Mis à jour le Jeudi, 13 Février 2020

Part 1 of 5 | Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health Services (CAMHS) & Learning and Intellectual Disabilities

CAMHS deal with the psychological issues of people under the age of 18. They are a non-specialist service and often refer to other more specialised departments following the initial assessment of patients. The most common cases tend to be adolescents with depression and anxiety whose manifestations are not different to those of adults and so are treated fairly similarly.

Inclusivism in Learning Disabilities

In 1969, Bengt Nirje adopted and developed the concept of normalisation in Sweden and beautifully described it as…

“making available to all mentally retarded people patterns of life and conditions of everyday living which are as close as possible to the regular circumstances and ways of life of society.”

– Nirje, 1980

Learning Disability is not just an impairment in Cognition

The social impairment of Learning Disabilities – US Statute 111 – 256: Rosa’s Law defines the factual impairment, the imposed or acquired disability and the awareness of being different.

The Normalisation Theory

This theory focuses on the mainstream trends of social devaluation or deviancy making. Some categories of people tend to be valued negatively due to their behaviours, appearances and characteristics, and this places them at the risk of being devalued [according to the Normalisation Theory of Nirje on the societal processes he assumed] – people fulfil various social roles and stereotypes.

As part of the deviancy making or social devaluation, the unsophisticated minds of the masses generally do not mean to stereotype, however they seem to do it unconsciously [the unconscious is a concept Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan acknowledged in their psychoanalytic theories of mental/psychological activity and mental health problems linked to psychopathic tendencies in people towards others], i.e. deviant groups with social symbols or images that are at a higher risk of being devalued are the focus of the normalisation theory, which is believed to be done with the aim of providing them with the skills they need and eventually change the status of these deviant groups to functional members of society.

Lutte contre l’illettrisme En 6ème, je ne savais pas écrire mon nom ! (2016)

Society tends to distance itself from deviant groups without any purpose or belonging, however psychologists provide support for the social integration and valued social participation of people with learning disabilities through exercises that involve learning through imitation. This challenges stereotypes within wider society through direct experiences of spending time with people who are affected by learning disabilities.

While psychology evolves and sophisticated and modern theories about intelligence and communication such as our “Organic Theory” take shape, we hope that observations such as this one may be digested and understood by the masses, that is:

“While the communicative patterns [language] in human primates vary with socio-behavioural and geographical patterns; creativity and IQ remain constant and do not change. Intelligence and creativity cannot be stopped because of linguistic differences, since talented and gifted humans do not choose the location of their birth nor their linguistic heritage but still contribute to the enhancement of our civilisation.”

Which concludes that that the intelligence of an invidual when assessed on a range of variables [e.g. perception, fluid intelligence, artistic creativity, reasoning, emotional intelligence, courage, values, etc] cannot be deduced by simply assessing their academic abilities, since human life has various sides to itself. Hence, the true worth and value of an individual may always remain a problem and a mystery to fully assess [since most only assess people on the variables they are interested in, for e.g. a company looking for a secretary will assess the applicant on her ability to handle office politics, and not other abilities essential to exist as a human within civilisation], and this seems to go in line with Jean Piaget’s deduction about the uniqueness of the human organism and mind.

“I am still learning” – Michael-Angelo at the age of 87 / Image: La Création d’Adam (1508 – 1512)

Neurodevelopmental Disorders & Intellectual Disabilities

Neurodevelopmental disorders are disorders occurring due to the biological dysfunction of the brain that in turn lead to developmental deficits that come in a range that can be very specific to global impairment. These groups however often co-occur together, i.e. one could be affected with Intellectual Disability (ID) and also Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Psychologists are expected to show great care when assessing this group of disorder as they vary in severity. Severity has 4 Specifiers and 3 Domains [Intellectual].

Specifiers: [1] Mild – [2] Moderate – [3] Severe – [4] Profound

Domains [Intellectual]: [1] Conceptual – [2] Social – [3] Practical

Intellectual Domains

The first domain, which is the Conceptual Domain refers to all things learnt at school and required for employment and adequate independent functioning within the community. Secondly, the Social Domain refers to social, developmental and emotional factors associated to age. This manifests in them as being victims of manipulation and abuse by others. Finally, the Practical Domain refers to all skills required to live healthily [also this is subject to interpretation depending on contexts, socio-linguistic and cultural settings].

Intellectual Disability

For one to be qualified as intellectually disabled, we would have to meet all the 3 criteria below:

- Deficits in intellectual functions, such as reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgement, learning [also from experience].

- Deficits in adaptive functioning that means failure to meet developmental milestones within the socio-cultural standards. Limited function in daily life, participation, communication, independence in multiple environments (i.e. Global).

- Onset is during developmental period [childhood – another link to the Psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud & Jacques Lacan]

Assessment and Judgement

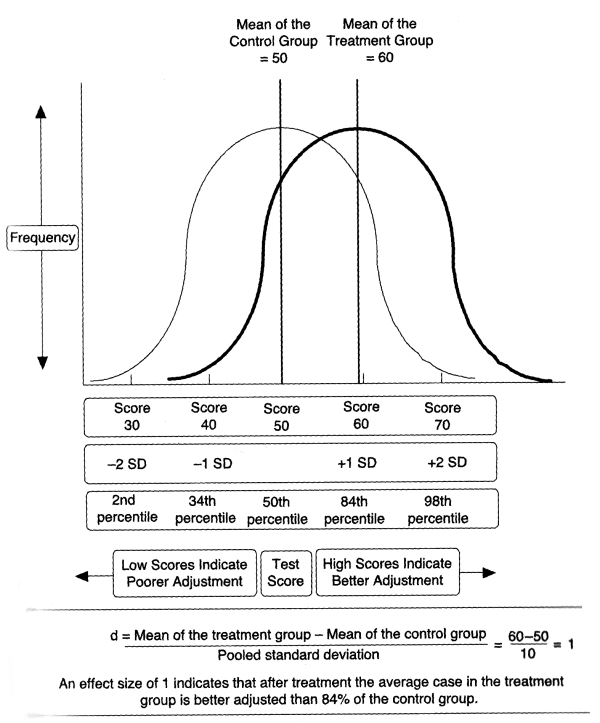

Careful distinction must be made when assessing patients suspected of suffering from Intellectual Disabilities (ID) between the low end of normal function and ID itself. The most widely used method clinically are IQ assessments and typically suggest any score that is 2 Standard Deviations below the mean [IQ scores of 75 +/-5] and whether the patient has had any clinical experience. Assessment based on the patient’s reasoning in real-life situations are also made. Global Developmental Delay is a term reserved for children under 5 who cannot adequately be assessed, but have missed all their developmental milestones.

Associated Features with Intellectual Disabilities (ID) to look for when diagnosing patients are:

- Social judgment

- Assessment of risk

- Self-management of behaviour – interpersonal relationships and emotions

- Motivation in school, university or work

- Lack of communication skills and functional problem behaviours

- Gullibility [Diagnosis is based on how people and society mistreat them – quite shocking or controversial?]

- People with Intellectual Disabilities (ID) are also at high risk of suicide

Prevalence of Intellectual Disabilities

In the UK, 1% of people suffer from intellectual disabilities and 0.006% of the population have severe disabilities requiring supported living [that is about 360, 000 people in the UK] – a slight bias with a ratio of 1.6:1 towards males; this is due to the vulnerability of the male brain.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

As psychology evolves more consideration are being given to a dimensional aspect of abnormal behaviour rather than the usual dimensional [i.e. inflexible and sometimes exaggerated in terms of descriptive precisions disregarding individual fluctuations in symptomatic manifestations] constructs of mental disorders. Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) was the first mental disorder to initiate such a shift from categories to dimensions.

- Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) with Intellectual Disability (ID) = Autism

- Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) without Intellectual Disability (ID) = Asperger’s Syndrome

Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders

ASD is characterised mainly by deficits in social communication and restricted patterns of behaviour. For a diagnosis of ASD the deficits must appear early in the developmental period [however they cannot be diagnosed until the demands of a particular task exceeds the child’s capabilities] – so more severe it is the earlier it is diagnosed [e.g. Rett syndrome].

[A] Communication in ASD

In ASD, it is common to find persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts illustrated by:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging from abnormal social approach. Failure to initiate or respond to social communications. Reduction in sharing interests, affect and emotions.

- Deficits in non-verbal communicative behaviours used in normal social interactions. Abnormal or no eye contact, body language or deficits in reading [understanding] gestures. A total lack of facial expression and non-verbal communication.

- Deficits in developing, maintaining and understanding relationships [e.g. from difficulties in adjusting behaviour to suit context]. Difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making positive social acquaintances or friends. Hardly any interest in any form or peers.

[B] Behaviour in ASD

It is also fairly normal to notice restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities manifested by at least two of the following:

- Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech

- Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualised patterns of behaviour. Shows extreme distress at small changes, difficulty in transition, rigidity, insistence on same route taken or foods

- Hyper or hypo-reactive to sensory inputs or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (indifference or hyper-responsive to pain, temperature, sound, textures, excessive smelling to touching of objects, visual fascination with movements or lights.

ASD may also manifest itself with or without intellectual disability, with a similar scenario for language impairment, and can be associated with medical or genetic conditions or environmental factors [exposure]. ASD can also be associated with another neurodevelopmental, mental or behavioural disorder and can also comprise catatonia.

Features to look out for

- People with ASD often have uneven profiles or abilities – even the high functioning variants, and this can lead to substantive stress for them

- They also often have odd motor idiosyncrasies – such as an odd gait, clumsiness and abnormal ambulatory movements.

- Disruptive, challenging behaviour and injuries are also very common

- As sufferers of ASD age, they are also more prone to developing anxiety and depression and are likely to end up in a catatonic state

Prevalence

Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) seem to be a genetic disorder, however it involves a variety of genes. 15% of ASD is due to a known mutation in over 90% of concordance studies with twins. Most researchers nowadays suggest that it is inherited and polygenic [lots of genes from genetic ancestry with each adding their weight to the likelihood of the disorder manifesting]. Males are 4 times more likely to suffer from ASD than females, and even high functioning adults with ASD have poor functioning, such as low rates of independent living and employment – older adults tend to become isolated and do not engage in help-seeking behaviours [note that this is different to individuals who may have a solitary personality by conscious choice or a highly selective social circle in personal relationships based on values, in ASD the patients are generally not conscious of the causes of their debilitating condition]

Specific Learning Disorders

Specific Learning Disorders are characterised by the following:

[A] Difficulties learning and using academic skills, as indicated by the presence of at least one of the following symptoms that has persisted for longer than 6 months:

(1) Inaccurate or slow reading

(2) Difficulty understanding meaning in what was read

(3) Difficulties with spelling

(4) Difficulties with written expression

(5) Difficulties mastering number sense, number facts and calculation

(6) Difficulties in mathematical reasoning

[B] The affected academic skills are substantially and quantifiably below the expected level for the chronological age causing interference with academic, occupational or daily living

[C] Learning difficulties begin during school-age years, but will only manifest itself and be diagnosed when the affected person’s capabilities are stretched by demands

[D] It is also independent and not caused by another health or psychological disorder

Specifications of Specific Learning Disorder

SLD generally involves impairment in reading, writing and mathematics. If it is mild in intensity, the person can generally compensate. Moderately affected people however cannot compensate, but will respond to specialist teaching. Finally, severe conditions require specialist teaching in a specialist school as learning will not occur without such arrangements.

Features to look out for in confirming SLD

- SLD can occur in any individual, even those classed as gifted (IQ 130+)

- It is usually diagnosed in the early years, but in higher ability individuals it may manifest in odd ways especially when their compensatory methods are undermined

- Patient generally have difficulties with motor co-ordination

- It is a life-long condition and does not improve with therapy, but has to be compensated for

- Patients also tend to have working memory deficits and keep messy environments

- Early signs include mispronouncing words, struggling to break down words into syllables

Prevalence of Specific Learning Disorders (SLD)

SLD tend to occur in premature children or among societies with a very low birth rate. It is also more common in children with parents that smoke cigarettes [nicotine?] and is 8 to 10 times higher in families with a heritability index of 0.6 and 3 times higher in males [the vulnerability of the male brain once again]. The problems it causes with attention are likely to predict problems with the mathematical and reading components of the brain. SLD usually ends with unemployment, under-employment depression, poorer mental health and suicidal behaviour – support of any kind alters all of these outcomes.

_____________________________________

Part 2 of 5 | Anxiety Disorders

Source: World Health Organisation

Anxiety disorders are linked to the development of irrational fears of situations that are not life-threatening (Antony & Stein, 2009a). The avoidance of feared situations or experiences also lead to non-adaptive behavioural patterns. People suffering from anxiety disorders generally have fears accompanied by intense physiological arousal displayed by some or all of the following features: accelerated heartbeat, sweating, trembling, sensations of shortness of breath or smothering feelings of choking, chest pain, nausea, numbness or tingling, and chills or hot flushes. Other experiences of dizziness, derealisation (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (feelings of being detached from the self) are also present in some cases.

In contemporary psychology there are a number of distinctions made between a variety of anxiety disorders based on the developmental timing of their emergence, the classes of stimuli that elicit the anxiety, the pervasiveness and topography of the anxiety response, and the role of clearly identifiable factors in the aetiology [the cause, set of causes, or manner of causation] of the anxiety.

The six main anxiety disorders are described below.

[1] Separation Anxiety

This condition most occurs in children and is generally manifested by a recurrent and persistent fear that is aroused when separation from the parents or caregivers is anticipated or imminent (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Furr et al., 2009; Pine & Klein, 2008; World Health Organization, 1992). The persistent, excessive worry about losing, or about possible harm befalling a parent is the main characteristic of Separation Anxiety Disorder with nightmares on the similar themes also present in some cases along with recurrent head-aches, stomach-aches, nausea and vomiting. Separation anxiety is also one of the most common causes of school refusal, and sufferers may also display a refusal to sleep without being in close proximity with the parents.

[2] Phobias

Phobic anxiety is the irrational and intense fear aroused when one is faced with an object, event or situation from a clearly defined class of stimuli which is exaggerated in terms of danger posed (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Blackmore et al., 2009; Hofmann et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 1992). When the person affected is exposed to the phobic stimulus, or anticipates its exposure, panic attacks may arise in adults whereas is children this may lead to excessive crying, tantrums, freezing or clinging. The persistent avoidance of phobic stimuli in phobias is endured with intense distress and this affects an individual’s personal functioning.

In the DSM, specific phobias are subdivided into those associated with animals, injury (including injections), features of the natural environment (such as heights or thunder), in particular situations (such as elevators or flying). These specific phobias are different from social phobias and agoraphobia.

In those affected with social phobias, anxiety is generally mainly aroused by social situations [e.g. public speaking, eating in public where there is the possibility of scrutiny by others and humiliation or embarrassment as a result of acting inappropriately]. In those with agoraphobia, the condition is known to manifest itself with panic attacks in public places, such as being in a queue, or on public transport – hence, these situations tend to be compulsively avoided to prevent the reoccurrence of the panic attacks.

