Mis à jour le Mercredi, 14 Avril 2021

Source: An Introduction to Developmental Psychology by Slater & Bremner (Blackwell:Oxford, 2nd Edn, 2011)

It is fundamental to undertstand that as human beings, whatever stage of our lives we are, in order to be able to function fully in our daily lives and in any other activity we first of all need to have a strong foundation. That foundation is our brain, and hence, if our brain [i.e. the hardware] is not physiologically within the limits of what is deemed fit and healthy, every aspect of our mind will be affected and also of our lives. There is no psyche [mind] without a brain, because this biological hardware given to us by nature throughout the course of the shared evolutionary history of primates on planet Earth, allows us to experience every aspect of our lives, both physical and psychical [i.e. mental].

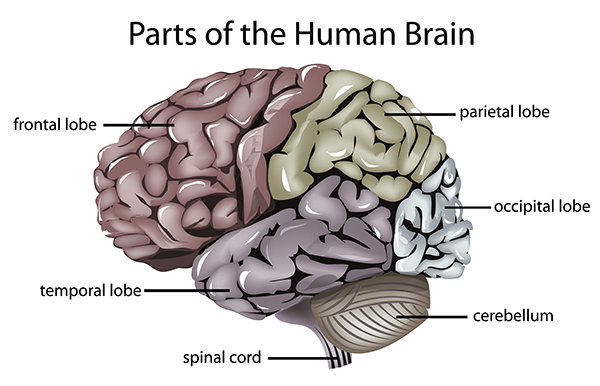

So, before diving deeper into the depth of children’s development, we are going to explore this link between brain and behaviour in order to get a foundation of the importance or a healthy brain, for a healthy development and a healthy and fulfulling life, by starting with how brain damage can affect our personalities and mental abilities; we are going to look at the Frontal lobe, which is the part of the brain behind our forehead responsible for problem solving, strategic planning, use of environmental instructions to shift procedures, and the inhibition of impulsivity.

Frontal Lobes (& Frontal Lobe Damage)

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Grant & Berg, 1948; Heaton, Chelune,Talley, & Curtis, 1993) has long been used in Neuropsychology and is among the most frequently administered neuropsychological instruments (Butler, Retzlaff, & Vanderploeg, 1991).

The test was specifically devised to assess executive functions mediated by the frontal lobes such as problem solving, strategic planning, use of environmental instructions to shift procedures, and the inhibition of impulsivity. Some neuropsychologists however, have questioned whether the test can measure complex cognitive processes believed to be mediated by the Frontal lobes (Bigler, 1988; Costa, 1988).

The WCST test, until this day remains widely used in clinical settings as frontal lobe injuries are common worldwide. Performance on the WCST test is believed to be particular sensitive in reflecting the possibilities of patients having frontal lobe damage (Eling, Derckx, & Maes, 2008). On each Wisconsin card, patterns composed of either one, two, three or four identical symbols are printed. Symbols are either stars, triangle, crosses or circles; and are either red, blue, yellow or green.

At the start of the test, the patient has to deal with four stimulus cards that are different from one another in the colour, form and number of symbols they display. The aim of the participant would be to correctly sort cards from a deck into piles in front of the stimulus cards. However, the participant is not aware whether to sort by form, colour or by number. The participant generally starts guessing and is told after each card has been sorted whether it was correct or incorrect.

Firstly they are generally instructed to sort by colour; however as soon as several correct responses are registered, the sorting rule is changed to either shape or number without any notice, besides the fact that responses based on colour suddenly become incorrect. As the process continues, the sorting principle is changed as the participant learns a new sorting principle.

It has been noted that those with frontal lobe area damage often continue to sort according to only one particular sorting principle for 100 or more trials even after the principle has been deemed as incorrect (Demakis, 2003). The ability to correctly remember new instructions with for effective behaviour is near impossible for those with brain damage: a problem known as ‘perseveration’.

It has been noted that those with frontal lobe area damage often continue to sort according to only one particular sorting principle for 100 or more trials even after the principle has been deemed as incorrect (Demakis, 2003). The ability to correctly remember new instructions with for effective behaviour is near impossible for those with brain damage: a problem known as ‘perseveration’.

Another widely used test is the ‘Stroop Task’ which sets out to test a patient’s ability to respond to colours of the ink of words displayed with alternating instructions. Frontal patients are known for badly performing to new instructions. As the central executive is part of the frontal lobe, other problems such as catatonia – a condition where patients remain motionless and speechless for hours while unable to initiate – can arise. Distractibility has also been observed, where sufferers are easily distracted by external or internal stimuli. Lhermite (1983) also observed the ‘Utilisation Syndrome’ in some patients with Dysexecutive Syndrome (Normal & Shallice, 1986), who would grab and use random objects available to them pathologically.

Incomplete Frontal Lobe Development & Impulsiveness in Children

The Frontal lobe, responsible for most executive functions and attention, has shown to take years [at least 20] to fully develop. The Frontal lobe [located behind the forehead] is responsible for all thoughts and voluntary behaviour such as motor skills, emotions, problem-solving and speech.

In childhood, as the frontal lobe develops, new functions are constantly added; the brain’s activity in childhood is so intense that it uses nearly half of the calories consumed by the child in its development.

As the Pre-Frontal Lobe/Cortex is believed to take a considerable amount of at least 20 years to reach maturity (Diamond, 2002), children’s impulsiveness seem to be linked to neurological factors with the Pre-Frontal Lobe/Cortex; particularly, their [sometimes] inability to inhibit response(s).

The idea was supported by developmental psychologist and philosopher Jean Piaget‘s Theory of Cognitive Development of Children [known for his epistemological studies] where he showed the A-not-B error [also known as the “stage 4 error” or “perseverative error”] is mostly made by infants during the substage 4 of their sensorimotor stage.

Researchers used 2 boxes, marked A and B, where the experimenter had repeatedly hid a visually attractive toy under the Box A within the infant’s reach [for the latter to find]. After the infant had been conditioned to look under Box A, the critical trial had the experimenter move the toy under Box B.

Children of 10 months or younger make the “perseveration error” [looked under Box A although fully seeing experimenter move the toy under Box B]; demonstrating a lack of schema of object permanence [unlike adults with fully developed Frontal lobes].

Frontal lobe development in adults was compared with that in adolescents, e.g. Sowell et al (1999); Giedd et all (1999); who noted differences in Grey matter volume; and differences in White matter connections. Adolescents are likely to have their response inhibition and executive attention performing less intensely than adults’. There has also been a growing & ongoing interest in researching the adolescent brain; where great differences in some areas are being discovered.

The Pre-Frontal Lobe/Cortex [located behind the forehead] is essential for ‘mentalising’ complex social and cognitive tasks. Wang et al (2006) and Blakemore et al (2007) provided more evidence between the difference in Pre-Frontal Lobe activity when ‘mentalising’ between adolescents and adults. Anderson, Damasio et al (1999) also noted that patients with very early damage to their frontal lobes suffered throughout their adult lives.

2 subjects with Frontal Lobe damage were studied:

1) Subject A: Female patient of 20 years old who suffered damages to her Frontal lobe at 15 months old was observed as being disruptive through adult life; also lied, stole, was verbally and physically abusive to others; had no career plans and was unable to remain in employment.

2) Subject B was a male of 23 years of age who had sustained damages to his Frontal lobe at 3 months of age; he turned out to be unmotivated, flat with bursts of anger, slacked in front of the television while comfort eating, and ended up obese in poor hygiene and could not maintain employment. [However…]

Reflections

While research and tests have proven the link between personality traits & mental abilities and frontal brain damage, the physiological defects of the frontal lobe would likely be linked to certain traits deemed negative by a subject willing to be a functional member of society [generally Western societies].

However, personality traits similar to the above Subjects [A & B] may in fact not always be linked to deficiency and/or damage to the frontal lobes; as many other factors are to be considered when assessing the behaviour & personality traits of subjects; where [for example] violence and short temper may [at times] be linked to a range of factors and environmental events during development, or other mental strains such as sustained stress, emotional deficiencies due to abnormal brain neurochemistry, genetics, or other factors that may lead to intense emotional reactivity [such as provocation or certain themes/topics that have high emotional salience to particular subjects, ‘passion‘]

THE 3 MAJOR THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

In 1984, Nicholas Humphrey described us as “nature’s psychologists’” or homo psychologicus. What he meant was that as intelligent social beings, we tend to use our knowledge of our own thoughts and feelings – “introspection” – as a guide for understanding how others are likely to think, feel and hence, behave. He also argued that we are conscious [i.e. we have self-awareness] precisely because such an attribute is useful in the process of understanding others and having a successful social existence – consciousness is a biological adaptation that enables us to perform introspective psychology. Today, we are confident in the knowledge that the process of understanding others’ thoughts, feelings and behaviour is an ability that develops through childhood and most likely throughout our lives; and according to the greatest child psychologist of all time, Jean Piaget, a crucial phase of this process occurs in middle childhood.

Developmental psychology can be characterised as the field that attempts to understand and explain the changes that happen over time in the thought, behaviour, reasoning and functioning of a person due to biological, individual and environmental influences. Developmental psychologists study children’s development, and the development of human behaviour across the organism’s lifetime from a variety of different perspectives. Hence, if we are studying different areas of development, different theoretical perspectives will be fundamental and may influence the ways psychologists and scholars think about and study development.

Through the systematic collection of knowledge and experiments, we can develop a greater understanding and awareness of ourselves than would otherwise be possible.

Focussing on changes with time

The new born infant is a helpless creature, with communications skills that are limited along with few abilities. By 18 – 24 months, the end of the period of infancy – this scenario changes. The child has now formed relationships with others, has gained knowledge about the aspects of the physical world, and is about to undergo a vocabulary explosion as language development leaps ahead. At the time of adolescence, the child has turned into a mature, thinking individual actively striving to come to terms with a fast changing and complex society.

The important contribution to development, is maturation and the changes resulting from experience that intervene between the different ages and stages of childhood: the term maturation refers to those aspects of development that are primarily under genetic control, and which are relatively uninfluenced by the environment. An example would be puberty, and although its onset can be affected by environmental factors such as diet, the changes that occur are genetically determined.

Development Observed

The biologist, Charles Darwin, notable for his theory of evolution, made one of the earliest contributions to our understanding of child psychology in his article “A biographical sketch of an infant” (1877), which was based on observations of his own son’s development. By the early 20th century, most of our understanding of psychological development was not based on scientific methodology as much was still based on anecdotes and opinions of qualitative analysis, a method that strict empiricists have never managed to grasp or like. Nevertheless, knowledge was still being organised through both observation and experiment and during the 1920s and 1930s the study of child development started to grow as a movement, particularly in the USA with the founding of Institutes of Child Study or Child Welfare in university centres such as Iowa and Minnesota. Minute observations were made of young children in their developmental phase along with normal and abnormal behaviour and adjustment. In the 1920s Jean Piaget started his long and passionate career in child psychology, blending observation and experiment in his studies of children’s thinking.

The observations carried out in naturalistic settings was soon criticised by the empiricists of the behavioural movement in the 1940s and 1950s [although it continued to be the method of choice in the study of animal behaviour by zoologists]. This led to many psychologist carrying their experiments under laboratory conditions with statistical methods, and such experiments although come with some advantages from the perspective of empirical statistics, they do have limitations and drawbacks [e.g. on measuring qualitative aspects of personality such as emotions, values, etc]. It should be noted that much of the laboratory work on child development from the 1950s and 1960s has been described by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979) as “the science of the behaviour of children in strange situations with strange adults”.

Schaffer (1996, pp. xiv – xvii) notes other changes in the methods in which psychologists now approach child development, such as the importance in understanding the processes of how children grow and develop rather than simply outcomes, and to integrate findings from a range of sources at different levels of analysis – for example meaningful others, community [geography, socio-linguistics, arts, etc] and culture [religion, nationality(ies), education, class, etc).

In the course of this essay, we will be integrating perspectives to make the most of the findings in distinguishing differences in personality, by reflecting on the links to be made by psychologists between the concept of the child’s “internal working model of relationships” and discoveries about the “theory of mind”.

It is fundamental to acknowledge that psychology itself is mostly based on accurate approximations due to the statistical methods used and the problematic nature of the qualitative variables measured, and not precision. And with this in mind, we should accept the complementary virtues of various different methods of investigation and gain a sense that the child’s process of development and the socio-behavioural context in which they exist are closely intertwined, each having an influence on the other.

