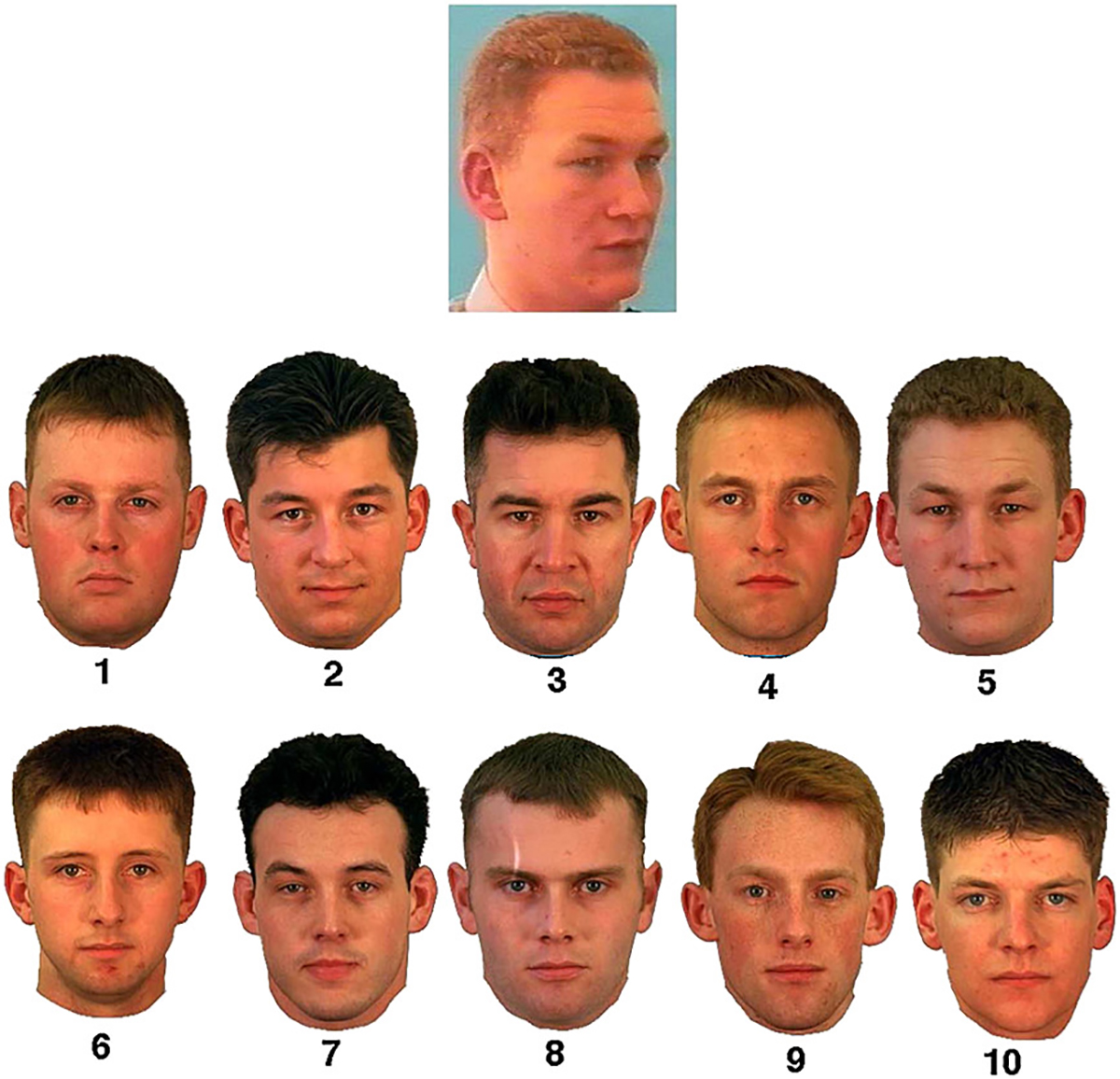

Interestingly, we are beginning to understand that these differences may be associated with geography and ethnicity [Note: Ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups such as a common set of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area(s). Ethnicity is sometimes used interchangeably with the term nation].

People across the planet have inherited differently shaped clasps better suited to fight against the viruses in their area throughout evolution. This evolution is eternal as the human race evolves.