[3] Generalized Anxiety Disorder

One of the main characteristics in general anxiety disorder is the constant feeling that misfortunes of various sorts will occur (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Bitran et al., 2009; Hazlett-Stevens et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 1992) and the anxiety is not focused on one particular object or situation along with difficulties controlling the worrying process and a belief that worrying is uncontrollable.

General anxiety disorder is mainly composed of nervousness, restlessness, difficulty relaxing, feeling on edge, being easily fatigued, difficulties in concentration, irritability, tearfulness, sleep disturbance and signs of autonomic over-reactivity such as trembling, sweating, dehydrated mouth, light-headedness, palpitations, dizziness and stomach discomfort. [DSM requires some or more of those symptoms to be present]

Case Example of Generalised Anxiety Disorder

Margie, a 10 year old girl was referred to the psychologist after displaying excessive tearfulness in school, the condition which had been gradually amplifying over a number of months and the bouts were unpredictable. Margie would often end up in tears while playing with her friends during break time or when spoken to by the teacher. In the family doctor’s referral letter she was described as a worrier like her mother.

Presentation

in the assessment interview Margie explained that her worries were mainly about a routine daily activities and responsibilities, she would also worry about doing poorly at school and that she had made mistakes which would later be discovered, that her school friend would not like her, that she would disappoint her parents with the way she did her household chores, that she would either be too late or too early for the school bus, that there would not be any space for on the bus and that she would forget her school books. Her worries also extended to health with frequent stomach aches.

The safety of a family also troubled her, she would worry that her house would be struck by lightning, that the river would break its banks and flood the low-lying fens where she lived, washing away her whole house. The future was also a major concern of hers as she worried about failing her exams and being unable to find a satisfactory job, and being unable to find a marital partner or marrying an inadequate person. A continuous feeling of restlessness with the inability to relax was also reported by her.

Family History

The family was very close and Margie was the eldest of four children and the only girl. It was observed during the intake interview that the mother and the father displayed symptoms of anxiety, while the former had been treated with benzodiazepines for anxiety over a number of years. The family also admitted to regularly discuss their problems about their own health and safety and their own worries about the uncertainty of the future.

The father, Oliver was employed by the insurance company and regularly have conversations at the dinner table about the accidents and the burglaries that had befallen his client, and Margie regularly participated in these conversation, being the eldest among her siblings. However the main concern of the parents was about Margie’s tearfulness which they believed was unusual along with her worries and fears which they thought as legitimate. Margie spent a lot of time with her parents’ company but also had a couple of close friends with whom she played at the weekends.

Formulation

Margie was diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder. The precipitating factor for the condition was not apparent as it had gradually evolved over the course of Margie’s development. The referral however, was precipitated by episodes of tearfulness at school. The predisposing factors in her case comprised of a highly likely possibility of genetic vulnerability to anxiety and exposure to family culture characterised by an excessive concern with safety and oversensitivity to dangerous situations. The ongoing parental conversations about potential threats to the family’s well-being likely maintained the condition along with inadvertent reinforcement of Margie’s tearfulness at school, where her tears were responded to with considerable concern.

The protective factors in the case included good premorbid adjustment, the parents’ and the school’s commitment to solving the problem and the availability of peer group support. [This formulation is diagrammed below]

Treatment

In this particular case, treatment involved family work focused on helping Margie parents reduce the amount of time they spent discussing themes related to danger and threats to their health and safety, and increase the amount engaged in activities and discussions focused on Margie’s strengths and capabilities. The parents were also assisted in coaching Margie into learning relaxation skills and mastery oriented coping self- statements. Eventually Margie showed improvement in her adjustment in school with some reduction in anxiety and tearfulness.

[4] Panic Disorder

In panic disorders, there are recurrent unexpected panic attacks; an ongoing primary fear of further attacks; secondary fear of losing control, going insane, having a heart attack or dying (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Ballenger, 2009; Hofmann et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 1992). Acute episodes of intense anxiety our experienced in panic attacks, and these reach a peak within 10 minutes. They are characterised by autonomy hyper arousal shown by some of the following symptoms:

– Palpitations

– Sweating

– Trembling or shaking

– Shortness of breath

– Feelings of choking or smothering

– Chest pain or discomfort

– Nausea or abdominal distress

– Dizziness

– Chills or hot flushes

– Parasthesias (Numbness or tingling sensations)

– Derealisation (Feelings of unreality)

– Depersonalisation (Feelings of being detached from oneself)

In panic disorder, patients tend perceive normal fluctuations in autonomic arousal as a stimulus that provokes anxiety, with the belief that these may signal the onset of a panic attack. During a panic attack, patients typically tend to report an irresistible urge to escape the location where the attack occurred and to avoid such situations in the future. Public settings are usually the most common location where panic attacks take place [e.g. queues, public transport, shopping mall, etc] and acute autonomic arousal is only alleviated upon escape from these places or situations – hence secondary agoraphobia often develops when the patient fears leaving the safety of their homes in case of panic attacks occurring in public settings.

[5] Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tends to occur after a catastrophic trauma such as a terrorist attack, an armed combat/robbery, a natural or man-made disaster, a serious accident that was perceived to be potentially life-threatening for oneself or others, torture, child abuse or rape.

PTSD is mainly composed of:

– Recurrent intrusive traumatic memories

– Intense anxiety in response to these memories and ongoing hyper arousal in anticipation of their recurrence

– attempts to regulate anxiety and hyper arousal by avoiding cues that trigger traumatic memories and attempts to suppress these memories when they intrude into consciousness (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Ehlers, 2009; Friedman, 2009; World Health Organization, 1992).

Recurrent, traumatic memories include flashbacks, nightmares, or repetitive trauma themed play in the case of children, and these occur in response to internal (psychological) or external (environmental) cues that symbolise the traumatic event or aspects of it. Since patients with PTSD tend to anticipate the recurrence of traumatic memories, they experience chronic hyper-arousal which may in turn lead to difficulties in concentration, sleep difficulties, hyper-vigilance and irritability. In PTSD, the attempts to suppress traumatic memories and the avoidance of trauma-related situations may turn out to be unsuccessful, when such a scenario occurs, the PTSD person generally experiences an increase in the frequency and intensity of past traumatic memories. Emotional numbing is also quite common in chronic cases due to the frequent attempts to keep the trauma-related memory out of consciousness – this eventually leads to the inability to recall the traumatic memories. To some this may seem like a solution but the cost is excessive since emotional numbing does not only result in the exclusion of trauma-related emotions such as anxiety and anger out of consciousness, but also tender feelings such as love and joy – which cease to be experienced by the patient.

PTSD may also lead to a subjective sense of foreshortened future to the patient and this may also be accompanied by limited involvement in his/her usual activities.

[6] Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is generally characterised by distressing obsessions and compulsive rituals that reduce the anxiety associated with those obsessions [like 2 opposing forces] (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Matthews, 2009; World Health Organization, 1992; Zohar et al., 2009). Obsessions are stereotyped thoughts, impulses or images that are recurrent and persistent. These cause serious anxiety to the patient since they are experience as senseless, uncontrollable and involuntary, and are linked to issues such as obscenity [this does not mean that healthy people with normal sexual feelings in healthy relationships have OCD], violence and danger [for e.g. some people suffer from irrational fears of the possibility of a catastrophe occurring unless symmetry or order is maintained, or there may be fears of losing control and violently raping or assaulting others, or fears of contamination [hygienic].