Defining development according to world views

Intellectuals and researchers who study development also have different views on the topic, that is, the way in which development is defined, and the areas of development that are of interest to individual researchers generally orients them towards specific methodologies and philosophy when studying development.

We are now going to look at the 2 main views in the study of development given by psychologists who hold different views or sometimes combine elements of both, like ourselves, being firmly on the organic perspective of development and construction.

A world view [also known as paradigm, model, or world hypothesis] can be characterised as “a philosophical system of thinking, perceiving and feeling [ideas and more] that serves to organise a set or family of scientific theories and associated scientific methods” (1986, p. 42).

They are beliefs we adopt because it aligns with our values, and these are qualitative and often not open to common reductive empirical tests – that is precisely why we believe them!

Lerner and others note that many developmental theories appear to fall under one or two world views: organismic and mechanistic.

Organismic World View

The organismic world view which is the main view that we adopted to be the foundation of the Organic Theory, is one that sees a human being on earth as a biological organism that is inherently active and continually interacting with the environment [all aspects and dimensions], and therefore helping to shape its own development. The organismic worldview emphasises the interaction between maturation and experience that leads to the development of new internal, psychological structures for processing environmental input (e.g. Getsdottir & Lerner, 2008).

As Lerner states: “The Organismic model stresses the integrated structural features of the organism. If the parts making up the whole become reorganised as a consequence of the organism’s active construction of its own functioning, the structure of the organism may take on a new meaning; thus qualitatively distinct principles may be involved in human functioning at different points in life. These distinct, or new, levels of organisation are termed stages…” (p.57). A good analogy would be qualitative changes that take place when the molecules of two gasses hydrogen and oxygen, combine to form a liquid, water. Many other qualitative changes happen to water when it changes from frozen (ice) to liquid (water) to steam (vapour). Depending on the temperature, these qualitative changes in the state of water are easily reversed, BUT in human development the qualitative changes that take place are very rarely, if ever, reversible – that is, each new stage represents an advance on the previous stage, and the organism [human being] does not regress to former stages.

The main argument is that the new stage is not simply reducible to components of the previous stage; it represents new characteristics that were not present in the previous stage.

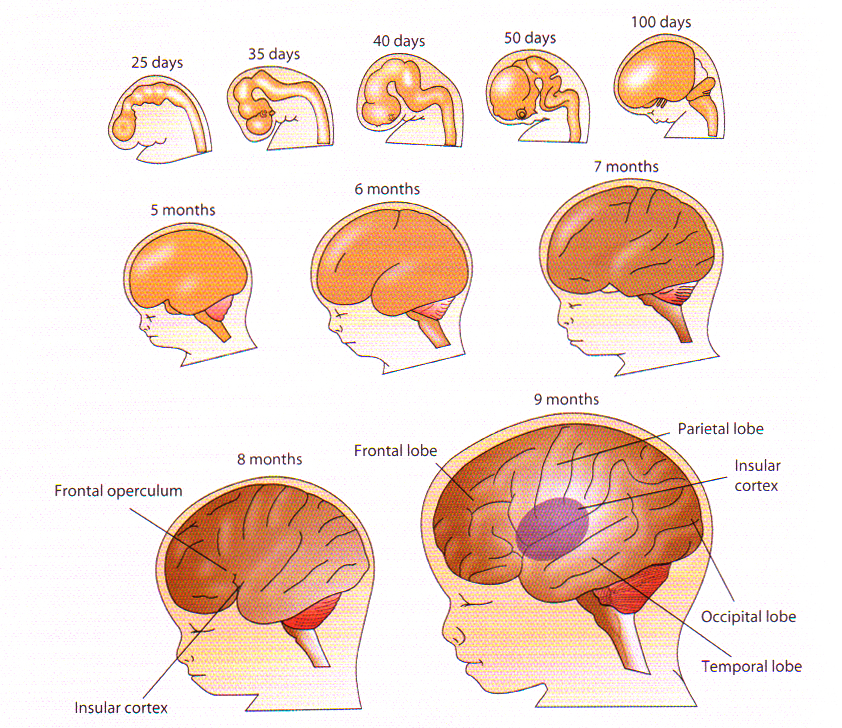

For example, the organism appears to pass through structural changes during foetal development [See Picture A].

PICTURE A. Development of the human foetal brain / Source: Adapted from J.H.Martin (2003), Neuroanatomy Text and Atlas (3rd ed., p.51). Stamford, CT:Appleton & Lange.

In the initial stage [Period of the Ovum – first few weeks after conception] cells multiply and form clusters; in the second stage [Period of the Embryo – 2 – 8 weeks] the major body parts are formed by cell multiplication, specialisation and migration as well as cell death; in the last stage [Period of the Foetus] the body parts mature and begin to operate as an integrated system [e.g. head orientation towards and away from stimulation, arm extensions and grasping, thumb sucking, startles to loud noises, and so on (Fifer, 2010; Hepper, 2007)]. It is important to understand that similar stages of psychological development are postulated to happen after birth also, and the individual from one stage to another is different with new abilities that cannot be reversed.

Jean Piaget is perhaps the greatest and best example of a successful organismic theorist. Piaget suggested that cognitive development occurs in stages and that the reasoning of the child at one stage is qualitatively different from that of the earlier or later stages.

“Chaque civilisation se forge un mythe destiné à expliquer son apparition et construit sa tradition écrite autour d’un support privilégié” / Découvrez (Liens): (i) l’aventure des écritures et (ii) l’aventure du livre | Source: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF)

The main job of the developmental psychologist who believes in the organismic worldview [like ourselves] is to determine when [i.e., at what age?] different psychological stages operate and what variables and processes represent the different between stages and determine the transition between them.

Mechanistic World View

From the mechanistic world view, it is assumed that a person can be broken down into components and can be represented as being like a machine [such as a computer], which is inherently passive until stimulated by the environment [this view seems to be more in line with the early British thinkers about the brain]. Human behaviour is reducible to the operation of fundamental behavioural units [e.g. habits] that are acquired in a progressive, cumulative manner. The mechanistic view assumes that the frequency of behaviours can increase with age due to various learning processes and they can decrease with age when they no longer have any functional consequence, or lead to negative consequences [such as punishment]. The developmental psychologists job here is to study environmental factors, or principles of learning, which determine the way organisms respond to stimulation, and which results in increases, decreases, and changes in behaviour.

Quite unlike the organismic world view, the mechanistic world view sees development as reflected by a more continuous growth function, rather than occurring in qualitatively different stages, and the child is believed to be passive rather than active in shaping its own development and its environment. This mechanistic view is generally embraced by behaviourists and cognitive-behaviourists who function on a reductionist philosophy based on the limitations of the scientific method when faced with understanding psychology and the mechanism of mind; instead they tend to focus on measurable behaviour and treat the brain as an information processing centre with a highly similar logic to a computer. The mechanistic view while being fairly grotesque due to its reductionist values, has revealed to be very practical in the study of human-machine interaction and along with new cognitive methods, it has helped to enhance the design of technological equipment to improve human experience in a wide range of areas.

As for us, we are mostly on the perspective of the organismic school of thought but refuse to completely dismiss all the mechanistic world view’s elements, because some of it can be embedded as secondary cognitive processes carried out by the conscious or preconscious areas of the mind when appraising stimuli from an organism’s environment. Hence, some elements can be embedded in understanding interaction with basic objects and elements of an organism’s “external” [not internal] environment, but to fully base our thoughts and behaviour on a mechanistic world view would arguably be irrationally reductionist.

Theories of Development

“Es gibt nichts Praktischeres al seine gute Theorie.”

–Emmanuel Kant (1724 – 1804)

“There is nothing so practical as a good theory.”

-Kurt Lewin (1944, p. 195)

Human development is complex and it would be irrational to expect a single universal theory of development that could do justice to this complexity, and indeed no theory of development attempts to do so. Each theory attempts to account for only a limited range of development and it is often the case that within each area of development there are competing theoretical views, each attempting to account for the same aspects of development. We shall see below some of this complexity and conflict in our account of different theoretical views.

First of all, it would be helpful to understand what is implied by a “Theory” in the field of developmental psychology. A theory of development is a scheme or system of ideas that is generally based on evidence and attempts to explain, describe and predict behaviour and development. So, from this account, it is quite clear that a theory aims to bring order to what might otherwise be a chaotic mass of information – and hence why there may indeed not be anything more practical than a good theory.

We usually deal with at least 2 kinds of theory in every area of development, we have the minor theories [that are generally concerned with very specific and narrow areas of development such as eye movements, the origins of pointing and so on], and we have the major theories which are the ones we are primarily interested in as they attempt to explain large areas of development.

They have been divided in 3 groups for the purpose of this essay, with cognition, emotion and motivation in focus:

(I) The Theory of Cognitive Development of Jean Piaget

(II) The Theory of Attachment in Emotional Development by John Bowlby

(III) The Genetic/Psychosexual Model of Development by Sigmund Freud

__________

(I) The Theory of Cognitive Development (Jean Piaget)

The theory of cognitive development we are interested in is that of Jean Piaget who saw children as active agents in shaping their own development, and not simply blank slates who passively and unthinkingly responds to whatever the environment throws at them or treats them to [an assumption that is insulting to human intelligence, hence why we do not subscribe blindly to the passive school of thought but only consider some elements related to very basic cognitive processes].

This suggests that children’s behaviour and development is motivated largely intrinsically (internally) rather than extrinsically (externally).

For Piaget and intellectuals with a firm belief in the mind as an active entity, children learn to adapt to their environment and as a result of their cognitive adaptations they are now better able to understand their world. Adaptation is an act that all living organisms have evolved to do and as children adapt, they also gradually construct more advanced understanding [internal working models] of their worlds.

These more advanced understanding of the world reflect themselves in the appearance of new stages of development. Piaget’s theory is the best and most accomplished example of the organismic world view, and it portrays children as inherently active, continually interacting with various dimensions of their environments, in such a way as to shape their own development.

With this assumption in mind, Piaget’s theory is also often referred to the Constructivist Theory.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development (0 – 12 yrs)

Jean Piaget’s theory developed out of his early interest in observing animals in their natural environment. Piaget published his first article at the age of 10 about the description of an albino sparrow that he had observed in the park, and before the age of 18, journals had accepted several of his papers about molluscs. During his adolescent years, the young theorist developed a keen interest in philosophy, particularly “epistemology” [the branch of philosophy focused on knowledge and the acquisition of it]. However, his undergraduate studies were in the field of biology and his doctoral dissertation was once again, on molluscs.

For a short while, Piaget then worked at Bleuler’s psychiatric clinic where his interest in psychoanalysis grew. As a results, he moved to France and attended the Sorbonne university, in 1919 to study clinical psychology and also pursued his interest in philosophy. In Paris, he worked in the Binet Laboratory with Theodore Simon on the standardisation of intelligence tests. Piaget’s task was to monitor children’s correct response to test times, but instead, he became much more interested in the mistakes that children made, and developed the idea that the study of children’s errors could provide an insight into their cognitive processes.

Piaget came to realise that through the process and discipline of psychology, he had an opportunity to create links between epistemology and biology. Through the integration of the disciplines of psychology, biology and epistemology, Piaget aimed to develop a scientific approach to the understanding of knowledge – the nature of knowledge and the ways in which an organism acquires knowledge. As a man who valued richness and detail, Piaget was not at all impressed by the reductionist quantitative methods used by the empiricists of the time, however, he was influenced by the work on developmental psychology by Binet, a French psychologist who had pioneered studies of children’s thinking [his method of observing children in their natural setting was one that Piaget followed himself when he left the Binet laboratory].

Piaget later integrated his own experience of psychiatric work in Bleuler’s clinic with the observational and questioning strategies that he had learned from Binet. Out of this fusion of techniques emerged the “Clinical Interview” [an open-ended, conversational technique for eliciting children’s thinking (cognitive) processes]. It was the child’s own subjective judgement and explanation that was of interest to Piaget, as he was not testing a particular hypothesis, but rather looking for an explanation of how the child comes to understand his or her world. The method is not simple, and the team of Piaget’s researchers had to be trained for 1 year before they actually started collecting data. They were trained and educated about the “art” of asking the right questions and testing the truth of what the children said.

