Charles Dickens’ Hard Times: “Have a heart that never hardens and a temper that never tires, and a touch that never hurts.”

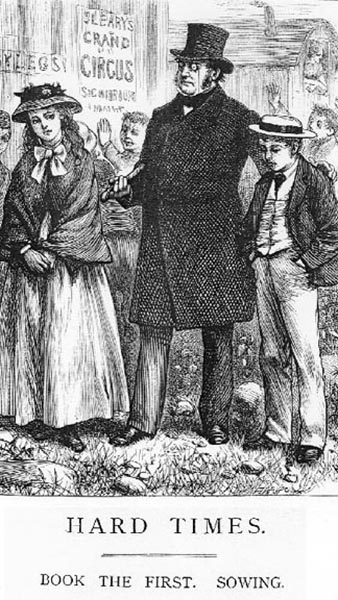

Hard Times is Charles Dickens’s tenth novel and follows his tradition as a social critic. Published in 1854, the novel is set in the fictitious town of Coketown during the Victorian industrial revolution. The story revolves around the constant struggle between fact and fancy, while Dickens treats us with characters that are comically characterized in multiple descriptive aspects in a – sometimes satirical – criticism of the social and economic pressure of his time. The story shows the impact of rigid aspects of life (upbringing, choices, circumstances and conditioning) on the characters that Dickens introduces in very dramatic situations – with images and dialogues in perfect tandem to deliver the near magical (surreal) effect he is known for treating his readers to. We will explore and analyse some of the key moments where Dickens uses characterisation before and after the climax in the dramatisation of his story and theme. The characters of Louisa, Gradgrind and Stephen Blackpool will be focussed on while particular attention will also be given to the rebellion against the utilitarian upbringing of a strict father, the blind preaching of fact, and the sad fate of a hard-working man struggling with a heavy drinking wife along with other tribulations of life.

Louisa is introduced to us in book one, “Sowing”, in Chapter 3, where she is caught peeping through the hole of a deal board by her father, Gradgrind. However, before the scene, we are introduced to Gradgrind and through Dicken’s physical portrayal of his character’s appearance, opinions and personality, we are dampened over the expected reaction of the strict father – especially over anything fancy – and in turn are more focussed on the reaction of the children. Louisa who will be focussed upon, is expected to have been fairly restrained throughout her upbringing; as before she is caught, Dickens gives an insight into the young Gradgrinds: “No little Gradgrind had ever seen a face in the moon; it was up in the moon before it could speak distinctly. No little Gradgrind had ever learnt the silly jingle, Twinkle, twinkle little star; how I wonder what you are! No little Gradgrind had ever known wonder on the subject, each little Gradgrind having at five years old dissected the Great Bear like a Professor Owen, and driven Charles’s Wain like a locomotive engine-driver”. (Dickens, 1995 p9)

While constantly following the theme of fact vs fancy, Charles Dickens uses a repetitive pattern with the “No little Gradgrind” adding a satiric sense which in turn adds to the feeling of mockery towards Gradgrind’s upbringing and his blind focus on facts. However, it also unveils early in the story, how the rigid conditioning of the hard man of facts was insufficient to completely smother Louisa’s inner sadness at not being able to enjoy the “fancy” side of life. Louisa described as “struggling through the dissatisfaction on her face, there was a light with nothing to rest upon, a file with nothing to burn, a starved imagination…” (Dickens, 1995 p11) comes as fairly expected in Dickens’ literature, while also giving us an insight in the children’s feelings; and judging from the outcome further in the story (where she nearly leaves Bounderby for James Harthouse), it tends to lead to the conclusion that the children have had to restrain so much (too much). Louisa’s short reply “Wanted to see what it was like” (Dickens, 1995 p11) gives us a hint about an air of rebelliousness about her character, a child eager to explore her emotions.