These compulsions are ritualistic and repetitive accompanied by stereotyped behaviours such as hand washing, ordering and checking or mental acts such as repeating words silently [which some patients feel compelled to do to regulate the anxiety caused by the obsessions], counting or praying [this should not lead to the belief that all people with faith in God suffer from OCD]. Compulsions are generally excessive attempts or unrealistic ways to avert imagined dangers entailed by these recurrent obsessions that are debilitating and are usually recognized as pointless while repeated attempts are made to resist them [once again this seems to be linked to the unconscious yet active component of mental activity and yet again leads us to Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan].

Clinical Features of Anxiety Disorders

The 6 anxiety disorders listed above are classified into the domains of Perception, Cognition, Affect, Arousal, Behaviour and Interpersonal Adjustment. In regards to perception, the disorders vary in the classes of stimuli that elicit the anxiety in the patient.

i)Perception

In cases of Separation Anxiety, the separation itself is the stimulus. Where phobias are the condition present, it is specific creatures [e.g. animals], events [e.g. injury], or situations [e.g. meeting new people] that trigger the anxiety. With Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD], the interpretation of multiple aspects of the environment end up being interpreted as potentially threatening. Panic disorder is characterised by somatic sensations of arousal such as tachycardia being perceived as threatening since they are treated as the signals that lead to full-blown panic attacks. In people with PTSD external and internal cues that bring back memories of the trauma that led to the condition elicit anxiety. In Obsessive Compulsive Disorders (OCD) stimuli that evoke obsessional thoughts elicit anxiety [e.g. potentially dirty environments or situations may give rise to obsessional ideas about hygiene and cleanliness, and anxiety about contamination.

ii)Cognition

It is important to note that in all 6 of those listed anxiety disorders, that the central organizing theme around cognition is “detection and/or avoidance of danger”. In children with Separation Anxiety there is the irrational belief that the caregivers or parents will be harmed if the separation occurs. In people affected by Phobias there is a constant fear of being harmed by either the feared object or creature, or being in the feared situation [e.g. being bitten by a god – in the case of Dog Phobia OR being negatively judged by meaningless strangers that have no connection or impact on the life of the patient in the case of Social Phobia]. As for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), patients tend to catastrophize about any features of their environment [e.g. fears of their house being burnt down, or that they will be the victim of a car crash, or punishment for some wrongdoing, they will be forsaken by those they consider as friends, and so forth – they also believe that their worries are uncontrollable. In Panic Disorder, there is the belief that more panic attacks are imminent and that they might be fatal to the patient. In many cases secondary agoraphobia also develops as they individual develops the belief that remaining in the safety of their homes might lower the probabilities of suffering from a panic attack. As for PTSD, there is the belief that as long as the intrusive memories of the trauma are forced out of consciousness, the danger of re-experiencing the intense fear, distress and horror associated with the traumatic event that led to the condition of PTSD can be avoided. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) generally leads to obsessions mainly concerned with dirt and contamination; catastrophes such as fires, illness or death; symmetry, exactness and order; religious scrupulosity; disgust with secretions and bodily wastes [e.g. urine, saliva or stools]; lucky or unlucky numbers and extreme, wild, violent and even dangerous sexual thoughts [risk-taking] – the neutralisation of the threat posed by specific obsession-related stimuli is believed to be achieved through being engaged in specific rituals.

iii)Affect

In all 6 of the mentioned anxiety disorders affective states generally follow the beliefs about threat and danger, and these are characterized by feelings of uneasiness, restlessness and tension. In the case of OCD, outbursts of anger may occur if the patient is restricted from executing his/her compulsive rituals or if compelled to approach the feared stimuli; and in children with Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) may display aggressive tantrums if compelled to stay in school without their caregivers or parents. In Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), on top of the affective experiences of tension and uneasiness, emotional numbing arises from repeated attempts to exclude all affective material from consciousness.

iv)Arousal

The pattern of physiological arousal varies depending on the frequency of contact with the feared stimuli. In Separation Anxiety Disorders (SAD), hyper-arousal only occurs when separation is anticipated or imminent. In the case of Specific Phobias hyper-arousal only manifests in the present of the feared object or animal. In General Anxiety Disorder (GAD), a pattern of ongoing hyper-arousal can be observed, while in Panic Disorder and PTSD it is moderate followed by brief episodes of extreme hyper-arousal – these occur during attacks in Panic Disorder and when memories of the traumatic event intrude into consciousness in PTSD. In the case of OCD, specific cues related to the obsessions evoke acute and intense episodes of arousal.

In somatic symptoms the extent to which physiological arousal finds expression varies, for e.g. recurrent abdominal pain and headaches are quite common in Separation Anxiety. Sleep problems also occur in most Anxiety Disorders. In Panic Attacks it is also common to notice full blown attacks with sweating, feelings of choking or smothering, shortness of breath, trembling, nausea, dizziness, chest pains, hot flushes or chills, parasthesias, depersonalization or derealisation.

v)Behaviour

All Anxiety Disorders are characterized by avoidance behaviours, and in Specific Phobia, avoidance may even lead to a constriction in lifestyle [using an Injury Phobia as example, the patient may refuse to take part in any form of physical activity [e.g. sports] or ride a bicycle]. In other cases, the patient sometimes become house bound due to his compulsive avoidance, and this generally occurs in Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder and PTSD. In those with PTSD, the use of alcohol or drugs to alleviate negative affect and suppress traumatic memories is quite common; and in OCD the patients generally engage in compulsive rituals in a desperate effort to regulate their anxiety associated with obsessional thoughts [it may be fair to note the relation between the Anxiety [as the Signifier] and the Obsessional Thoughts [as the Signified] in a Lacanian perspective here to point out the logic behind the flamboyant Frenchman’s model of Mental Activity based on Freud’s initial Topological Model – the Unconscious, the Preconscious and the Conscious]. These compulsions in OCD genereally include washing, repeating a particular action, checking, removing contaminants, touching, ordering and collecting.

vi)Interpersonal Adjustment

All 6 Anxiety Disorders affect interpersonal adjustment in a precise manner. In cases of Simple Phobia, interpersonal difficulties arise only in those situations where the individual does not conform or co-operate with normal activities [deemed social] so as to avoid the feared stimuli [e.g. a brief episode of marital conflict may occur if a husband refuses to enter an elevator at a shopping mall because of his claustrophobia]. Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Panic Disorder (PD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) sometimes prevent young people from attending school or adults from attending work, and in all those situations friends or family relationships may be seriously compromised. In the case of OCD peers or relatives may sometimes attempt to reduce the sufferer’s anxiety in participative actions in the compulsive rituals or in other cases, they may also exacerbate the anxiety by punishing the patient for his or her compulsive behaviour. In extreme cases, these compulsions can become so extreme that the affected person becomes constricted.

Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Course of Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety Disorders are the most common types of psychological disorders, and the lifetime prevalence rate in adults in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication was 28.8% (Kessler et al., 2005). There is a consensus that Phobias are the most prevalent anxiety disorders and OCD is the least prevalent across a wide range of epidemiological studies (Kessler et al., 2009; Furr et al., 2009). For Phobias, lifetime prevalence estimates range from 6% to 12%, whereas those with OCD fall below 3%. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) has a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 6 %, whereas Panic Disorder in adults and Separation Anxiety in children range from 2% to 5%. In National representative samples, the prevalence of PTSD ranges from less than 1% or 2% in Western Europe to almost 8% in the US. The great variability is believed to be due to the fact that PTSD rates depend on the prevalence and traumatic exposure within specific locations geographically and the vulnerability of the populations within these countries to developing PTSD – in populations exposed to terrorism the prevalence is 12% – 16% (DiMaggio & Galea, 2006).