In Africa, for example, we can find many people with clasps that are better suited for holding to fragments of the malaria parasite, meanwhile in south-east Asia there are many people who have the most suitable types of clasps to grip fragments of the bacteria responsible for leprosy. Scientists believe that these differences from different groups from different locations across the planet come from variations in a particular gene known as HLA, which is responsible for shaping the clasps of the immune cells in our bodies.

Katsushi Tokunaga of the Genome Medical Science Project from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine explains: “Many types of pathogens have emerged throughout our history. In different regions at different ages. That is why mankind has acquired different HLA types to fight off different pathogens.”

About 200,000 years ago, our ancestors, the early primates, left Africa and began to explore and migrate to different parts of the planet. Wherever they moved to, just like us today, they also had to face viruses and pathogens. After each attack, it is believed that their immune system and HLA gene adapted; so these clasps suitable to face new enemies have been passed on to us through the long journey of evolution.

Image: Each individudual has inherited a uniquely shaped clasp from their individual evolutionary history

Katsushi Tokunaga: “The diversity of HLA’s is our defense against the range pathogens. So only those who excelled in the fight against them left their HLA types as a legacy to us.”

We still cannot know when or how some individuals have acquired the incredible ability to develop those amazing clasps that are so well adapted to fight off the COVID-19 virus; the most rational explanation seems to be that individuals in their evolutionary lineage in the past experienced infections from viruses that shared a great deal of structural similarity with the novel coronavirus, hence they have acquired clasps that just happen to perfectly fit the shape of the COVID-19 virus. Every individual on our planet has inherited different shapes of clasps within their immune cells to fight off viruses. This is our heritage from our shared evolutionary history as primates on earth and a testament to our primitive ancestors who had fought and survived an incredible variety of infections diseases throughout evolution.

Today, cutting-edge medicine is attempting to harness the immune super powers of the few incredible individuals so that lives all over the world can be saved by passing down their immunity [i.e. the antibodies created by their B cells ]to fellow humans.

At the Lilly Technology Center, scientists are culturing immune cells collected from those individuals with super powers who can produce large amounts of COVID-19 antibodies. They are hoping to produce antibodies in vast quantities so they can be used to save the lives of patients suffering from the severe life-threatening symptoms of COVID-19 worldwide. Clinical studies are already underway and the academic community is hopeful that convalescent therapy treatment will be widely available.

Pamela J. Bjorkman from the California Institute of Technology Eppendorf said: “I think we could make things in the laboratory that would work better than what people are making. And maybe those would work at very low concentrations and make a practical way of delivering to people to protect them or help them if they’re actually sick. This is definitely a possibility. And I think it’s a very hopeful one too. If anyone was sick and they were willing to donate their plasma to help other people and to help science, then yes, they are definitely heroes.”

The planetary war agains COVID-19 continues with no end in sight. However, it is important to note that our immune networks have been supporting us since birth and will do so until we take our last breath.

From birth, the moment we leave the vagina and take our first gasp of air on this planet as infants we are exposed to many different pathogens like viruses and bacteria. But the immune cells of babies are not yet ready to fight back. The first protection for the baby comes from the mother’s breast milk, which contains large amounts of immune cells and antibodies belonging to the mother; those help the baby’s own immune cells to develop while also providing protection from various bacteria and viruses.