Piaget’s career was devoted to the quest for the mechanisms guiding biological adaptation, and also the analysis of logical thought [that derives from these adaptations and interaction with the exterior environment] (Boden, 1979). He wrote more than 50 books and hundreds of articles, correcting many of his earlier ideas in later life. At its core, the theory of Jean Piaget is concerned with the human need to discover and acquire deeper understanding and knowledge.

Piaget’s incredible output of concepts and ideas characterises his attitude towards constant construction and reconstruction of his theoretical system, which was quite consistent with his philosophy of knowledge, and perhaps indirectly to the school of thought of the mind as an “active” entity.

This section will explore the model of cognitive structure developed by Piaget along with the modifications and some of the re-interpretations that subsequent Piagetian researchers have made to the master’s initial ideas. Although many details have been questioned, it is undeniable that Piaget’s contribution to the understanding of thinking processes [cognitive] of both children and adults.

One great argument made by the theorist suggested that if we are to understand how children think we ought to look at the qualitative development of their problem-solving abilities.

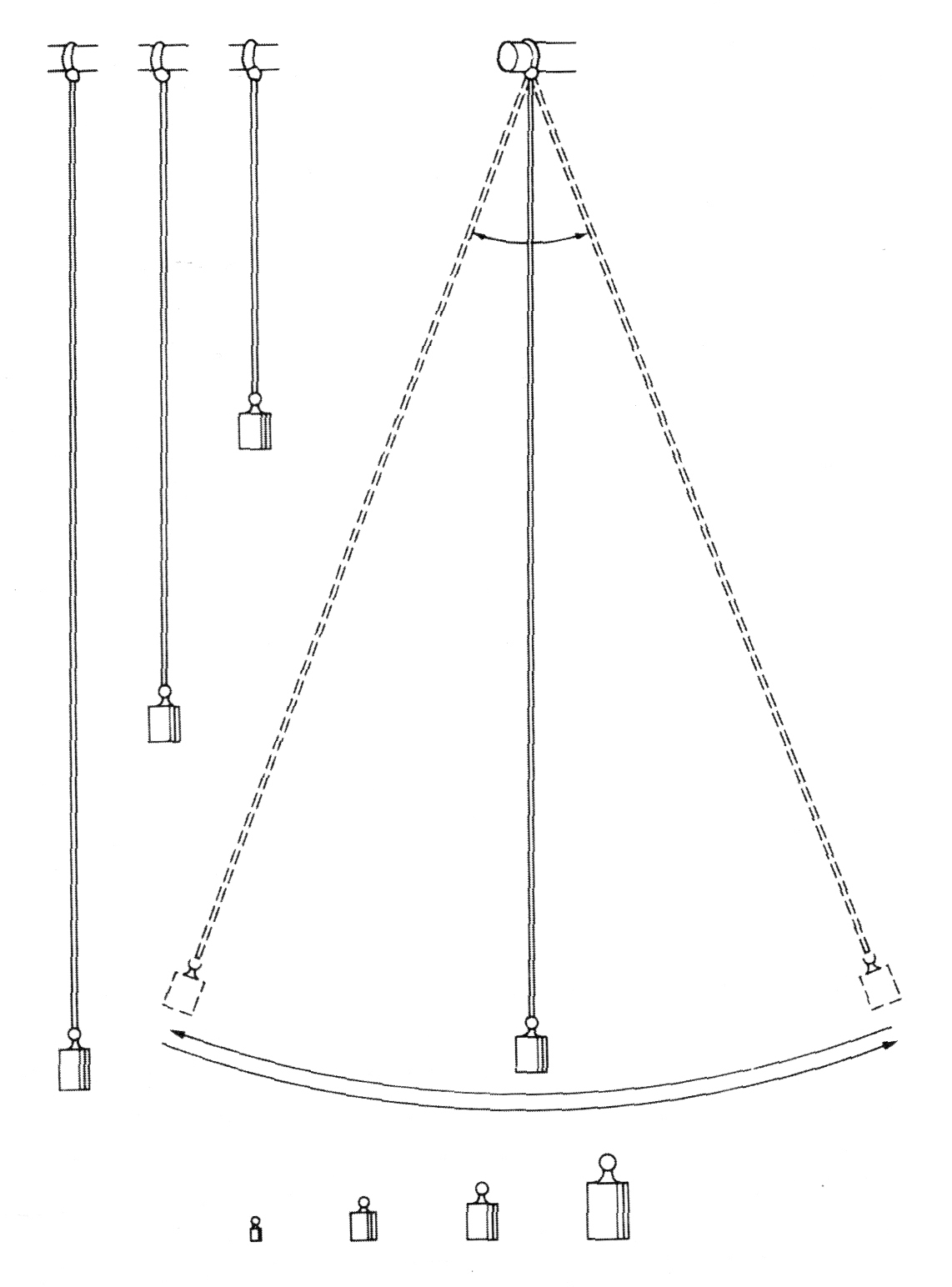

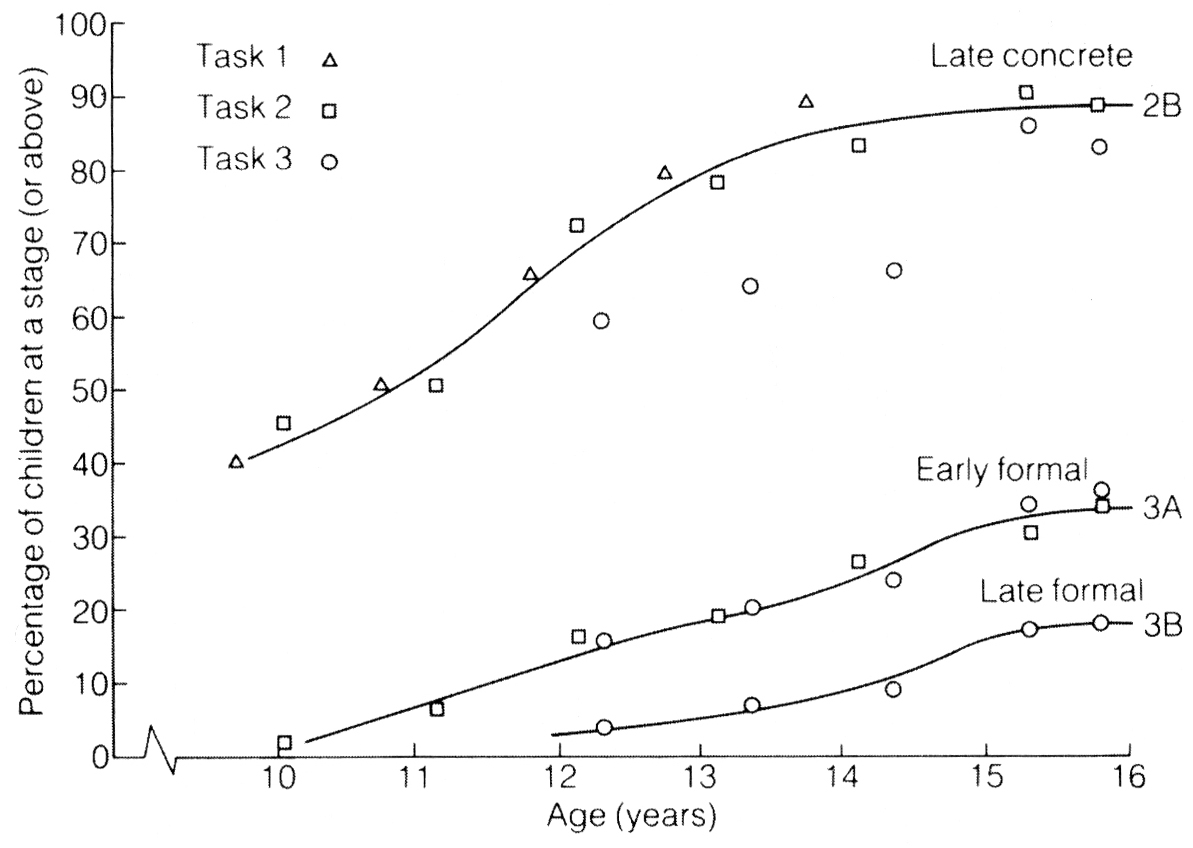

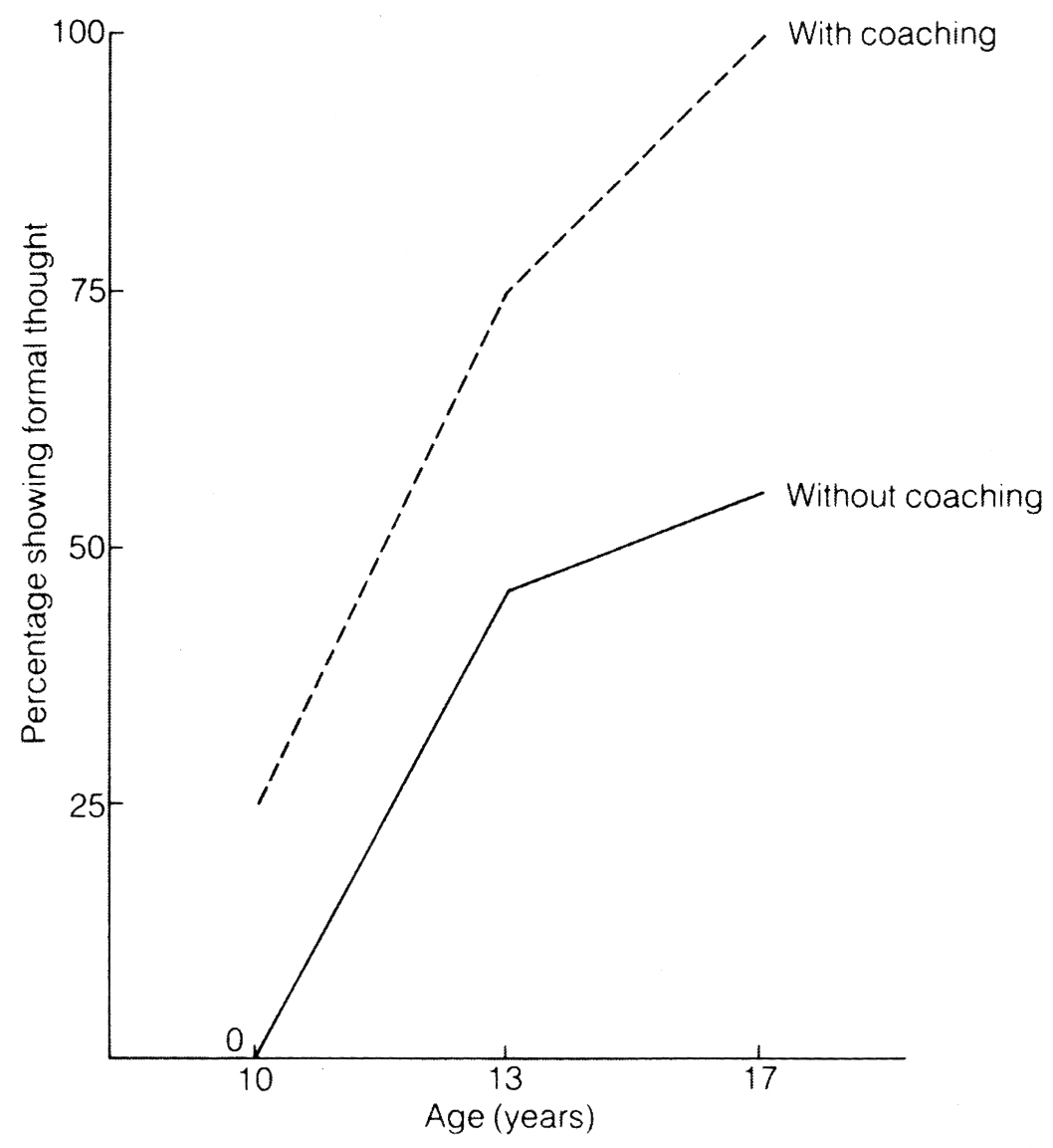

Two famous examples from Piaget’s experiments will be considered that explore the thinking processes in children, showing how they develop more sophisticated problem-solving skills.

Example 1 – One of Piaget’s dialogue with a 7-year-old

Adult: Does the moon move or not?

Child: When we go, it goes.

Adult: What makes it move?

Child: We do.

Adult: How?

Child: When we walk. It goes by itself.