Another character, Thomas Gradgrind, whose role is pivotal to the plot; is also subjected to Dickens mockery. “’Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts, Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’” (Dickens, 1995 p3) Once again, the repetition and focus on “fact” through direct speech gives us a clear description of Gradgrind’s character; however, as the story opens with those lines, we are also exposed to further characterisation which comes in the form of very caricaturesque physical descriptions of the character: “The speaker’s square forefinger emphasised his observations by under scoring every sentence with a line on the schoolmaster’s sleeve. /…the speaker’s square wall of a forehead, which had his eyebrows for its base, while his eyes found commodious cellarage in two dark caves, overshadowed by the wall.” (Dickens, 1995 p3) Both, the speech and the near surreal and comical physical description given by Dickens add to the dramatic effect accompanying Gradgrind as the story progresses. We are bound to tag these characteristics to his character from start to finish. Furthermore, the twist near the end is also dramatic, if not even slightly ironic, when the hard man of facts, Gradgrind is treated to his own medicine by Bitzer, who was brought up on facts and taught to operate according to self-interest.

In Chapter 8 on the 3rd book, “Garnering”, we see an extreme shift in Gradgrind’s behaviour when his son, Tom, is found out for robbing Bounderby’s bank; and is also being prevented to leave the country by a product of Gradgrind’s very own school of thought: Bitzer. Unlikely to his character, Gradgrind’s faith in his own methods failed when his own flesh and blood’s safety and future was at stake. “’Bitzer,’ said Grandgrind, broken down, and miserably submissive to him, ‘have you a heart?’ ‘The circulation, sir’, returned Bitzer, smiling at the oddity of the question, ‘couldn’t be carried on without one. No man, sir, acquainted with the facts established by Harvey relating to the circulation of the blood, can doubt that I have a heart.’ ‘Is it accessible,’ cried Mr Gradgrind, ‘to any compassionate influence?’ (Dickens, 1995 p220)

At this point, we are treated to further characterisation by Dickens, as Gradgrind’s deepest feelings are unveiled, and from the strong hard man of facts we had so far been accustomed to, to the man begging for mercy, Dickens set the tone for an unexpected turn of events in both the storyline and the change of “heart”. Furthermore, Bitzer’s response to Gradgrind is fairly satirical to us – if not darkly comedic – as his response is purely clinical and he answers in exactly the same way he answered Gradgrind at the very beginning of the story when he was asked to describe a horse: “’Girl number twenty unable to define a horse! /… ‘Girl number twenty possessed of no facts, in reference to one of the commonest of animals! Some boy’s definition of a horse. Bitzer, yours.’” (Dickens, 1995 p5) When Dickens creates the situation, Gradgrind’s dictatorial authority is showcased; his near religious bewilderment with facts is supported by Dickens’s comical characterisation, when the chapter is started with “Thomas Gradgrind, sir. A man of realities. A man of facts and calculations. A man who proceeds upon the principle that two and two are four, and nothing over, and who is not to be talked into allowing for anything over. /… with a rule and a pair of scales, and the multiplication table always in his pocket, sir, ready to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to. /…You might hope to get some other nonsensical belief into the head of George Gradgrind, or Augustus… /…but not into the head of Thomas Gradgrind – no, sir!” (Dickens, 1995 p4). While we also find out the speech is usually delivered as an introduction to the public and friends. This unveils the utilitarian nature of Gradgrind and the type of model he sets for the children at his school; but it also points to the strict emotional suppression the latter lives by. The author here seems to have had the story planned, as such depth into the character of Gradgrind sets a strong image in the reader’s mind, and later (as mentioned earlier), the same Gradgrind – a man of facts – imploring the same Bitzer he (back in Chapter 2) who said “Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive…” (Dickens, 1995 p5) to the question Sissy Jupe failed to answer. Gradgrind by his actions made Bitzer look like a hero, the same Bitzer who would coldly choose to jail the former’s son; while humiliating Sissy Jupe, the one who would provide an escape route for Tom.