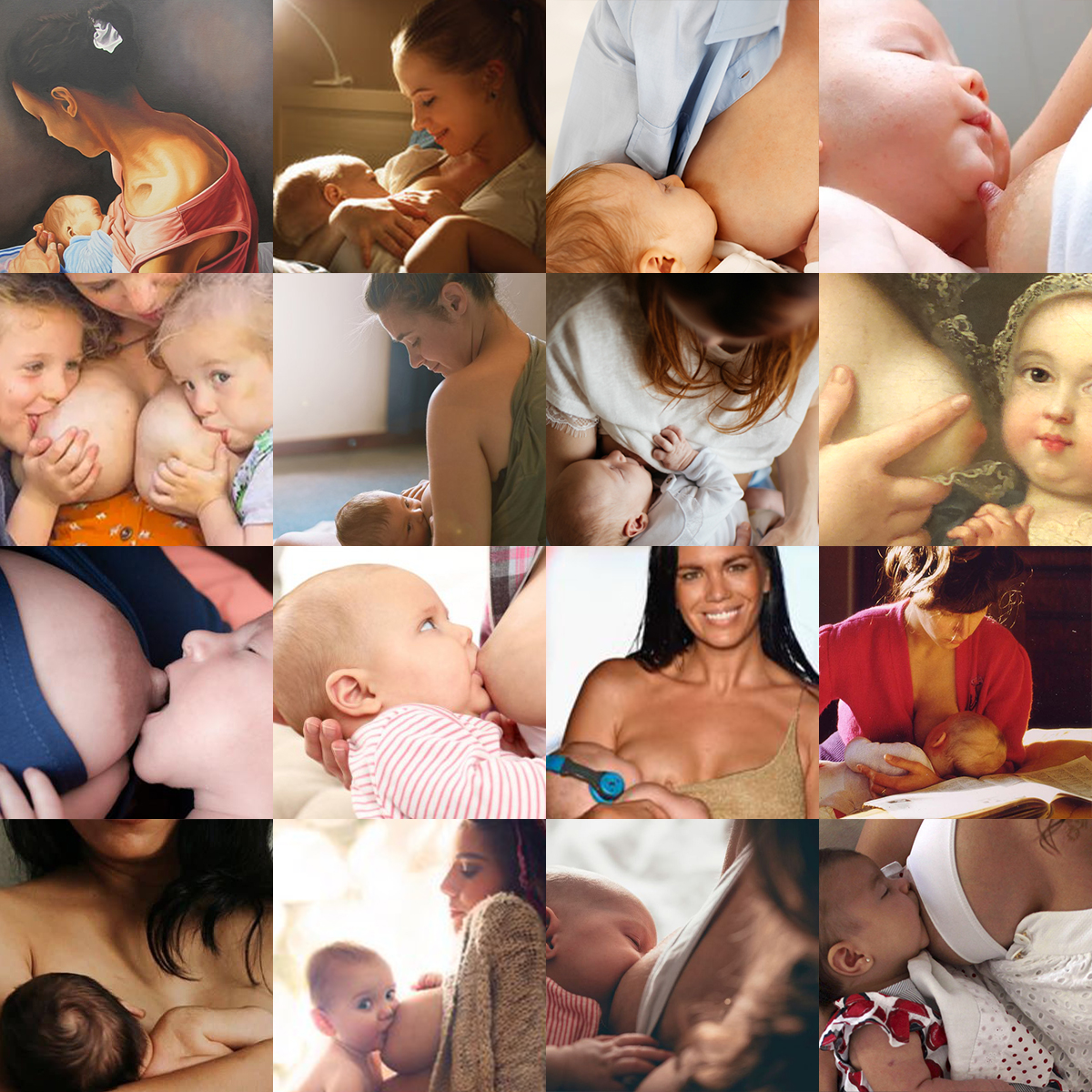

Image: Des mères allaitant leur bébés / Mothers breasfeeding their babies

After several months, the baby’s own immune networks begin to kick in, and in the years that follow through exposure to various types of viruses and bacteria our immune system continues to develop and grow stronger. It had previously been thought that the immunity of human beings reaches its peak around 20 years of age and then flattens out, gradually declining at around the age of 70.

But during the current COVID-19 pandemic incredible recoveries have been observed across the planet from individuals in the 70s, 80s and even some centenarians. Studies suggest that these incredible individuals have something “special” in their bodies that is keeping their immune cells young.

3 COVID-19 survivors who are above 90 years of age: (i) Connie Titchen (106, from the UK); (ii) Albert Chambers (100, from the UK); and Maria Branyas (113, from Spain)

The mystery of the human body remains and we know that it is a remarkable system supported by specialist cells that protect our lives with their unique skills honed over 4 billion years of evolution. The keys to overcoming this pandemic and future ones might just be locked away in our own bodies and it could be hidden in some incredible individuals out there.

It is important to note that these findings are just the beginning, and it will take years of serious research to fully understand COVID-19 along with the range of cardiovascular and immune effects it might trigger as new variants continue to evolve. We can only hope to find a way to stop this ugly virus in its track through the combined efforts of planet Earth’s scientific force and medical geniuses.