(Piaget, 1929, pp. 146-7)

From this example and other observations based on the similar theme, Piaget described a particular period in childhood which is marked by egocentrism. Since the moon appears to move with the child, she concluded that it does indeed do so. But as the child grows and her sense of logic follows, there is a shift from her own egocentric perspective where the child starts to learn to differentiate between what she sees and she “knows”. Gruber and Vonèche (1977) provide a good example of how an older child used her sense of logic to investigate the movement of the moon. This particular child had sent his younger brother for a walk down the garden while he himself remained immobile. The younger child reported that the moon moved with him, but the older boy realised from his observation that the moon did not move and could then disprove this wrong information with his brother.

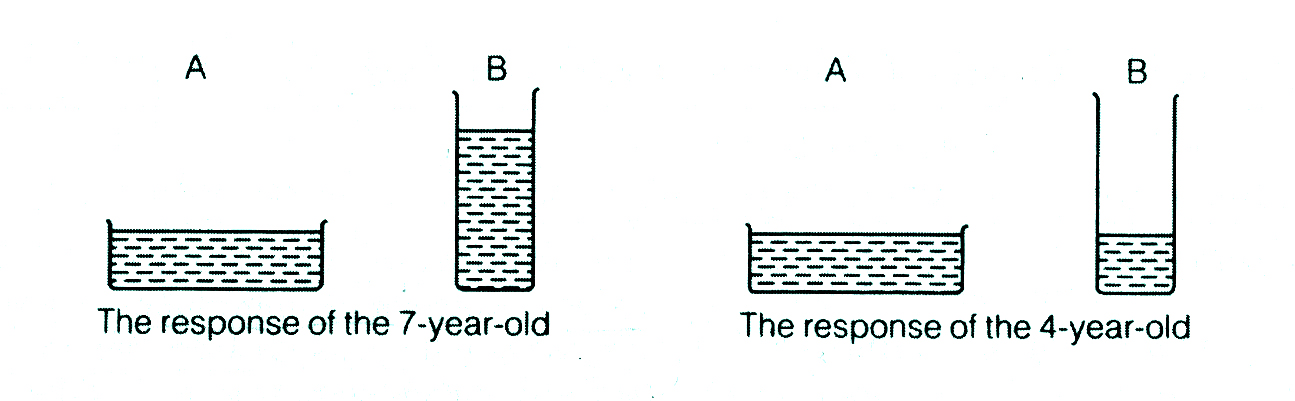

Example 2 – Estimating the Quantity of a Liquid

FIGURE A. Estimating a quantity of liquid

This example is taken from Piaget’s research into children’s understanding of quantity. Let us assume that John [aged 4] and Mary [aged 7] are given a problem; two glasses, A and B, are of equal capacity [volume] but glass A is short and wide and glass B is tall and narrow [See Figure A]. Glass A is filled to a particular height and the children would then be asked, separately, to pour liquid into glass B [tall and narrow] so that it would contain the same amount as glass A. Despite the striking proportional differences of the 2 containers, John could not grasp that the smaller diameter of glass B requires a higher level of liquid. To Mary, John’s response is incredibly senseless and stupid: of course one would have to add more to glass B. Piaget interestingly saw the depth of the argument that was in the responses of those children. John could not “see” that the liquid in A and the liquid in B are not equal, because his thought processes are using a mechanism that is qualitatively different in terms of reasoning and that is not yet developed [perhaps due to physiological/hardware limitations] and lacks the mental operations that would have allowed him to solve the problem. Mary, the 7 year old girl finds it hard to understand 4 year old John’s stupidity and why he could not perceive his error.

Facing this situation, Piaget brilliantly proposed that the essence of knowledge is “activity” – a line of thought and perspective adopted by many psychologists and intellectuals from the German and French school of Lacan quite opposite to the early British thoughts that assumed the mind to be “passive” and mostly shaped by the effects of the outside environment. This argument is not only one that embraces human ingenuity and creativity and acknowledges our instinctual drives to thrive and succeed but also characterises the mind as an entity with high creative power instead of simple junction of neurons conditioned to react to stimuli from its environment almost helplessly as the “passive” school assumed it to be. Hence, to Piaget and ourselves, the essence of knowledge is “activity”, he could be referring to the infant directly manipulating objects and in doing so also learning about their properties. It may also refer to a child pouring liquid from one glass to another to find out which has more in it. Or it may refer to the adolescent forming hypotheses to solve a scientific dilemma. In the examples mentioned, it is important to note that the learning process of the child is taking place through “action”, whether physical (e.g. exploring a ball of clay) or mental (e.g. thinking of various outcomes and reflecting on what they mean). Piaget’s emphasis on activity was important in stimulating the child-centred approach to education, because he firmly believed that for lasting learning to occur, children would not only have to manipulate objects but also manipulate and define ideas. The major educational implications of Piaget will be discussed later in this section.

Assumptions of Piaget’s Theory of Development: Structure & Organisation

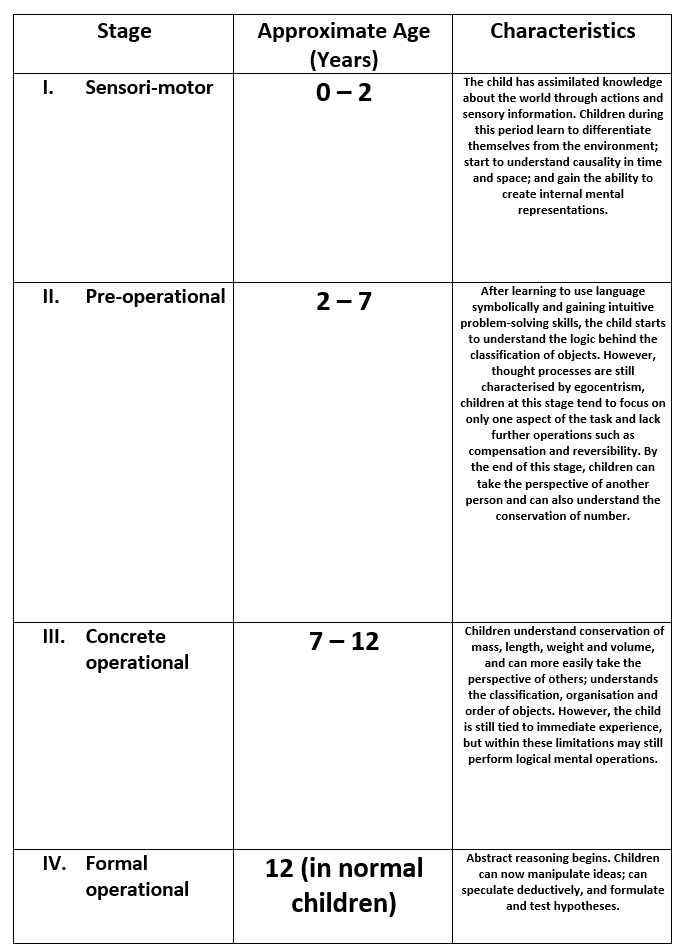

Through his carefully devised techniques, and using observations, dialogues and small-scale experiments, Piaget suggested that children progress through a series of stages in their thinking, each of which synchronises with major changes in the structure or logic of their intelligence. [See Table A]

TABLE A. The Stages of Intellectual Development in Piaget’s Theory

Piaget named the main stages of development and the order in which the occurred as:

I. The Sensori-Motor Stage [0 – 2 years]

II. The Pre-Operational Stage [2 – 7 years]

III. The Concrete Operational Stage [7 – 12 years]

IV. The Formal Operational Stages [12 years but may vary from one child to the other]

Piaget’s structures are sets of mental operations, which can be applied to objects, beliefs, ideas or anything in the child’s world, and these mental operations are known as “schemas”. The schemas are characterised as being evolving structures, in other words, structures that grow and change from one stage to the next.

The details of each section of the 4 stages will be explored below, however it is fundamental that we first understand Piaget’s concept of the unchanging or “invariant” [to use his own term – this may be related to temperament but here it involves another set of abilities] aspects of thought, which refers to the broad characteristics of intelligent activity that remains constant throughout the human organism’s life.

These are the organisation of schemas and their adaptation through assimilation and accommodation.

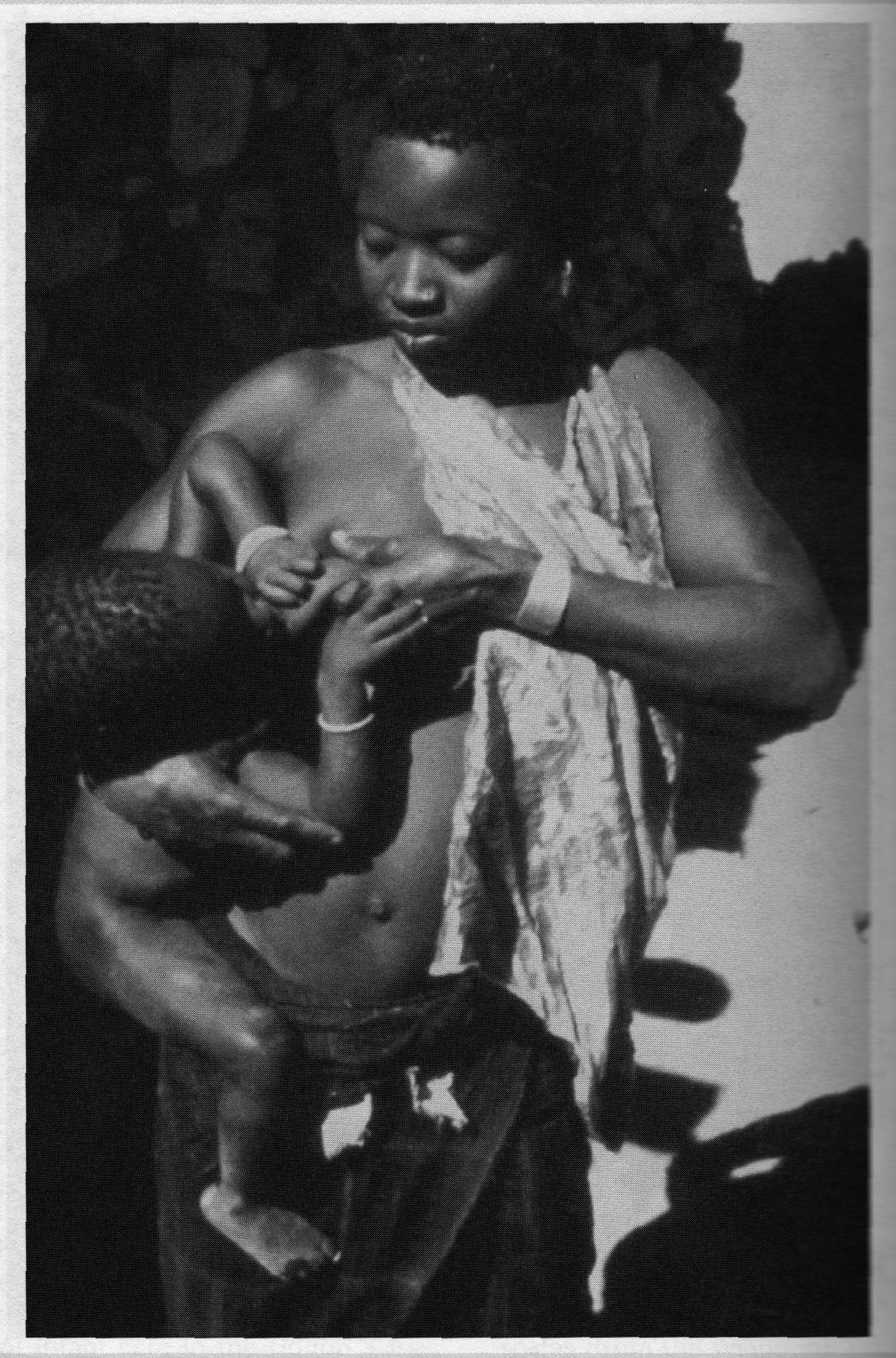

Organisation: Piaget used this term to explain the innate ability to coordinate existing cognitive structures, or schemas, and combine them into more complex systems [e.g. a baby of 3 months old has gained the ability to combine looking and grasping, with the earlier reflex of sucking]. The baby is able to perform all three actions together when feeding from her mother’s breast or a feeding bottle, an ability that the new born child did not originally have in his/her repertoire. A further example would be Ben who at the age of 2 had learned to climb downstairs while carrying objects without dropping them, and also to open doors. This means that he could then combine all three operations to deliver newspaper to his grandmother in the basement flat. To note, each separate operation combines into a new action more complex than the sum of the parts.