Dickens in his own style of narrative elicits a change of feeling and opinion towards the characters as the story progresses. The dramatic effect at the end is the unexpected turn of events when Gradgrind chooses the way of “fancy”, a line of thought he rigidly objected against throughout much of his life. We are left to spectate the soft side of a man who is initially portrayed as a strict utilitarian who disregards any kind of emotion, but only acts on the rational and the calculated. The way he reacts to Bitzer when the latter refuses to give in to emotions is near comical but elicits pity from us. We see the constant theme of fact vs fancy reoccurring, but this time with the sides reversed when a man’s own flesh and blood is at the centre of all gloomy proceedings.

The wedding of Louisa to Bounderby is also a union devoid of feelings, but based on rationality and status. Dickens throughout the book points to problems of society but never claims the solution to be at the other end.

Stephen Blackpool, a man who had the choice to freely choose his partner is introduced in Chapter 10 of Book 1. Blackpool is introduced right after the author asserts his opinion about the hard working people of England. Once again, the tone and mood is set by the description of Coketown as an “ugly citadel” as we are placed in the set to feel the hardship Stephen Blackpool goes through as compared to the more affluent characters such as Bounderby and Gradgrind. The description of the “hands”, as the working class people of the times, is saddening with descriptions such as “lower creatures of the seashore, only hands and stomachs” (Dickens, 1995 p 50). This gives the feeling of Blackpool being used by the upper tier of society, and to soften our feelings for the character, Dickens goes on to explain how he looked older than his age, has had a hard life working in the factories and later we find out that he is subjected to the irrational behaviour of his alcoholic wife; a fruitless marriage that deteriorated. The combined misery of Blackpool sets an example of a good man totally mistreated by fate. The fact of not being able to be with Rachael (due to the marital limitations of the times), and dying horribly in the end. It seems like the imagery of the lower parts of town consuming the honest man that was Stephen Blackpool, as Dickens described the town as being “a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage.” (Dickens, 1995 p18) The negative characterisation of the industrialised city is also a clear indicator of one of the main subjects of Dickens’s disapproval.

The styles of characterisation in the building up of dramatic events is present throughout the novel, however Dickens keeps the debate of Fact vs Fancy as the main guiding thought. The characters are all presented as having their own dilemma to deal with no matter what their social rank and status, however, they are all placed meticulously and depicted precisely in Dickens’s style; which at times defies reality and pushes the audience towards the theatrical and/or the surreal; this works in synchronization with the characters actions and reactions, creating a well-balanced and well-paced plot where the themes of human deficiency – in actions mostly – is successfully portrayed along with interesting points such as fact vs fancy which remains unsolved, but leaves the audience in reflection – free to judge and relate to the characters flexibly and subjectively. Furthermore, the death of some of the “less appealing” characters along with some of the warmer ones, leads to a stale but thoughtful ending; with a near infinite number of morals over the “human” experience to ponder upon.

Bibliography

Main Source (Books/Textbooks):

Dickens. C (1995) Hard Times. Wordsworth Editions Limited, Hertfordshire (Click HERE to purchase from Amazon)

Mardi, 22 Avril 2014 | Danny D’Purb | DPURB.com

____________________________________________________

While the aim of the community at dpurb.com has been & will always be to focus on a modern & progressive culture, human progress, scientific research, philosophical advancement & a future in harmony with our natural environment; the tireless efforts in researching & providing our valued audience the latest & finest information in various fields unfortunately takes its toll on our very human admins, who along with the time sacrificed & the pleasure of contributing in advancing our world through sensitive discussions & progressive ideas, have to deal with the stresses that test even the toughest of minds. Your valued support would ensure our work remains at its standards and remind our admins that their efforts are appreciated while also allowing you to take pride in our journey towards an enlightened human civilization. Your support would benefit a cause that focuses on mankind, current & future generations.

Thank you once again for your time.

Please feel free to support us by considering a donation.