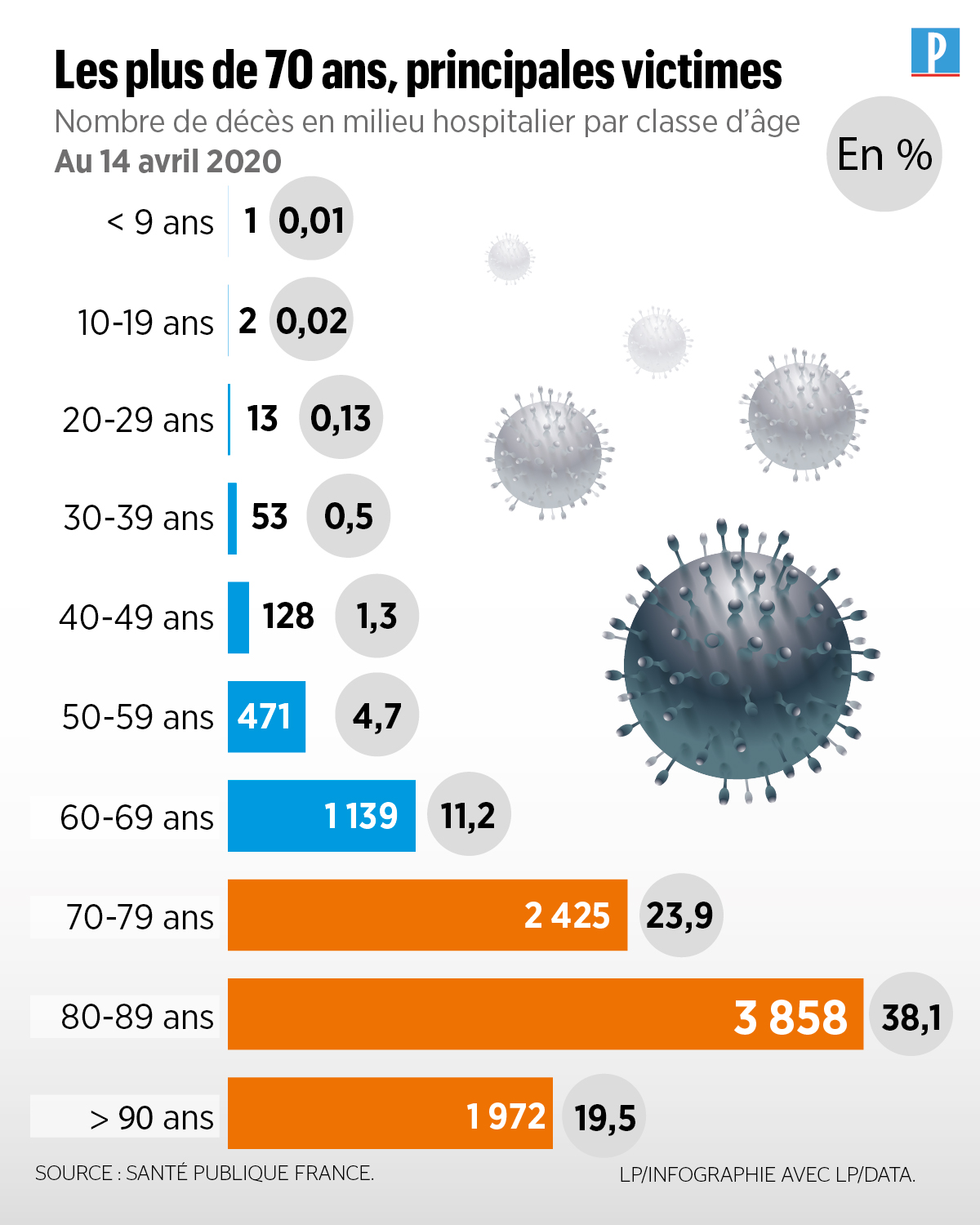

At present, whilst COVID-19 appears to be more contagious than SARS or MERS, the fatality rate is relatively low (around 3%) when compared with MERS (34%) and SARS (10%), with early data suggesting the elderly and those with underlying health conditions are at a higher risk.