The complexity of the organisation also grows as the schemas become more elaborate. Piaget described the development of a particular action schema in his son Laurent as he attempted to strike a hanging object. Initially, Laurent only made random movement towards the object, but at the age of 6 months the movements had evolved and were now deliberate, focused and well directed. As Piaget put it in his description, at 6 months old, Laurent possessed the mental structure that guided the action involved in hitting a toy. Laurent had also gained the ability to accommodate his actions to the weight, size and shape of the toy and its distance from him.

The next invariant function, “adaptation” is characterised by the striving of the organism for balance [or equilibrium] with the environment, and is achieved through the further processes of “assimilation” and “accommodation”. During the process of assimilation, the child’s repertoire of knowledge expands and he/she takes in [learns about] a new experience [and the knowledge acquired with it] and fits it into an existing schema. For example, a child may learn the words “dog” and “car”, and following this enigmatic event, the child may call all animals “dogs” [i.e. different animals taken into a schema related to the child’s understanding of dog], or all vehicles with four wheels are called “cars”. The process of accommodation balances this erroneous process, where the child adjusts an existing schema to fit in with the nature of the environment [i.e. from experience, the child begins to perceive that cats can be distinguished from dogs, and may develop schemas for these 2 different animals – also that cars can be distinguished from other vehicles such as trucks or lorries.

By these two processes, namely assimilation and accommodation, the child achieves a new state of equilibrium which is however not permanent as this balance is generally soon upset as the child assimilates further new experiences or accommodates her existing schemas to another new idea.

Equilibrium only seems to prepare the child for more disequilibrium through further learning and adaptation; these two processes occur together and cannot be thought of separately. Assimilation provides the child with consolidation for mental structures; and accommodation results in growth and change. All adaptations contains the components of both processes and striving for balance between assimilation and accommodation [Remember: Organisation Adaptation + (Assimilation & Accommodation)] leads to the child’s intrinsic motivation to learn [This is also reminiscent of the psychodynamic school of thought as several processes colliding to find balance in its model of the mental life of the individual mind]. When new experiences are within the child’s response range in terms of abilities, then conditions are said to be at their best for change and growth to occur.

The Stages of Cognitive Development

To adepts of Piaget’s outlook, intellectual development is a continuous process of assimilation and accommodation. We will not describe the four stages identified in the development of cognition from birth to about 12 years old [in normal children]. This order is similar for all children but the age these milestones are achieved may vary from one child to another – with the stages being:

I. The Sensori-Motor Stage [0 – 2 years]

II. The Pre-Operational Stage [2 – 7 years]

III. The Concrete Operational Stage [7 – 12 years]

IV. The Formal Operational Stages [12 years but may vary from one child to the other]

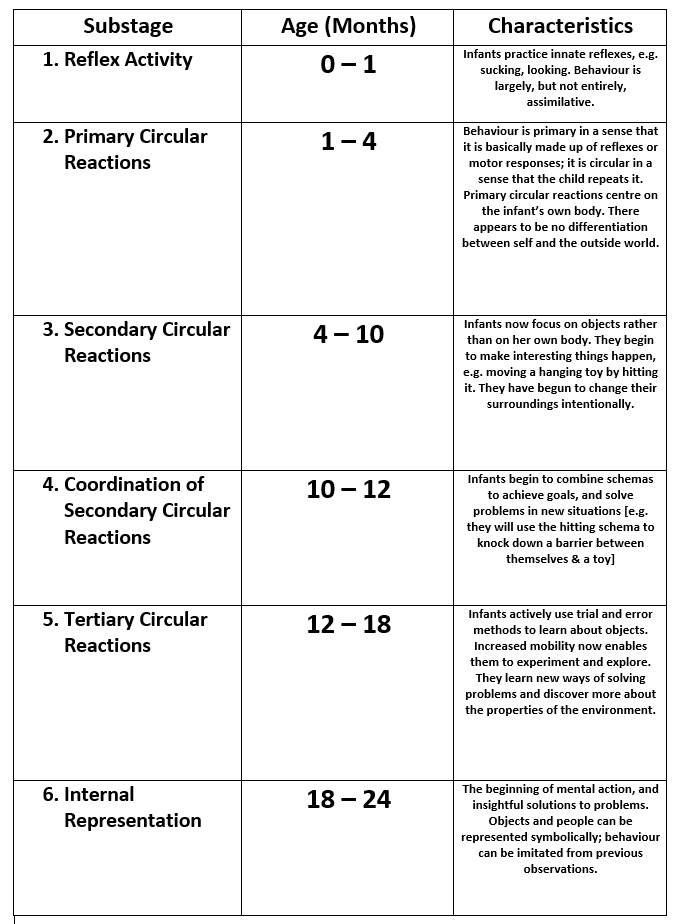

I. The Sensori-Motor Stage (about 0 – 2 years) | Stage 1 of 4

During the sensori-motor stage the child changes from a newborn, who focuses almost entirely on immediate sensory and motor experiences, to a toddler who possesses a rudimentary capacity for thinking. Piaget described in detail the process by which this occurs, by documenting his own children’s behaviour. On the basis of such observations, carried over the first 2 years of life, Piaget divided the sensori-motor stage into 6 sub-stages. [See Table B]

TABLE B. Substages of the sensori-motor period according to Piaget

The first substage, reflex activity, included the reflexive behaviours and spontaneous rhythmic activity with which the infant is born. Piaget called the second substage primary circular reactions. He used the term “circular” to emphasise how children tend to repeat an activity, especially those that are pleasing or satisfying (e.g. thumb sucking). The term “primary” refers to simple behaviours that are derived from the reflexes of the first period [e.g. thumb sucking develops as the thumb is assimilated into a schema based on the innate suckling reflex].

Secondary circular reactions refer to the child’s willingness to repeat actions, but the word “secondary” is used here to point out the behaviours that are the child’s very own. In other words, she is not limited to just repeating actions based on early reflexes, but having initiated new actions, she can now repeat these if they are satisfying. However, at the same time, these actions tend to be directed outside the child (unlike simple actions like thumb sucking) and are aimed at influencing the environment around her.

This is Piaget’s description of his own daughter Jacqueline at 5 months old, kicking her legs (in itself a primary circular reaction) in what gradually ascends to a secondary circular reaction as the leg movement is repeated not just for itself, but is initiated in the presence of a doll.

Jacqueline looks at a doll attached to a string which is stretched from the hood to the handle of the cradle. The doll is approximately the same level as the child’s feet. Jacqueline moves her feet and finally strikes the doll, whose movement she immediately notices… The activity of the feet grows increasingly regular whereas Jacqueline’s eyes are fixed on the doll. Moreover, when I remove the doll Jacqueline occupies herself quite differently; when I replace it, after a moment, she immediately starts to move her legs again.

(Piaget, 1936, p. 182)

In displaying such behaviours, Jacqueline seemed to have established a general relation between her movement and the doll’s, and was also engaged in a secondary circular reaction.

Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions, being substage 4 of the Sensori-motor period, and as the word “coordination” implies, it is particularly at this substage that children begin to combine different behavioural schema. In the following extracted section, Piaget described how his daughter (aged 8 months) combined several schemas, such as “sucking an object” and “grasping an object” in a series of coordinated actions when playing with a new object:

Jacqueline grasps an unfamiliar cigarette case which I present to her. At first she examines it very attentively, turns it over, then holds it in both hands while making the sound apff (a kind of hiss which she usually makes in the presence of people). After than she rubs it against the wicker of her cradle then draws herself up while looking at it, then swings it above her and finally puts it in her mouth.

(Piaget, 1936, p. 284)

Jacqueline’s behaviour illustrates how a new object is assimilated to various existing schema in the fourth substage. In the following stage, that of tertiary circular reactions children’s behaviours become more flexible and when they repeat actions they may do so with variations, which can lead to new results. By repeating actions with variations, children are, in effect, accommodating established schema to new contexts and needs.

The final sub-stage of the sensori-motor period is known as the substage of Internal Representations and it refers to the child’s achievement of mental representation. The previous substages the child has interacted with the world through her physical motor schema, another way of phrasing it would be that, she has acted directly on the world. In this final substage, she can now act “indirectly” on the world because she has developed the capacity to hold mental representations of the world – that is, she can now think and plan.

As evidence for children attaining the level of mental representation, Piaget pointed out that by this substage children have a full concept of object permanence. Piaget noticed that very young infants ignored even highly attractive objects once they were out of sight [e.g. a child reaching for a toy, but then the toy is suddenly covered with a cloth and it immediately leads to the child losing all interest in it and would not attempt to search for it, and might even just look away]. According to Piaget it was only after the later substages that children demonstrated an awareness [by searching and trying to retrieve the object] that the object was “permanently” present even if it was temporarily out of sight. Searching for an object that cannot be seen directly implies that the child has a memory of the object, i.e. a mental representation of it.

It is only towards the end of the sensori-motor period that children demonstrated novel patterns of behaviour in response to a problem. For example, if a child wants to reach for a toy and comes across an object between herself and the desired toy, younger children might just try and reach for the toy directly and it is possible that the child knocks over the object while reaching for the target toy – this is best described as “Trial and Error” performance. In the later substages, the child might solve the problem by instead first removing the object out of the way before reaching for the desired toy. Such structured behaviour suggests that the child was able to plan ahead, which indicates that he/she had a mental representation of what she was going to do.

An example of planned behaviour by Jacqueline was given where she was trying to solve the problem of opening a door while carrying two blades of grass at the same time:

She stretches out her right hand towards the knob but sees that she is cannot turn it without letting go of the grass. She puts the grass on the floor, opens the door, picks up the grass again and enters. But when she wants to leave the room things become complicated. She put the grass on the floor and grasps the door knob but then she realises that in pulling the door towards her she will simultaneously chase away the grass which she placed between the door and the threshold. She therefore picks it up in order to put it outside of the door’s zone of movement.

(Piaget, 1936, pp. 376-7)

Jacqueline solved the problem of the grass and the door before she opened the door. It is assumed that she would have had a mental representation of the problem, which permitted her to work out the solution, before she acted.

A third line of evidence for mental representations comes from Piaget’s observation of deferred imitation, that is when children carry out a behaviour that is a reflection of copied behaviour that was previously taken in by the developing child. Piaget provides a good example of this:

At 16 months old Jacqueline had a visit from a little boy of 18 months who she used to see from time to time, and who, in the course of the afternoon got into a terrible temper. He screamed and he tried to get out of a playpen and pushed it backward, stamping his feet. Jacqueline stood observing him in amazement, having never witnessed such a scene before. The following day, she herself screamed in her playpen and tried to move it, stamping her foot lightly several times in succession.

(Piaget, 1951, p. 63)

This suggests that if the little boy’s behaviour was repeated by Jacqueline a day later, she would have had to have retained an image of his behaviour, i.e. she had a mental representation of what she had seen from the day before, and that representation provided the basis for her own copy of the temper tantrum.

To conclude, during the sensori-motor period, the child advances from very simple and limited reflex behaviours at birth, to complex behaviours at the end of the period. The more complex behaviours depend on the progressive combination and elaboration of the schema, but are, at the beginning, limited to direct interactions with the world – thus, the name Piaget gave to this period because he thought of the child developing through her sensori-motor interaction with the environment. It is only towards the end of that period that the child is not limited to immediate interaction anymore because she has now developed the ability to mentally represent her world [mental representation], and with this ability the child can manipulate her mental images (or symbols) of her world, in other words, she can now act on her thoughts about the world as well as on the world itself.

Revisions of the Sensori-motor Stage

Jean Piaget’s observations of babies during this first stage lasting until 2 years of age, have been largely confirmed by subsequent reseachers, however Piaget may have underestimated children’s mental capacity to organize the sensory and motor information they take in. Several investigators have shown that children have abilities and concepts earlier than Piaget thought.