In people suffering from Anxiety Disorders, there is also a high risk of comorbidity [i.e. other anxiety disorders may also be present], and up to 1/3 of those suffering from Anxiety Disorders also suffer from another (Kessler et al., 2009) – they may also occur comorbidly with mood disorders in adults as well as children, substance use disorder in adults and adolescents and disruptive behaviour in young people/children (Furr et al., 2009; Huppert, 2009; Zahradnik & Stewart, 2009). In cases where substance misuse is also present, the use of drugs or alcohol is quite common in managing anxiety.

OCD is also present in a significant proportion of people with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. (Halmi, 2010).

We can observe a clear age and gender difference in the prevalence of Anxiety Disorders (Antony & Stein, 2009a; Furr et al., 2009; Kessler et al., 2009) and across most studies that are available, the modal age of the onset in Separation Anxiety Disorder and Specific Phobias is during the developmental phase in childhood [a stage pointed out by both great Western psychotherapists, Freud and Lacan, and also John Bowlby in his observational research on the development of attachment types in children at this critical stage of development], whereas that of anxiety disorders generally happens during adolescence or adulthood. In both adults and children, there is a tendency for more females to suffer from Anxiety Disorders than males, with the exception to this balance being for OCD which has a similar number men and women suffering from the condition although it is the rarest of anxiety disorders.

Anxiety Disorders tend to show a recurring episodic course with a gradual reduction in prevalence over the course of the life cycle (Kessler et al., 2009). It is also worthy to note that most children with anxiety disorders do not grow up to be adults with anxiety disorders or depression, however most anxious adults do have a history of childhood anxiety disorders. There are a number of risk factors associated with Anxiety Disorders and these include anxiety disorders or psychological disorders in the direct genetic network, an inhibited temperament of behaviour, neuroticism as a trait of personality, a personal experience of psychological problems, a history of over-controlling or critical parents, a history of conflict and violence and a history of stressful life events (Antony & Stein, 2009b; Pine & Klein, 2008). In the scenario of Anxiety Disorders, a behaviourally inhibited temperament is generally the tendency from birth – to become nervous and withdrawn from unfamiliar situations and stimuli. Neuroticism is a trait of personality that gradually develops over the life-span, and it is characterized by the tendency to escape negative affect and includes hostility, anxiety and depression in its manifestations.

In those suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) the additional factors that increases the risk for development include the severity of the trauma, high-life stress following the trauma, low socio-economic status, low support [from friends or those considered as friends], low intelligence and low educational level (Ehlers, 2009; Ozer et al., 2003). In PTSD, dissociative experiences tends to refer to abnormalities of perception, memory or identity such as derealisation [seeing the world as dream-like], depersonalization [seeing oneself from an external perspective or inability to recall important information]. In the case of parents with PTSD, their children are also at a higher risk of developing the disorder (Pine & Klein, 2008).

_____________________________________

Part 3 of 5 | Depression

Source: World Health Organisation

The states of being happy or sad are adaptive feelings, and many behaviours that lead to happiness among human beings, such as socializing [with the people that matter to the subject], becoming completely absorbed in productive work and developing longstanding friendships that are meaningful around values and loyalty, are important not only for the emancipation of the individual but also for a harmonious and functional society that embraces the “humane” qualities of mankind in all its creative aspects.

Sadness on the other hand is a psychological state commonly preceded by loss [of various kinds, which may range from material objects to valued relationships or abilities/skills and status related to them through accident or disease or other situations], and it is a negative feeling which may also be adaptive, in a sense that it is a reminder to most people [at least for those who are NOT philosophically oriented / cultured or have an understanding of values and loyalty in interpersonal relationships], that valued things or people need to be taken care of if they do not want to lose them in the future, especially the common volatile brain [i.e. the basic Darwinian instinct-guided average brain that lacks reflective abilities, reasoning skills, intuition and insight, while also failing to realises or understand the motivation behind its behaviour until matters have taken a disastrous course]. Sadness is also a way of signalling to others that we as human beings also need care and elicits [to most psychologically healthy human beings with a theory of mind] support that soothes our emotional pain – this is what makes us a superior breed of primates, i.e. our ability to reason and evolve with emotions as a propulsive form of energy for both individual and group, like Alexandre Dumas put it, “Un pour tous et tous pour un!” [French for “One for all and all for one!”].

Some extreme states of mood such as depression and mania are less adaptive than happiness and sadness; and it is now commonly known that during periods of hypomania or mania some patients suffering from Bipolar Disorder [which is characterized by episodes of mania and depression] produce highly creative artistic work (Silvia & Kaufman, 2010). This should not lead us to the conclusion that ALL creative people with extreme ways of exploring and expression their emotions through art suffer from Bipolar Disorder. But for those who do suffer from Bipolar Disorder and produce creative work, this highly valued asset comes at a price, since these individuals generally involve themselves in high-risk behaviours that come with the possibility of severe dehydration and exhaustion during manic episodes.

Seasonal Affective Disorder [or Winter Depression, its colloquial name] is a condition that is believed to be linked genetically to our cave-dwelling ancestors from the prehistoric era, who may have hibernated – an adaptive behaviour for the ancestors. However, in the world of today, depression does not seem to serve any adaptive function, and despite this, it remains a highly prevalent condition that affects up to 25% of the population (Kessler & Wang, 2009); because of this prevalence the main focus of this section will be on Major Depressive Disorder.

Share of the population reporting that they had chronic depression / Source: EuroStat

It is quite fundamental to grasp that depression is not simply “feeling sad”, as Major Depressive Disorder is an ongoing condition characterized by episodes of low mood and loss of interest in pleasurable activities along with other symptoms such as poor concentration, fatigue, pessimism, suicidal thoughts, and sleep and appetite disturbance. Depression is a serious public health concern because it radically decreases the quality of life of those affected, is a huge economic burden in terms of reduced productivity [and lack of creativity] among the national work force, and it also has adverse effects on the mental health and adjustment of the children of the depressed people (Garber, 2010; Kessler & Wang, 2009). This section will focus on the clinical features, epidemiology, risk factors and course of depression [suicidal risks will also be discussed].

Clinical Features of Depression

Severity

Depression can be classified as mild, moderate to severe, depending on the degree of impairment

Melancholia

In regards to somatic or melancholic features, in severe depression where there is a loss of pleasure in all activities [known as anhedonia] and a lack of reactivity to pleasant stimuli along with diurnal variation in mood and sleep and appetite disturbance, we tend to qualify such episodes as having melancholic features. Historically [please take note that this is not the case anymore], there was an ongoing view that these symptoms reflected “endogenous”, a genetically determined and biologically based form of depression, as different to a “reactive” depression arising from exposure to stressful life events and environmental adversity (Monroe et al., 2009).

However, the difference between these 2 forms of depression was not supported by empirical research, which instead shows that ALL episodes of depression are preceded by stressful life events, and that in any given scenario, we tend to have a combination of genetic vulnerability and environmental adversity that contribute to the development of depression (Parker, 2009).

Psychotic Depression

When mood disrupting delusions and hallucinations are present, depressive episodes are described as having psychotic features. Mood-congruent delusions are generally firmly held beliefs that are extremely pessimistic in nature and that have no basis in reality [illogical and cannot be explained and justified; for e.g. that a completely innocent individual is guilty of many wrongdoings and deserve to die. Mood-disrupting hallucinations in depression are generally auditory and sometimes involve the hearing of voices in a complete absence of any form of external stimuli [uncontrolled and unimagined and ongoing for months], which has negative advices to the sufferer [e.g. You are a failure, you are guilty of wrongdoing, or evil].