In France, if Mentonians are concerned about coronavirus, it is in fact mainly for their elders. « Menton is a town of old people. If the epidemic spreads, they’ll all be dropping like flies. It’s going to be no man’s land, » said Denis, arm in arm with his 88-year-old mother. « I’m not afraid for myself: I know the virus won’t kill me. But I’ve told my mother, ‘you’re not going out of the house any more,’ » explained Véronique, in her fifties, as she folded a tablecloth from her shop in the centre of town.

By advocating the use of chloroquine to treat people suffering from Covid-19, the brave maverick, Professor Didier Raoult became the target of criticism in a very short time. Raoult did, however, receive some support, notably from Jean-Marie Bigard, who recounted one of his telephone conversations with the much-scorned professor. « We talked about how he thanked me for supporting him (…) And then he said something funny to me, saying: ‘All the time I was thinking about this story, I only thought about one thing, and that was your sketch about the bat,’ » the comedian said. Furthermore, even if it is not a miracle cure, a range of other medical professionals claim to have successfully treated a range of COVID-19 sufferers with hydroxychloroquine, while some studies have shown its ability to inhibit the virus in vitro.

Image: Didier Raoult au micro d’Apolline de Malherbe

Didier Sicard a professor from Sorbonne University also a specialist in infectious diseases who has a long experience in scientific work on the HIV, argued that researchers should go back on the field and inquire on the animal origin of the epidemic. Professor Sicard noted that the abrupt transformation of primary forests has brought humans closer to bats and hence a reservoir of viruses that has not yet been closely studied.

While China has only recently, on the 24th of February 2020, immediately and completely banned all traffic and consumption of wild animals, conscious of its dietary culture of eating practically anything that moves, it is important to note that such a legislation exists since 2003 without it being strictly respected by Beijing. Hence, Professor Sicard reasonably argues for an international health court. The former Chair of the Advisory Committee on Ethics from 1999 to 2008 emphasizes the extent to which, in this epidemic, the issue of contact is paramount – everyone must behave like a model.

Image: Femme consultant son médecin / Woman consulting her doctor Source: AFP – B. BOISSONNET

Sicard also points out that the starting point of this pandemic is an open market in Wuhan where wild animals, snakes, bats, pangolins, preserved in wicker crates, accumulate. In China, these animals are bought for the Rat Festival and are quite expensive and considered as food of choice. In this wild meat market, these animals are obviously touched and handled by the vendors throughout the day, skinned, while they are stained with urine; ticks and mosquitoes also make a kind of cloud around these poor animals by the thousands.

These conditions have meant that a few infected animals have inevitably infected other animals within a few days. One can hypothesize that a vendor injured himself or touched contaminated urine before putting his hand to his face. Here we go! What strikes Sicard is the indifference at the starting point of this ugly virus. As if society was only interested in the point of arrival: the vaccine, the treatments, the resuscitation. But for this not to happen again, the starting point should be considered vital. And it’s impressive to see how it’s being neglected. The indifference to wildlife markets around the world is dramatic. It is said that these markets bring in as much money as the drug market. In Mexico, there is such a traffic that customs officers even find pangolins in suitcases.

Image: Un pangolin sauvé au Mexique par la Wildlife Alliance / A pangolin being rescued in Mexico by the Wildlife Alliance

Chart: Estimated number of Asian pangolins in international trade between 1977 and 2012 as reported to CITES, and estimated number of pangolins in illegal trade in Asia between July 2000 and 2013. Illegal trade is based on seizures made in or trade recorded in Cambodia, China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan (P.R. China), Thailand and Vietnam. Source: CITES trade database (UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK), and for illegal trade, various sources / Source: (Challender, Harrop and MacMillan, 2015)

Jean-Christophe Ruffin, a doctor, diplomat and writer from the Académie Française said: “Now is not the time to burden anyone and sue, it will come. But they’ll have to be done. We’ll have to learn from this. This proves one thing: when we get out of this terrible crisis, as infectious disease specialists say, there will be others. And we can’t be in a situation like that again.”