Bower (1982) examined Piaget’s hypothesis that young children did not have an appreciation of objects if they were not in sight. For this experiment, children a few months old were recruited and shown an object, and shortly after a screen was moved across in front of the object [so that it would be hidden/unseen from the child’s visual field], to then finally be moved back to its original position. This scenario was presented with 2 slight changes: in Condition 1 the object was still in place and hence seen again by the child when the screen was moved back to its original location; and in Condition 2, the object was removed so the child would perceive the object to have disappeared when the screen was moved back. After monitoring the children’s heart rate to measure changes [which reflect surprise]. To go back to Piaget’s assumptions from his qualitative observations, it would be assumed that children of a few months old do not retain information about objects that are no longer present, and if this was the case, we would not register any heart rate change because as there should be no element of surprise [i.e. the child would not expect an object to be there once the screen was moved back to its original location], thus in Condition 2, no reaction should be displayed by the children, however it was found that children displayed more surprise in Condition 2 and Bower inferred that the children would have had an expectation of the object to still be in its position or “re-appear” after the screen was moved back – this would be the evidence that young children must retain a mental representation of the object in their mind [could be interpreted as young children having some basic form of object permanence even if not properly developed at an earlier age than the assumptions of Piaget based on the results of his experimental methods].

In a further experiment, Baillargeon and DeVos (1991) showed 3-month-old children objects that moved behind a screen and then re-appeared from the other side of the screen. The upper half of the screen had a window and in one condition the children saw a short object move behind the screen [the object was small and below the level of the window and hence when it passed behind the screen it was completely out of sight / not visible, until it appeared at the other side of the screen].

In a second condition a taller object was passed behind the screen, and it was high enough to be seen through the window as it passed from one side to the other. Furthermore, Baillargeon and DeVos created an “impossible event” by passing the tall object through the screen without it appearing through the window, and it lead to the children displaying more interest by looking longer at the scenario than that with the small object. This lead to the argument that children reacted so, due to their expectation of the taller object to appear through the window, and hence this would suggest that young children early in the sensori-motor stage have an awareness of the continued existence of objects even when they are out of view. These results along with that of Bower (1982) seem to suggest that young children to have “some” understanding of object permanence earlier than assumed.

Another one of Piaget’s conclusion was also investigated further by another group of researchers who wanted to find out if children only developed planned action [which demonstrated their ability to form mental representations] at the end of the sensori-motor stage. Willatts (1989) placed an attractive toy on a cloth, out of the reach of 9-month-old children; the children could pull the cloth to access the attractive toy. However, the children could not reach the cloth directly since it was not accessible as Willatts placed a light barrier between the child and the cloth [the child had to move the barrier to reach the cloth]. The experiment showed that children were able to access the toy by carrying out appropriate the series of actions [i.e. first moving the barrier, then pulling the cloth to bring the toy within reach]. Most importantly, many of the children carried out the correct actions within the first occasion of being presented with the problem without the need of going through a “trial and error” phase. Willatts argued that for such young children to demonstrate novel planned actions, it may be inferred from such behaviour that they are operating on a mental representation of the world which they can make use of to organise their behaviour before carrying it out [This is also earlier than assumed by Piaget’s experiments].

Another point made by Piaget was that deferred imitation was an evidence that children should have a memory representation of what they had seen earlier. Soon after birth however it was found that babies are able to imitate the facial expression of an adult or the head movement (Meltzoff and Moore, 1983, 1989), however such imitation is performed in the presence of the stimulus being imitated. From Piaget’s experiments, it was initially deduced that stored representations are only achieved by children towards the end of the sensori-motor stage, however, Meltzoff and Moore (1994) showed that 6-week old infants could imitate a behaviour a day after they had seen the original behaviour. In Meltzoff and Moore’s study some children saw an adult make a facial gesture [e.g. sticking out her tongue] and others just saw the adult’s face while she maintained a neutral expression. The next day, all the children in the experiment saw the same adult, however this time, she kept a passive face. Compared to the children who had not seen any gesture, the children who had seen the tongue protrusion gesture the day before were more likely to make tongue protrusions to the adult the second time they saw her. Meltzoff and Moore argued that for the children to be able to perform those actions they would have had to have a mental representation of the action at a much earlier age than Piaget’s experiments concluded

II. The Pre-operational Stage (about 2 – 7 years) | Stage 2 of 4

This stage will be divided in 2 periods: (a) The Pre-conceptual Period (2 – 4 years) and (b) the Intuitive Period (4 – 7 years)

(a) The Pre-Conceptual Period (2 – 4 years)

The pre-conceptual period builds on the ability for internal, or symbolic thought to develop based on the latest advancements during the final stages of the sensori-motor period. During the pre-conceptual period [2 – 4 years old], we can observe a rapid increase in children’s language which, in Piaget’s view, results from the development of symbolic thought. Piaget unlike other theorists of language [who suggested that thought emerges from linguistic competence] argued that thought arises out of action and this idea is supported by research into cognitive abilities of deaf children who, despite limitations in language, have the abilities for reasoning and problem solving. Piaget argued that thought shapes language far more than language shapes thought [at least during the pre-conceptual period], and symbolic thought is also expressed in imaginative play.

However there are some limitations in the child’s abilities at the pre-conceptual period (2-4 years) of the pre-operational stage. The pre-operational child is still centred in her own perspective and finds it difficult to understand that other people can look at things differently. Piaget called this the “self-centred” view of the world and used the term egocentrism.

Egocentric thinking occurs due to the child’s belief that the universe is centred on herself, and thus finds it hard to “decentre”, that is, to take the perspective of another individual. The dialogue below gives an example of a 3-year-old’s difficulty in taking the perspective of another person:

Adult: Have you any brothers or sisters?

John: Yes, a brother.

Adult: What is his name?

John: Sammy.

Adult: Does Sammy have a brother?

John: No.

It is quite clear here that 3-year old John’s inability to decentre makes it hard for the child to realise that from Sammy’s perspective, he himself is a brother.

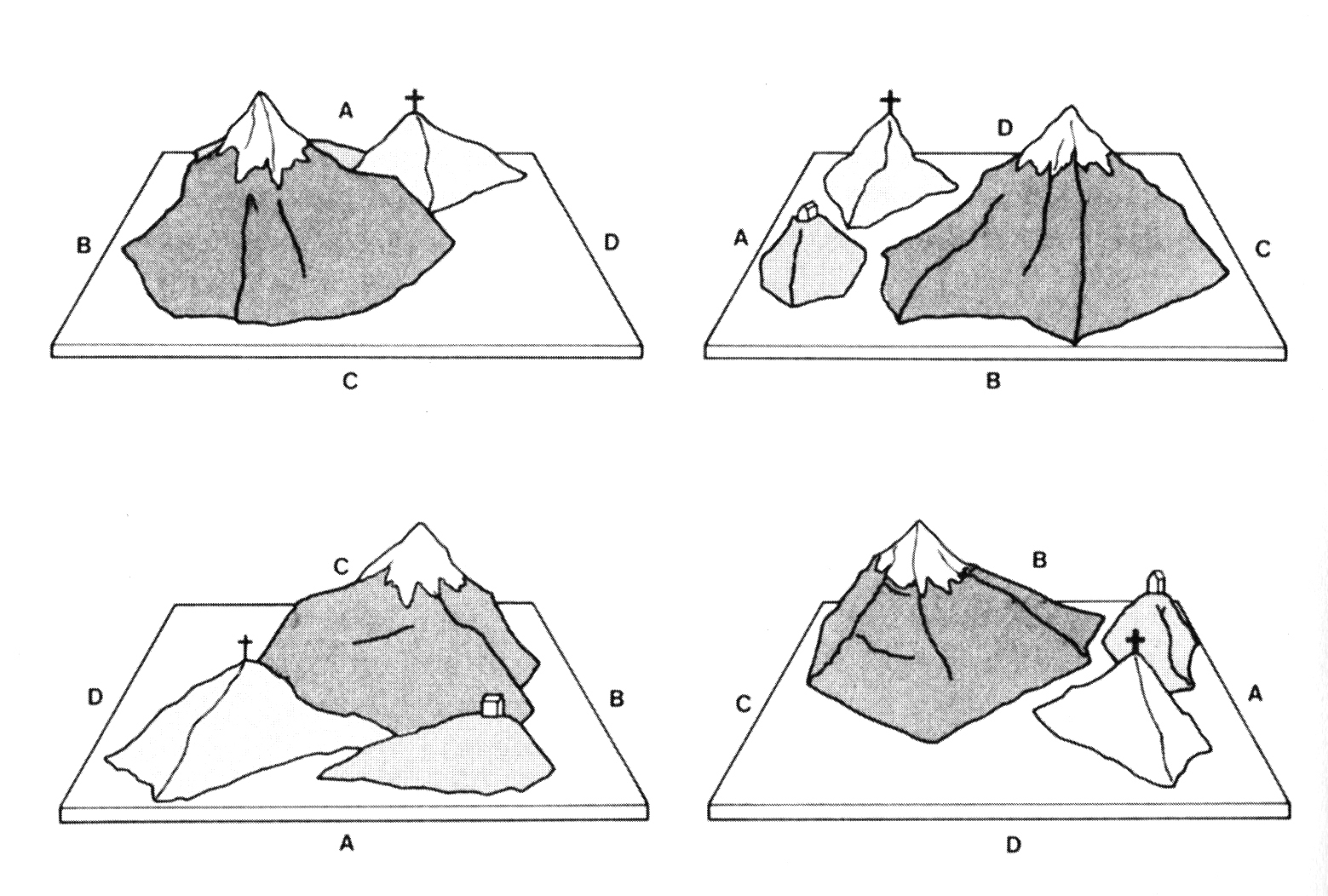

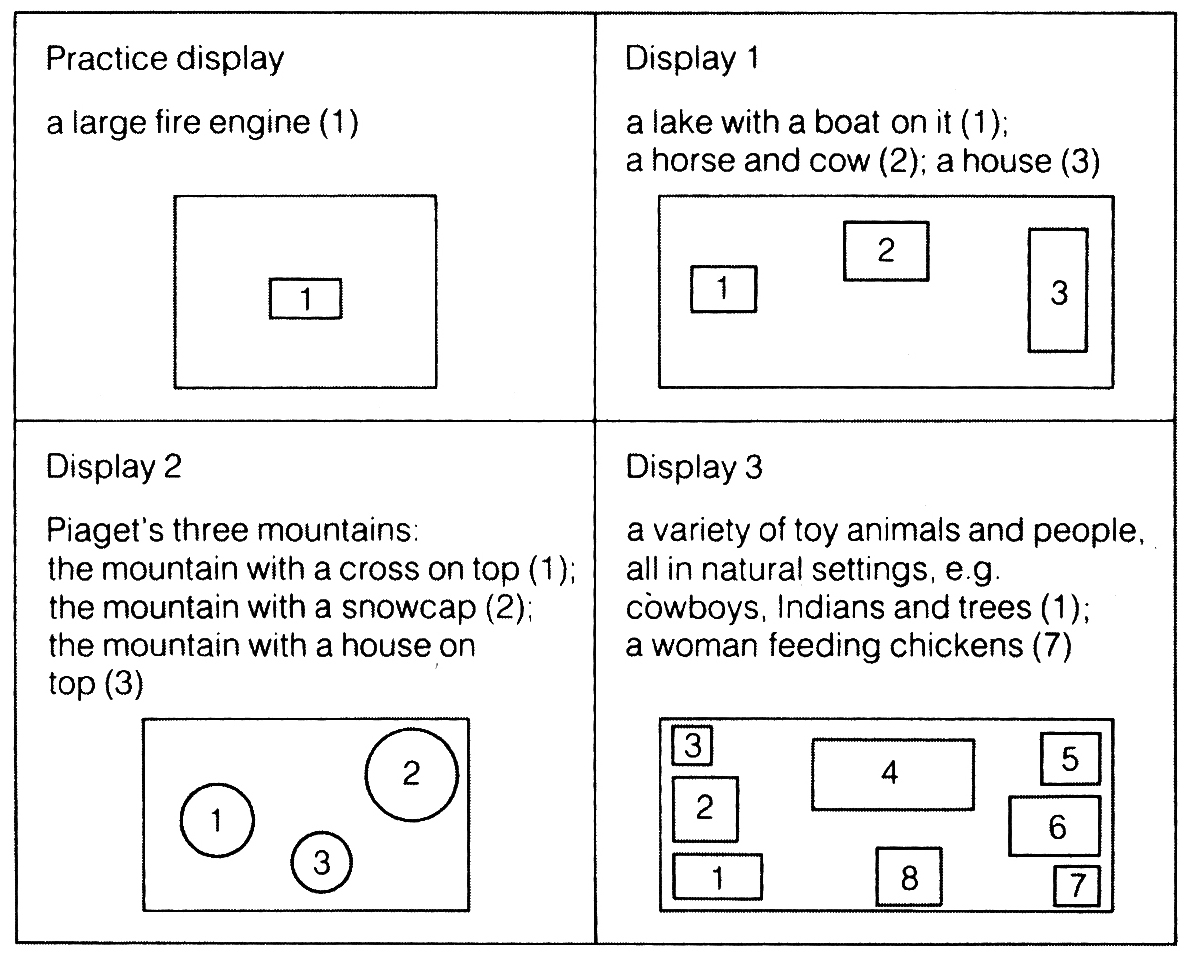

The egocentric trait at this particular period of development is apparent in their flawed perspective taking tasks. One of the most famous experiments carried out by Piaget is the three mountains experiment tasks, and it involves exploring children’s ability to see things from the perspective of another. In 1956, Piaget and Inhelder asked children between the ages of four and twelve [4 – 12 years old] to say how a doll would perceive an array of three mountains from different perspectives [i.e. by placing the doll at different locations].