Among children, adolescents and adults, there has been a range of clinical features identified through both clinical observation and empirical research (e.g. Bech, 2009; Brent & Weersing, 2008; Gotlib & Hammen, 2009; Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009a). Common clinical features of depression tend to affect the domains of cognition, perception, mood, somatic state, behaviour and relationships. Loss is once again a main thematic feature in depression as pointed out by Psychoanalytic Theories [loss of any kind, e.g. material, emotional, relationship, valued attribute due to sickness/accident, health, etc], and clinical features may be linked to those different domains of mental life.

Perception

In regards to perception, depressed individuals who have suffered some form of loss [internal or external] tend to perceive reality and the world as one where further losses are possible, and individuals who suffer from depression also selectively attend to negative stimuli and features in the environment. This leads them to engage in further depressive cognitive patterns in their thoughts processes and unrewarding behavioural patterns which amplify their depression’s severity – in cases of severe depression, mood-congruent auditory hallucinations are often reported. Hence, depressed people or people with depressive personality traits tend to come across as repulsive and despicable because of their obsessive disposition to only perceive the negative side of everything and every situation that life has to offer [note: this is different to constructive criticism which is normally for a purpose and comes with systematic reasons for enhancement]. Psychologists tend to go with the assumption that such severe perceptual abnormality is present only when patients report hearing harsh critical voices or containing depressive contents [as mentioned above]. These auditory hallucinations are also present in schizophrenia, however they are not always mood-congruent like in depression.

Cognition

Depressed patients tend to describe the world and the fabric of reality of their subjective experience in negative terms, this also include descriptions of themselves and their abilities [e.g. occupational and social accomplishments] – this negative evaluation is often portrayed as guilt for not living up to the standards [they set themselves based on their ‘perceived’ abilities] or for letting others down. They sometimes perceive their direct environments [peers, network, family, work colleagues or school/university] as hostile, apathetic, critical and unrewarding. The future is also described in very bleak terms by those suffering from depression, and they also report little if any hope that matters will improve. When extreme hopelessness is reported is it usually accompanied with excessive guilt for which the patients believe they should be punished – suicidal ideas and intentions may also be declared. In depressive delusional systems, extremely negative thoughts about the self are generally reported with the world and their future entangled in them.

Besides the content and thoughts being incredibly negative and bleak, depressed patients also tend to display concentration problems and logical errors in their thinking. These mistakes in reasoning are also characterized by a tendency to maximise the significance of negative events and minimize the significance of positive ones. Depressed patients also suffer from memory problems and struggle to remember happy events but instead have global over-general autobiographical memories about both positive and negative events. In addition to these, this category of patients also suffer from concentration, attention and decision-making problems that in turn give rise to difficulties managing leisure activities requiring sustained attention and academic or occupational responsibilities.

Affect

The impact on the patient’s affect tends to lead to low mood, and diurnal variations in mood and anhedonia. The depressed mood is usually reported as a feeling of sadness, loneliness, emptiness and despair. Diurnal variations in mood is usually quite common in severe cases of depression, with the patient’s mood generally being worse in the morning or after waking up. In cases of major depression, as a person moves from mild to moderate to severe depression, the increasing number of symptoms along with the intensity can also lead to intense anxiety. Generally, fears are experienced in the form of “Will this get worse? Am I stuck in this living hell forever? Will I ever be myself again? Will I be able to prevent myself from committing suicide to escape? Irritability is also a characteristics of depression, with the patient sometimes expressing their anger at the source of their loss [e.g. anger at a deceased one for abandoning the grieving person or sometimes at the health professional for not being able to alleviate their depressive symptoms].

Somatic State

The changes in the patient’s somatic state associated with depression include the disturbances of sleep and appetite, the loss of energy, failure to make age-appropriate physiological growth, weight loss, pain symptoms and a loss of interest in sexual activities. Commonly, depressed people struggle to find sleep and eat insufficiently due to their poor appetite; these symptoms are known as vegetative features. The sleep disturbances in depressed people generally involve problems trying to sleep, wakefulness at night or early-morning sleep disruption. Other symptoms such as racing thoughts and engaging in depressive rumination while unable to sleep is also quite common. In atypical cases of depression, patients may sometimes oversleep due to a constant feeling of exhaustion and consume excessive food due to an increased appetite or due to the feeling that eating may temporarily reduce their distress.

Medically unexplained chest, abdominal and back pain along with headaches are some of the additional features of depression. In some cases the pain symptoms are some of the first signs that would be reported to the doctor and it is only when the medical investigations of these symptoms turn out to be negative that depression is suspected to be the cause. All the somatic symptoms mentioned are consistent with research: dysregulation of neurobiological, endocrine and immune functions is associated with depression and the sleep is also affected.

Behaviour

Depressed patients are characterized behaviourally by the reduced and slow activity levels [psychomotor retardation] that they display, and are often helpless [without any control over their abilities] about their inability in getting involved in activities that could have helped their condition by bringing a sense of achievement or connectedness to meaningful [those chosen by the individual as a person with significance to him/her – note that it is a choice] people in their life. In rare cases some individual become house bound and immobile; such a condition is known as depressive stupor.

One of the major risks of depression is self-harm [a clear distinction is made between non-suicidal deliberate self-harm and suicidal behaviour]. In non-suicidal tendencies, patients may cut or burn themselves to distract themselves from the depressive feelings. In some cases, some have taken non-lethal overdoses to elicit attention and care from their close ones or to simply gain admission to hospital and remove them from the stressful situations that may have been amplifying their depressive symptoms.

Relationships

Depressed patients generally report a deterioration in their relationships with a range of significant figures in their lives from a wide range of environments [from professional to personal], and describe themselves as lonely, unable or unworthy to take steps to try and engage in some form of contact with others. Surprisingly, when the depressed attempt to overcome their loneliness by talking to others, they tend to come across as repulsive, unpleasant and draining through their depressive behaviour, pessimistic belief and sometimes arrogant narcissistic talks, this drives away those they interact with.

Video: Comment faire avec les gens frustrés ? – Benoit Zwick (2019)

Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Course of Depression

The most common mood disorder is Major Depression, and it has a lifetime prevalence rate of 6 – 25% in international community studies (Kessler & Wang, 2009). In the US National Co-morbidity Survey Replication the lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV Major Depression was 16.6% (Kessler et al., 2005). It is good to note that Depression is less common among pre-pubertal children than adolescents and adults (Brent & Weersing, 2008). Among children the number of boys to girl with depression is equal, however this changes in adolescence and by adulthood; compared with men, about twice as many women have depression (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009b).

In most cases of depression, there are many comorbid disorders also present. In the US, National Comorbidity Replication Survey, 59% of depressed patients suffered from comorbid anxiety disorders and 24% had comorbid substance use disorders (Kessler & Wang, 2009). Depression also tends to follow a chronic relapsing course, with up to 80% of people suffering from recurrent episodes, and it has been found that the median duration of episodes in community samples typically lasts for about 5-6 weeks. In clinical samples depressive episodes tend to last for about 5 to 6 months; the majority of cases however recover within 1 year and about half of patients continue to suffer from fluctuating residual symptoms between those depressive episodes; and for less than 10% of patients, recovery does not occur and chronic depressive symptoms persist and most cases relapse within 5 years (Angst, 2009; Boland & Keller, 2009).

During treatment, as more depressive episodes occur, we tend to notice a decrease in inter-episode intervals and a reduction in the amount of stress required to trigger the onset of further depressive episodes, an issue related to Stress Theories (Boland & Keller, 2009).