Sincerely,

The Team @ dpurb.com

George Orwell’s Animal Farm Animation(1954)

_________________________________

Trump va devenir «Ça» au Carnaval de Nice

Article: https://www.20minutes.fr/nice/2447467-20190209-donald-trump-va-devenir-ca-carnaval-nice

Orwell revient avec Trump.

https://blogs.mediapart.fr/ficanas/blog/300718/orwell-revient-avec-trump

_________________________________

_________________________________

« Aux personnes frustrées et intellectuellement désespérant, qui ne savent toujours pas pourquoi ils se lèvent chaque matin et quel héritage ils ont l’intention de quitter lorsqu’ils meurent:

“Vous devez apprendre l’art de vous taire quand il n’y a rien à dire, surtout devant un être supérieur intellectuellement. Il faut comprendre que les individus ne sont pas et n’ont jamais été égaux en matière de compétences. Pensez à retourner à l’école et quand vous le faites, apprenez l’art de poser les bonnes questions. Parce que la façon dont vous voyez les choses n’est pas la façon dont le monde fonctionne, en d’autres termes, ce que vous voyez n’est pas ce que vous obtenez. » – Danny J. D’Purb

Traduction(EN): “To the frustrated and intellectually hopeless people who still do not know why they wake up every morning and what legacy they intend to leave when they die:

“You have to learn the art of silence when there is nothing to say, especially in front of individuals who are superior intellectually. It must be understood that individuals are not and have never been equal in terms of skills. Go back to school and when you do, learn the art of asking the right questions. Because the way you see things is not the way the world works, in other words, what you see is not what you get.” -Danny J. D’Purb

_________________________________

Philosophy Review: “The World as Will and Idea”, by Arthur Schopenhauer (1818)

Extract:

Schopenhauer, a pessimistic philosopher, focused on the dark side of life and mental evils and cruelty, which he considered inevitable and that we as psychologists, intellectuals and masters of the mind view as mental disorders that have a negative effect on both the character of the affected and the human environment at large exposed to the vile side of human nature.

This negative view of man’s behaviour and role in life was a sharp contrast to the other more euphoric philosophers who marked the spirits of the generation before him, and who embraced a more idealistic and perhaps a slightly exaggerated euphoric side of man’s mind and character. Though Schopenhauer’s work originally gained little attention at the time it was published [perhaps being too avant-garde for the atavistic institutions of his time], he expressed an interpretation of the world that was dragging and opposed the great ideal of who went before him, such as Victor Schelling and Hegel on some very important points but did not deny expressions of art such as the romantic movement in its various forms.

Schopenhauer who never refrained from publicly criticising people and ideas he disliked was very vocal in his complete contempt for these men, and regarded himself as their great opponent in the ring of the leaders delivering the “Real truth” to mankind and civilisation. Schopenhauer’s work in many ways could be viewed as an extension of another famous German philosopher, namely Immanuel Kant, who preceded him by one generation, delivering his major philosophical work, “a critique of pure reason”. Schopenhauer worked out a system in which reality is known inwardly by a kind of feeling where intellect is only an instrument of the will: the biological will to live and where process rather than result is ultimate.

Schopenhauer’s pessimism lies in his very strong rejection of life. In fact, this rejection is so strong that he even had to address the question of suicide as a solution to life. He fortunately also rejected this “solution” to life, this rejection to life reflected influences with roots in Eastern philosophy, particularly Buddhism, and it is one of the most significant aspects of his work that he was the first Western philosopher to integrate Buddhist thought into Western philosophy. His preoccupation with the evil of the world and the tragedy of life was also somewhat reminiscent of ancient Hindu philosophies. His writings helped to stimulate in Germany an interest in Oriental thought and religion, which can also be seen in the work of many later German philosophers.

In “The World as Will and Idea”, Schopenhauer also considered the important question of the function of art. The value of arts to human life in far more depth than any of his predecessors, and even graded each of the arts, such as music, poetry, architecture [etc], from most important to least important. For that reason, his book had not only a profound effect on future philosophers, but also artists, particularly poets and composers, such as the enigmatic Wagner, who felt indebted to him and sent him a letter of gratitude when he was first introduced to Schopenhauer’s work.

Full Article: https://dpurb.com/2018/08/24/essay-philosophy-review-the-world-as-will-and-idea-by-arthur-schopenhauer-1818/