FIGURE J. Model of the mountain range used by Piaget and Inhelder viewed from 4 different sides

For example in Figure J, a child might be asked to sit at position A, and a doll would be placed at one of the other positions (B, C or D), then the child would be made to choose from a set of different views of the model, the view that the doll could see. When four and five year old children [4 and 5 years old] were asked to do this task, they often chose the view that they themselves could see (rather than the doll’s view) and it was not until 8 or 9 years of age that children could confidently work out the doll’s view. Piaget argued that this should be convincing in asserting that young children were still learning to manage their egocentricity and could not decentre from their own perspective to work out the perspective / view of the doll.

However, several criticisms have been made regarding the 3 mountain tasks, and one researcher, Donaldson (1978) pointed out that the tasks were unusual to use with young children who might not have a good familiarity with model mountains or be used to working out other people’s views of landscapes. Borke (1975) carried out a similar task to Piaget, but instead of using model mountains, he used the layout of toys that young children typically spend time with in play. She also altered the way that children were asked to respond to the question about what a different person’s view would be, and found that children as young as 3 or 4 years of age had some basic understanding of how another person’s perspective would be different from another position. This was much earlier than previously deduced from Piaget’s experiments, and shows that the type of objects and procedures used in a task can have a huge impact on the performance of the children. By using mountains, Piaget may have selected a far too complex content for such young children’s perspective-taking abilities to be demonstrated optimally.

Borke’s Experiment: Piaget’s Mountains Revised & Changes in the Egocentric Landscape

Borke’s main inquisition was about the appropriateness of Piaget’s three mountain tasks for such young children, and was concerned with the aspects of the task that were not related to perspective-taking and whether this might have adversely affected the children’s performance. These aspects were:

(i) the mountain from a different angle or not may not have sparked any interest or motivation in the children

(ii) the pictures of the doll’s views that Piaget had asked the children to select may have been too taxing for their intelligence

(iii) due to the task being unusual in nature, children may have performed poorly because they were unfamiliar with such a task

Borke considered if some initial practice and familiarity with the task would improve the children’s performance, and with those points in mind, Borke repeated the basic design of Piaget and Inhelder’s experiment but changed the content of the task, avoided the use of pictures and gave children some initial practice. She also used 4 three-dimensional displays: there were a practice display and three experimental displays [see FIGURE B].

FIGURE B. A schematic view of Borke’s four three-dimensional displays viewed from above.

Borke’s participants were 8 three-year-old children and 14 four-year-old children attending a day nursery. Grover, a character from the popular children’s television show, “Sesame Street” was used for the experiment as a substitute for Piaget’s doll. There we 2 identical versions of each display (A and B), and Display A was for Grover and the child to look at, and Display B was on a turntable next to the child.

The children were tested individually and were first shown a practice display which consisted of a large toy fire engine. Borke placed Grover at one of the sides of the practice Display A so that Grover could view the fire engine from a point of view [perspective] that was different from the child’s own view of this display.

A duplicate of the fire engine [practice Display B] appeared on a revolving turntable, and Borke briefed the children, explaining that the table could be turned so that the child could look at the fire engine from ANY side. Children were then prompted to turn the table until their view of the Display B matched the exact perspective that Grover had while looking at Display A. If necessary, Borke even helped the children to move the turntable to the correct position or walked the children round Display A to show them the exact view [perspective] that Grover had in view

Once the practice session was over, the child was ready to take part in the experiment itself. This time, the procedures were similar, except no help was provided by the experimenter. Every single child was shown three dimensional displays, one at a time [see FIGURE B].

Display 1 included a toy house, lake and animals

Display 2 was based in Piaget’s model of three mountains

Display 3 included several scenes with figures and animals

Note: There were 2 identical copies of each display, and of course, children had to rotate the second copy which was on a turntable to match the perspective [view] that Grover had in sight [as prepared in the practice session].

What Borke found was that most of the children in the experiment were able to work out Grover’s perspective for Display 1 [three and four-year-olds were correct in 80% of trials] and for Display 3 [three-year-olds were correct in 79% of trials and four-year-olds, in 93% of trials. However, for Display 2 [Piaget’s mountains], the three-year-olds were correct in only 42% of trials and four-year-olds in 67% of trials. Borke calculated an analysis of variance, and found that the difference between Displays 1 & 3 and Display 2 was significant at p < 0.001. As for errors, there were no significant differences in the children’s responses for any of the 3 positions – 31% of errors were egocentric [i.e. child rotated Display B to show their OWN view/perspective of Display A, rather than Grover’s view].

Borke successfully demonstrated that the task had a major influence on the perspective-taking performances of young children. When the display included toys that the children were familiar with and hence recognisable, and when the response involved rotating a turntable to work out Grover’s perspective, even the comparatively complex Display 3 task was successfully achieved by the children.

This seems to suggest that the poor performance by the children in Piaget’s original experiment involving three mountains was due in part to the unfamiliar nature of the objects that the children were shown.

Borke concluded that the potential for understanding the viewpoint of another was already present in children as young as 3 and 4 years of age, and this seems to be a reliable addition and revision to Piaget’s original assumption that children of this age are egocentric and incapable to taking the viewpoint of others. It now seems clear that although their perspective taking abilities may not be fully developed, they tend to make egocentric responses when they misunderstood the task, but when given the appropriate conditions, they show that they are capable of working out another’s viewpoint.

However, on a final note, it is important to also consider that Borke’s finding that children as young as three years can perform correctly in perspective-taking tasks stands in firm contrast to other researchers who have found that three-year-olds have difficulty realising another person’s perspective when the child and the other person are both looking at the same picture from different point of view [e.g. at the Louvres museum] (e.g., Masangkay et al, 1974).

(a) The Pre-Conceptual Period (2 – 4 years)… continued from above

Piaget use the three mountains task to investigate visual perspective taking and it was on the basis of this task that he concluded that young children were egocentric. There are also a variety of other perspective taking scenarios, and these include the ability to empathise with other people’s emotions, and the ability to know what other people are or may be thinking depending on the scene, setting and scenario (Wimmer and Perner, 1983). In other words, young children are less egocentric than Piaget initially assumed.

(b) The Intuitive Period (4 – 7 years)

At about the age of four, there is a further shift in thinking where the child begins to develop the mental operation of ordering, classifying and quantifying in a more systematic way. The term “intuitive” was particularly chosen by Piaget because the child is largely unaware of the principles that underlie the operations she completes and cannot explain why she has done them, nor can she carry them out in a fully satisfactory way, although she is able to carry out such operations involving ordering, classifying and quantifying.

Difficulties can be observed if a pre-operational child is asked to arrange sticks in a particular order. 10 sticks of different sizes from A (the shortest) to J (the longest), arranged randomly on a table were given to the children. The child was asked to arrange them in ascending order [order of length]. Some pre-operational children could not complete the task at all. Some other children arrange a few sticks correctly, but could not complete the task properly. And some put all the smaller ones in one and all the longer one in another. A more advance response was to arrange the sticks so that tops of the sticks when order even though the bottoms were not [See FIGURE C].

FIGURE C. The pre-operational child’s ordering of different-sized sticks. An arrangement in which the child has solved the problem of seriation by ignoring the length of the sticks.

To sum up, the pre-operational child is not capable of arranging more than a very few objects in the appropriate order.

It was also discovered that pre-operational children also have difficulty with class inclusion tasks – those that involve part-whole relations. Let us assume that a child is given a box that contains 18 brown beads and 2 white beads; all the beads are wooden. When asked “Are there more brown beads than wooden beads?” [note that the question does not make sense since all the beads are made of wood but some are brown and some are white], the pre-operational child tends to say that there are “more brown beads”. The child at the intuitive-period of the pre-operational stage finds it hard to consider the class of “all beads” [wooden] and at the same time considering the subset of beads, the class of “brown beads”[wooden + brown].

This findings is generally true for all children in the pre-operational stage, irrespective of their cultural background. Investigators further found that Thai and Malaysian children gave responses that were very similar to those of Swiss children at this stage of life [4 – 7 years old] and in the same sequence od development [the intuitive period].

Here, a Thai boy who was shown a bunch of 7 roses and 2 lotus [all are in the class of flowers], states that there are more roses than flowers [problem with class of all flowers] when prompted by the standard Piagetian questions:

Child: More roses.

Experimenter: More than what?

Child: More than flowers.

Experimenter: What are the flowers?

Child: Roses.

Experimenter: Are there any others?

Child: There are.

Experimenter: What?

Child: Lotus

Experimenter: So in this bunch which is more roses or flowers?

Child: More roses.

(Ginsburg and Opper, 1979, pp. 130-1)

One of the most extensively investigated aspects of the pre-operational child’s thinking processes is what Piaget called “conservation”. Conservation refers to the understanding that superficial changes in the appearance of a quantity do not mean that there has been any real change in the quantity. For example, if we had 10 dolls placed in line, and then they were re-arranged in a circle, it would not mean that the quantity has been altered [i.e. if nothing is added or subtracted from a quantity then it remains the same – conservation].

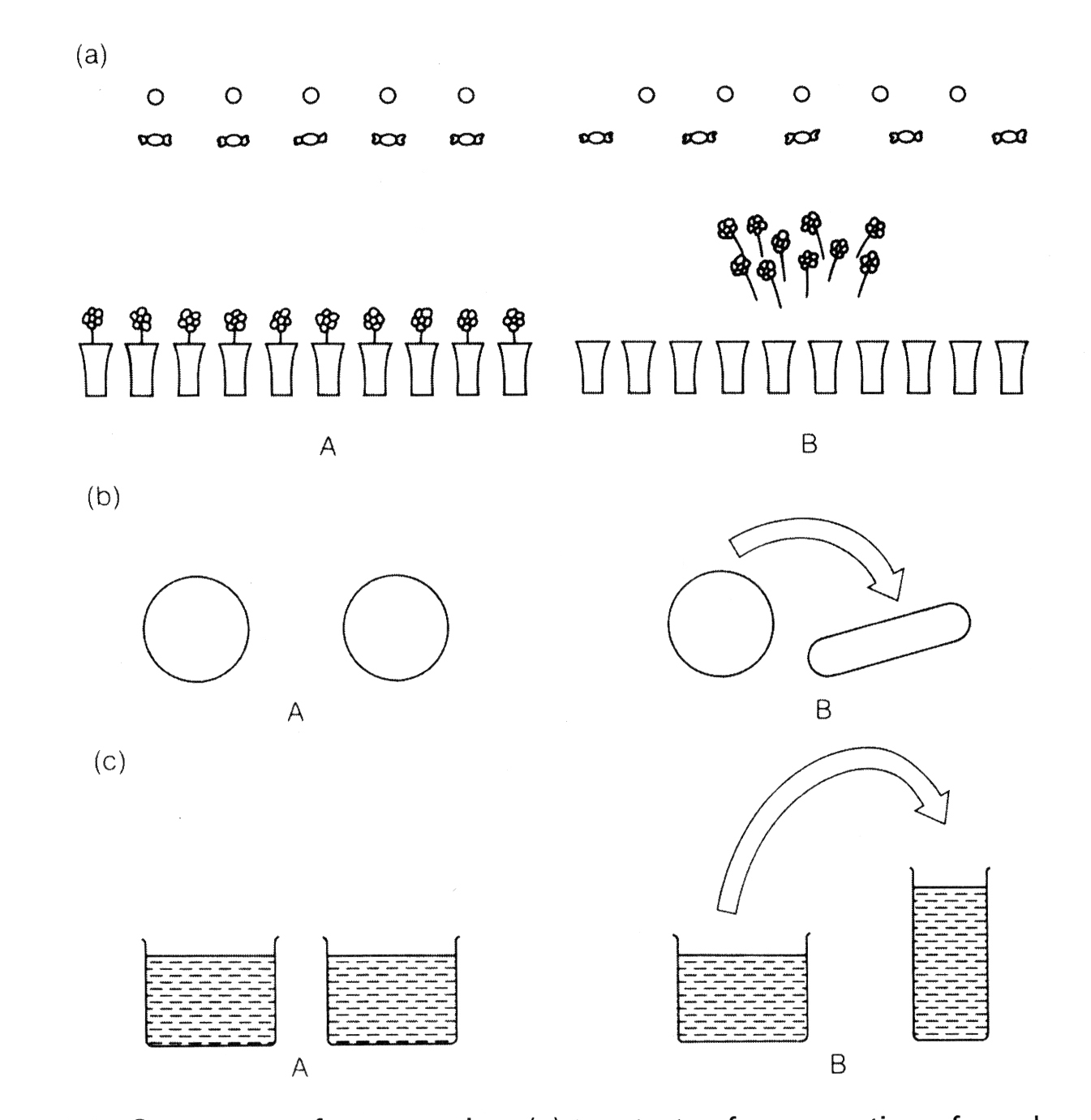

Piaget’s experiments revealed that children in the pre-operational stage generally find it hard to grasp the concept that an object’s qualities remain intact even if it is changed in shape and appearance. A series of conservation tasks were used in the investigations and examples are given in FIGURE D and PLATE A.