NOTE: Stress theories propose that individuals develop depression following exposure to stress. The diathesis- stress theories propose that depression only follows after exposure to stress in people who have specific biological or psychological attributes that render them more vulnerable to stressful life events, and the most vulnerable require the least stress to trigger depression (e,g., Joiner & Timmons, 2009: Joormann, 2009; Levinson, 2009). On the other hand, Stress-generation theory proposes that people with certain personal attributes inadvertently generate excessive stress, which in turn leads to depression (Liu & Alloy, 2010)

The risk factors for depression include a family history of mood disorders, female gender, low socio-economic status involving educational and economic disadvantage, and adverse early family or institutional environment, the depressive temperament, a negative cognitive style, deficits and self-regulation, high levels of life stress, and low levels of support from meaningful others (Garber, 2010; Hammen et al., 2010).

Risk factors for recurrent major depressive episodes identified in the US collaborative depression study of 500 patients, include a history of three or more prior episodes, comorbid dysthymia (often known as Double Depression), comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders, long duration of individual episodes, poor control of symptoms by antidepressant medication, onset after 60 years of age, the family history of mood disorder, and being a single female (Boland & Keller, 2009).

Four small category of people who suffer from depression, deficits the visual processing of light and the season of the year are risk factors for depression (Rosenthal, 2009). These people, who experience regularly recurring depressive episodes in the autumn and winter, with remission in the spring and summer, are generally considered as suffering from Seasonal Affective Disorder. These patients develop symptoms in the absence of adequate light and respond positively to enhanced environmental lighting, often referred to as “Light Therapy or Treatment” (Golden et al., 2005).

In community samples about 3.4% of people with major depressive disorder commit suicide; the rate in clinical samples about 15%; about 60% of completed suicides (studied by psychological autopsy) had suffered from depression (Berman, 2009).

_____________________________________

Part 4 of 5 | Schizophrenia

Before covering the topic of schizophrenia, it is important to take note that the condition is commonly confused to refer to another condition that involves split-personalities, and this is mostly a trend that lives in the world of pop culture and Hollywood. About 40% in the UK equated split or multiple-personality with schizophrenia in a National Survey (Luty et al., 2006). However, after covering this section, we hope that the confusion will be cleared since schizophrenia does not refer to conditions that involve split-personalities [the closest scientific equivalent to this state of being, is a condition known as Multiple Personality Disorder or Dissociative Identity Disorder and are both not as debilitating as schizophrenia with treatment being much more effective].

Schizophrenia refers to a collection of seriously debilitating conditions characterised by positive and negative symptoms in this organisation (Mueser & Jeste, 2008).

Delusions and hallucinations are the principal positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Delusions are strongly held, unfounded, culturally alien beliefs. For example with persecutory delusions, individuals may believe that a group of people conspiring to harm them [this should not lead us to believe that a healthy person with a suspicion caused by the critical analysis of a person or group of people is deluded and is schizophrenic – remember that human beings have individual personalities too]. Hallucinations on the other hand involve experiencing sensations in the absence of external stimuli [e.g. with auditory hallucinations – which are the most common type in schizophrenia – people reported hearing voices that others cannot hear].

The negative symptoms of schizophrenia include flattened affect, alogia and avolition. In the case of flattened affect, the emotional expression of the patient is limited, and with alogia there is an impoverished thought that is inferred from the patient’s speech. Short brief and concrete replies are given to question [this is referred to as poverty of speech], or in some cases speech production is normal but it conveys little meaning and information due to repetition, or being overly abstract [referred to as poverty of content], or being too concrete. When patients suffer from avolition, a lack of goal directed behaviour can be observed. The negative symptoms generally give rise to a restricted lifestyle involving little activity, little social interaction with others and little emotional expression – disorganisation may also affect both speech and behaviour [disorganised, illogical, incoherent, speak are the signs of an underlying formal thought disorder]. Disorganised catatonic behaviour is usually characterised by the complete absence of spontaneous activity or excessive purposeless activity.

Schizophrenia is a debilitating and re-occurring condition that comprises the capacity to carry out normal activities, and also consists of incomplete remission between episodes. (Hafner & der Heiden, 2008). Symptoms of schizophrenia typically appear in late adolescence or early adulthood, wax and wane over the life course, and have a profound long-term effect on patients and sometimes their families.

Schizophrenia is considered to be the most debilitating of all psychological disorders, since it affects the patient’s capacity to live independently, make and maintain satisfying and enduring relationships, engage in family life, parent children effectively, work productively and enjoy leisure activities. Rates of unemployment, homelessness and imprisonment are very high among people with schizophrenia, although just under 1% of people suffer from schizophrenia, the World Health Organization has rented as second only to cardiovascular disease in terms of overall disease burden internationally (Murray & Lopez, 1996).

Despite these unattractive facts, the scientific advances in our understanding of schizophrenia, along with advances in both psychological and pharmacological approaches to treatment, making it increasingly realistic for people who suffer from schizophrenia to live far more productive lives than were previously possible (Mueser & Jeste, 2008).

Case Example of Schizophrenia

A young man, named Julian was referred for assessment and advice by his doctor. Since returning to his rural home after studying in London for one year, his parents started to worry about his state because of his strange behaviour. After failing as exams, the patient said that he had to ”sort his head out”. Since his return, the parents had noticed a lack of concentration along with incoherent speech during his conversations which happen most of the time – his behaviour was also erratic and unpredictable.

The parents concern grew when Julian suddenly went missing a few weeks prior to the referral. After hours of searching, he was found about 55 Km from their home, dehydrated, exhausted and dressed only in sport shorts, singlet and running shoe. After enquiry, the latter developed the belief that a secret mission in the East had to be undertaken by him; and as he started jogging in the morning, he headed eastwards towards the rising Sun. He even planned to jump onto the car ferry when he reached the coast, across the sea over to Holland, and continue east towards India in his secret mission [reminiscent of a James Bond episode].

Since the episode, Julian has spent much of the time in his room muttering to himself, often becoming quite distressed, and when his parents spoke to him they found it hard to make any sense out of his words.

Family History

Julian was the 19-year-old son of a prominent farmer in a rural English village where the whole family lived in a large amount on an extensive estate. The farm was managed by the patient’s father; who had a traditional authoritarian manner and a positive, if distant, relationship with Julian. While he was incredibly worried about Julian and to the search for him, once the latter was found, the father returned to work unless the care of his son to his wife.

The mother was an artist who dressed flamboyantly, behaved in a theatrical manner and held century, unconventional beliefs [e.g. Conspiracy theories about many issues, was interested in eastern mysticism and believe that faith healing and alternative medicine were preferable to traditional Western medicine]. These characteristics of a personality along with her beliefs affected her treatment of Julian after the ”Running East” episode, where she engaged the latter in intense conversations about mystical meaning of the psychotic experiences that led to him trying to make his way to India on foot. Rather than taking Julian to the accident and emergency department of the local hospital for assessment, she brought him to a feeler and then than homeopathist. It was only of these interventions failed to our view the distress that she took Julian to the doctor, who made the referral to the community mental health team. In the preliminary assessment that was conducted with Julian and both of his parents, the mother responded to the son with intense emotional over involvement (an index of high expressed emotion associated with a relapse in schizophrenia; Hooley, 2007).

With regard to the extended family, according to parents there has never been a family history of psychological disorder. However some members of the mother’s well-to-do family were fairly eccentric and odd, especially her brother, Sedric, and her uncle, William Jr. Williams eccentricities led him into serious conflict with his father, and Sedrick’s odd behaviour underpin his highly conflictual, childless marriage.