« It is of course not the first time that animals are at the origin of sanitary crises, in fact they are responsible for the majority of epidemic crises: HIV, H5N1 avian flu, Ebola. These viral diseases always come from a reservoir of animal viruses », Sicard pointed out, and there’s almost no interest in them. It’s the same with dengue fever. “I have a very close relationship with Laos, and when the disease appears, the local people there say, ‘We have to control the mosquitoes’. But in reality, it is during the dry season, when there are only larvae, that a policy of exterminating mosquito larvae should be implemented. But nobody does it because people say ‘oh, there are no mosquitoes, why do you want us to use insecticides? And the Pasteur Institute of Laos is sputtering in vain, asking local people to make the effort before the disease bursts”, Sicard explained to France Culture, saying “It is exactly like the work that’s left to be done on the bats. They are themselves carriers of about 30 coronaviruses! We need to do some work on these animals. »

Image: Pangolin sauvé des mains d’un trafiquant local, Uganda. 9 avril 2020 • Crédits : Isaak Kasamani – AFP

The latter also added: « Obviously, it is not very easy: going into caves, well protected, taking vipers, pangolins, ants, looking at the viruses they harbour, this is ungrateful work and often despised by laboratories. Researchers say: ‘We prefer to work in the molecular biology laboratory with our cosmonaut hoods. Going into the jungle, bringing in mosquitoes, is dangerous. Yet, these are by far the most important routes.

Moreover, we know that these epidemics will start again in the years to come repeatedly if we don’t definitively ban the traffic of wild animals. This should be criminalized as an open-air sale of cocaine. This crime should be punishable by imprisonment. I am also thinking of those battery farms for chicken or pork that are found in China. Every year they give new flu outbreaks from viruses of avian origin. Gathering animals like that is not serious. It is as if veterinary art and human medical art had nothing to do with each other. The origin of the epidemic should be the subject of a major international mobilisation.”

Prof Sicard argued that we need to reconstruct the epidemiological pathway by which bats have tolerated coronaviruses for millions of years, but have also dispersed them. It contaminates other animals.

Letko, M., Miazgowicz, K., McMinn, R., Seifert, S., Sola, I., Enjuanes, L., Carmody, A., van Doremalen, N. and Munster, V., 2018. Adaptive Evolution of MERS-CoV to Species Variation in DPP4. Cell Reports, 24(7), pp.1730-1737.

When bats hang in caves and die, they fall to the ground. Then the snakes, vipers in particular, who love their corpses, eat them. Just like the young bats that fall down and are immediately eaten by these snakes which are therefore probably intermediate hosts for viruses. In addition, there are clouds of mosquitoes and ticks in these caves and we should try to see which insects are also possible transmitters of the virus. Another hypothesis concerns the transmission that occurs when bats go out at night to eat fruit. Bats have an almost automatic reflex; as soon as they swallow, they urinate, explained Sicard. They will therefore contaminate the fruits of these trees and the civets, which love the same fruits, hence contaminating themselves by eating them. The ants participate in the agape and the pangolins – for which the most wonderful food is ants – devour the ants and become infected in their turn. It is this whole chain of contamination that needs to be explored. Probably the most dangerous reservoirs of viruses are snakes, because they are the ones that are constantly feeding on bats, which are themselves carriers of coronaviruses. Snakes could therefore be a permanent host for these viruses, and obviously eating them is not only disgusting but dangerous. But that is exactly what we need to know and check. Researchers should therefore capture bats, but also do the same work on ants, civets, pangolins and try to understand their tolerance to the virus. It’s a bit ungrateful, but essential.

Didier Sicard also elaborated on the relation between the local Eastern Asian population and the bats, saying “What struck me in Laos, where I often go, is that the primary forest is regressing because the Chinese are building stations and trains there. These trains, which cross the jungle without any health precautions, can become the vector of parasitic or viral diseases and carry them through China, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia and even Singapore. The Silk Road, which the Chinese are in the process of completing, may also become the route for the spread of serious diseases. Caves are becoming more and more accessible there. As a result, humans tend to get closer to where the bats live, and bats are also a highly sought-after food source. Humans are now also building fruit tree parks close to these caves because there are no more trees due to deforestation. The inhabitants feel that they can gain territory, like in the Amazon. And so, they are building agricultural areas very close to extremely dangerous virus reservoir areas. I don’t have the answer to all these questions, but I just know that the starting point is not well known. And that it’s totally ignored. It’s being turned into folksy conference speeches. They talk about bats and the curse of the pharaohs.”