Developmental history

Julian on a family farm and went to the local school, his development was what most people would call normal. His Academy former school was above average and he had many friends in his local village, and was a popular child and adolescent who also excelled at cricket. At 18 years old before going to university London, he had no psychological problems.

His first term at college was successful academically and socially, however, the occasional experimental cannabis use that had begun the summer before going to college turn to a regular use once Julian moved to London. During his time at university, the patient also experimented with LSD on a few occasions. In the final term of his first year at college, Julian developed intense fear of exam failure. Other symptoms quickly followed such as difficulty studying effectively and sleeping problems. Julian stopped attending classes regularly and spend more time alone, and was relieved to return home after sitting as exams. Once home he was described as quiet and thought during most of the time prior to the “running East” episode.

Presentation

Julian presented with symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech and anxiety. At the very start the patient was very reluctant to be interviewed because he believed he had urgent business to attend to in Holland and further afield in India. He also showed signs of being anxiously distressed throughout the interview, explaining that his path was to the east and believed he was being called there by an unknown source. He firmly believes this because of a sign he had seen while out jogging on the morning of the enigmatic “running East” episode. The way in our God will record the sunlight and cast a shadow on the red barn against which it was leaned made a distinctive pattern, which to him meant a special sign indicating that he should go East, first to Holland and then all the way to India. Upon questioning this idea, a clear authoritative voice said that he should leave at once.

At this point in his narrative, stopped mid-sentence and displayed thought blocking, and will strive the topic he was talking about. Upon being asked to continue his story, he began to giggle, and when questioned about the reason behind his amusement, Julian declared to have heard someone say something funny. Julian then spoke about a number of unrelated topics in an incoherent way before experiencing thought blocking again.

Later he expressed the desire to leave soon because people will try to prevent him, as he had heard them plotting about this the day before, and also declare that they had tried to put bad ideas into his head [which he described as frightening]. He was also frightened by periodic sensations that everything was too loud or too bright and coming at him, declaring “it was like doing acid [LSD] all the time… a really bad trip.”

Formulation

In Julian’s case he presented with auditory hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder, anxiety and a significant deterioration in social and occupational functioning which had been present for more than 1 month [symptoms consistent at the time of this essay with a diagnosis of Schizophrenia]. The patient also showed a complete lack of insight and was unable to understand that the voices being heard were hallucinations and that the delusional beliefs were unfounded. Among the major precipitating factors were the experience of recent exam pressure and his transition from living at home to living in London at attending college. The principal predisposing factors were possible genetic vulnerability to psychosis and a history of hallucinogenic drug use.

His psychological condition was maintained by what was likely to be an excessive level of maternal expressed emotion characterised mainly by emotional over-involvement. His delusions were also reinforced by the mother since the latter engaged Julian in long and draining conversations about them. The protective factors in this case were godo premorbid adjustment and a strong family support for the boy.

Treatment

The treatment plan included antipsychotic medication and family will to reduce parental expressed emotion, with an initial brief period of hospitalisation. Julian did recover from his first psychotic episode, and his hallucinations and delusions decrease considerably with medication. Through family Psycho-education, parents develop understanding of this condition and of the requirement of a “low-key” approach to interacting with the boy as he recovered.

However some obstacles were encountered in Julian’s recovery, since he disliked the side effects of the medication, especially the weight gain and reduced sexual drive/function, and so had poor medication adherence – depression also manifested during the remission, when Julian came to realise about the many losses that followed his condition. He was unable to pursue his university studies and thus, could not continue the law career he had dreamed of. He also experienced difficulties in maintaining friendships or to commit to engaging on a regular basis in physical exercises or sports. When his mood was low, Julian would smoke some cannabis to lift his spirits.

The mother found it very difficult to accept the diagnosis of Schizophrenia and continued to hold the belief that his psychotic symptoms were linked to some spiritual or mystical explanation. She even sometimes declared that she thought of her son not as an ill young man, but a gifted seer or a “chosen one” [based on no rational explanation or series of events], and often engaged Julian in intense, distressing conversations about these issues. In the years that followed his initial assessment, poor medication adherence, ongoing cannabis use [which the patient could not tolerate unlike some other users] and exposure to high levels of intrusive parental emotions led Julian to relapse more often than might otherwise have been the case.

Clinical Features of Schizophrenia

A range of clinical features have been identified and associated with Schizophrenia though research and clinical observations (Mueser & Jeste, 2008). The generally concern the domains of perception, cognition, emotion, behaviour, social adjustment and somatic state.

Perception

At the perceptual level, patients suffering with schizophrenia generally describe a breakdown in perceptual selectivity, with difficulties focusing on essential information or stimuli to the exclusion of accidental details or background noise. Most aspects of the environment seem to be salient, however, the inability to distinguish between figure and ground is a serious problem to the sufferer. During an acute psychotic state, internal stimuli such as verbal thoughts are experienced as auditory hallucinations that have the same sensory quality of the spoken word.

Auditory hallucinations can sometimes be experience as extremely loud thoughts, or as thoughts being repeated by another person aloud (thought echo), as voices speaking inside the head or as voices coming from somewhere in the outer environment. The auditory hallucination may occur as third person making comments on the patient’s action, as a voice speaking in the second person directly to the person, or as two or more people talking or arguing – the effect did may also perceive voices to vary along the number of dementia [may be construed as benign or malevolent, controlling or impotent, or knowing or knowing little about the patient, who may sometimes feel compelled to the demands of the voice or not.

When hallucinations are perceived to be malevolent, controlling, all-knowing, where the individual affected feels compelled to obey the demands of the voice, the situation is deemed to be far more distressing than those who do not have these attributes. While auditory hallucinations are the most common features in schizophrenia, hallucinations may okay other sensory modalities too. Somatic hallucinations also often occur in schizophrenia, with many cases including reports of electricity in the body or the feeling of something crawling underneath the skin [these may be qualified as delusional interpretations. For example, a patient reported that the television was activating a transmitter in her pelvis and she could feel the electricity from this closing insects to grow and move around under the skin. Visual hallucinations [seeing visions] are relatively rare in schizophrenia very common in temporal lobe epilepsy.

Cognition

At the cognitive level, delusions are the most common cognitive clinical feature of schizophrenia, and are false, idiosyncratic, illogical and stubbornly maintained erroneous inferences drawn to explain unusual experiences, such as hallucination. [e.g. patient with auditory hallucinations where an authoritative voice commanding the latter to gather the children, was interpreted by the patient that she had been chosen by God to prepare all the children for the second coming of Christ]

Delusions may also arise from unusual feelings associated with psychosis. Persecutory delusions may develop from feelings of being watched. Delusions of thought insertion or thought withdrawal may develop as explanations for feelings that thoughts are not one’s own, or that one’s thoughts have suddenly disappeared. Factor analyses show that delusions fall into 3 broad categories:

Delusions of influence [including thought withdrawal or insertion, and beliefs about being controlled]; delusions of self-significance [including delusions of grandeur or guilt]; and delusions of persecution (Vahia & Cohen, 2008). Delusions may vary in the degree of conviction with which they are held [great certainty to little servant, the degree to which the person is preoccupied with them [the amount of time spent thinking about the belief], the amount of distress they cause.

Particular sets of the may comprise of a confused sense of self, particularly paranoid delusions with the patient holds the belief that they are being persecuted or punished for misdeeds, or delusions of control where there is a belief that their actions controlled by others [e.g. an unknown source or entity].