FIGURE D. Some tests of conservation: (a) two tests of conservation of number (rows of sweets and coins; and flowers in vases); (b) conservation of mass (two balls of clay); (c) conservation of quantity (liquid in glasses). In each case illustration A shows the material when the child is first asked if the two items or sets of items are the same and illustration B shows the way that one item or set of items is transformed before the child is asked a second time if they are still similar.

PLATE A. A 4-year-old puzzles over Piaget’s conservation of number experiments; he says that the rows are equal in number in arrangement (a), but not in arrangement (b) “because they’re all bunched together here”.

If 2 perfectly identical balls of clay are given to a child and if questioned about whether the quantity of clay being similar in both balls, the child will generally agree that it is. However, if one of the balls of clay is rolled and shaped into a sausage [see FIGURE D(b)], and the child is questioned again about whether the amount are similar, he/she is more likely to say that one is larger than the other. When asked about the reasons for the answer, they are generally unable to give an explanation, but simply say “because it is larger”.

Piaget suggested that a child has difficulty in a task such as this because she could only focus on one attribute at a time [e.g. if length is being focussed on, then she may think that the sausage shaped clay, being longer, has more clay it it. According to Piaget, for a child to appreciate that the sausage of clay has the same amount of clay as the ball would require an understanding that the greater length of the sausage is compensated for by the smaller cross section of the sausage. Piaget said that pre-operational children cannot apply principles such as compensation.

A further example to demonstrate this weakness in the child’s reasoning about conservation is through the sweets task [see FIGURE D(a)]. In this scenario, a child is shown 2 rows of sweets with a similar number of sweets in each row [presented with one to one layout] and when asked if the numbers match in each row, she will usually agree. Shortly after, one row of sweets is made longer by spreading them out, and the child is once again asked whether the number of sweets in similar in each row; the pre-operational child usually makes a choice between the rows suggesting that one has more sweets in it. He/she may for example think that the longer row means more objects [logic of the pre-operational child]. At this stage, the child does not realise that the greater length of the row of sweets is compensated for by the greater distance between the sweets.

Compensation is only one of several processes that can help children overcome changes in appearance; another process is known as “reversibility”. This is where the children could think of literally “reversing” the change; for example if the children imagine the sausage of clay being rolled back and reshaped into a ball of clay, or the row of sweets being pushed back together, they may realise that once the change has been reversed the quantity of an object or the number of items in the row remains similar to before. Pre-operational children lack the thought processes needed to apply principles like “compensation” and “reversibility”, and therefore they have difficulty in conservation tasks.

In the next stage, which is the third stage of development known as the “Concrete Operational Stage”, children will have achieved the necessary logical thought processes that give them the ability to use the required principles and handle conservation techniques and other problem-solving tasks easily.

Revisions of the Pre-Operational Stage

While Piaget claimed that the pre-operational child cannot cope with tasks like part-whole relations or conservations, because they lack the logical thought processes to apply principles like compensation. Other researchers have pointed out that children’s lack of success in some tasks may be due to factors other than ones associated with logical processes.

The pre-operational child seems to lack the ability to grasp the concept of the relationship between the whole and the part in class inclusion tasks, and will happily state that there are more brown beads than wooden beads in a box of brown and white wooden beads “because there are only two white ones”. Some other researchers have focussed their attention on the questions that children are asked during such studies and found them to be unusual [e.g. it is not often in every day conversation that we ask questions such as “Are there more brown beads or more wooden beads?”]

Minor variations in the wording of the questions that enhances and clarifies meaning can have positive effects on the child’s performance. McGarrigle (quoted Donaldson, 1978) showed children 4 toy cows, 3 black and 1 white, all were lying asleep on their sides. If the children were asked “Are there more black cows or more cows?” [as in a standard Piagetian experiment with a meaningless trap wording of the question] they tended not to answer correctly. McGarrigle found that in a group of children aged 6 years old, 25% answered the standard Piagetian question correctly, and when it was rephrased, 48% of the children answered correctly – a significant increase. From such an observation it was deduced that some of the difficulty of the task was in the wording of the question rather than just an inability to understand part-whole relations.

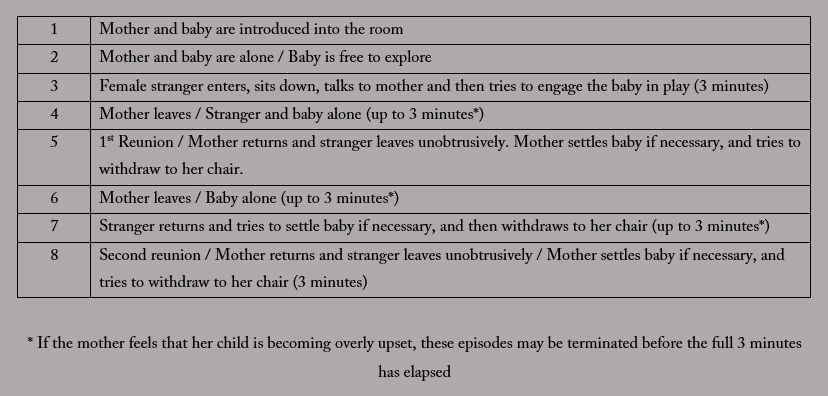

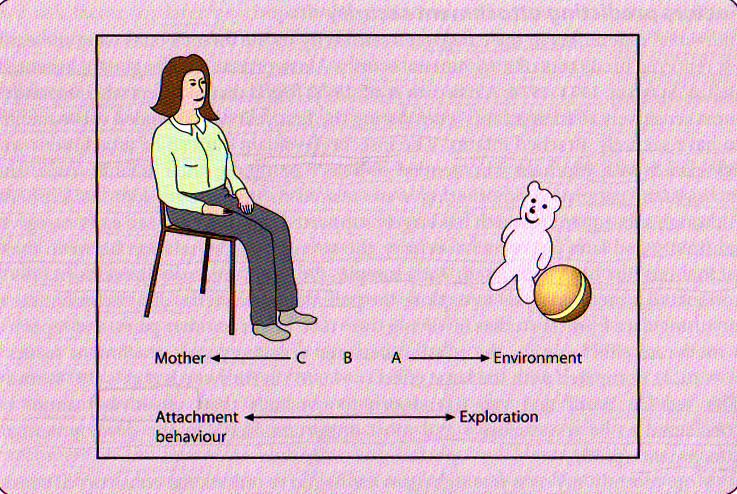

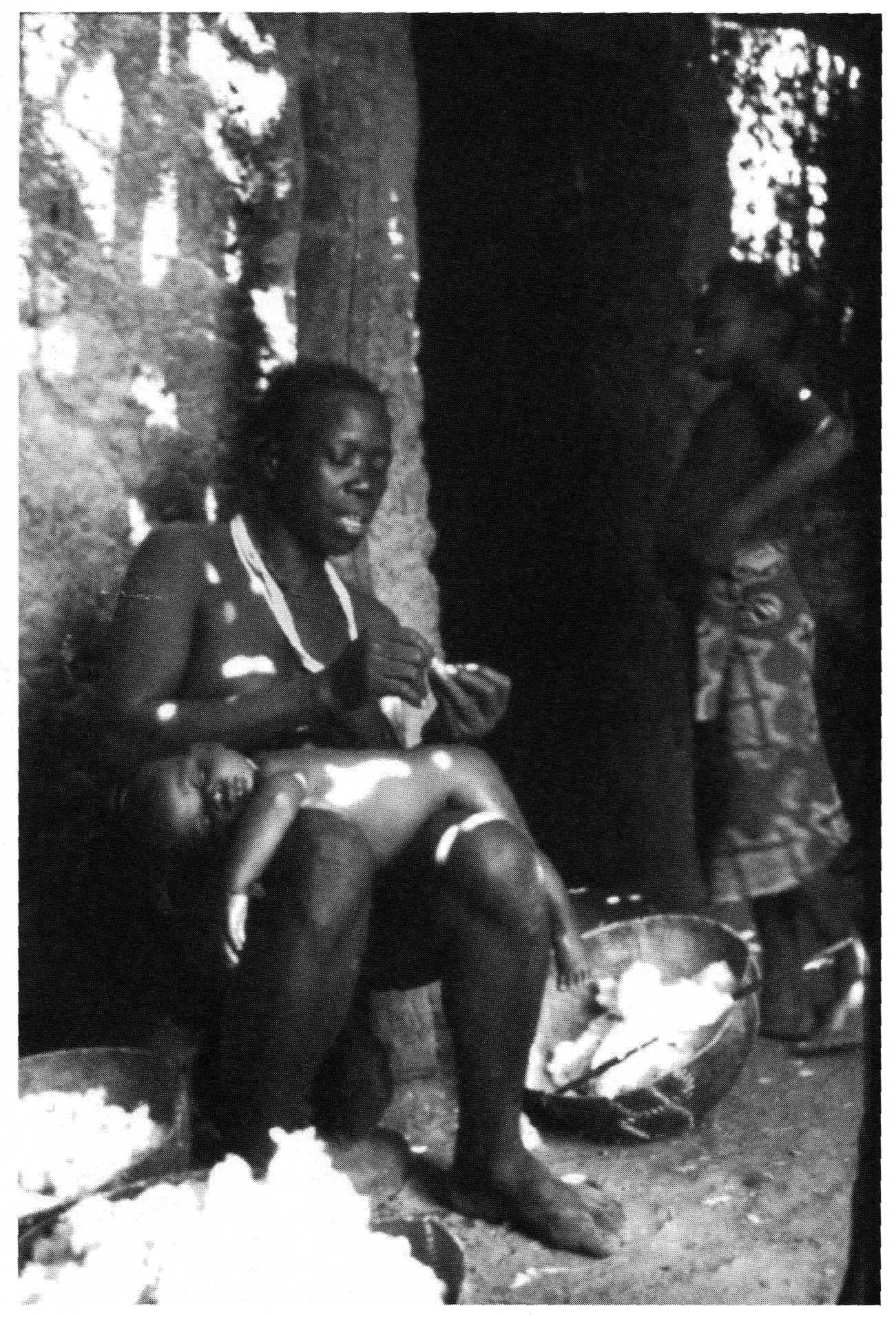

Donaldson (1978) put forward a different reason from Piaget as a cause for children’s poor performance in conservation tasks, he argued that children have a build in model of the world by formulating hypotheses that help them anticipate future events based on their past experiences. Hence, in the case of the child there is an expectation about any situation, and his/her interpretation of the words she hears will be influenced by the expectations she brings to the situation. When in a conservation experiment, for example, the experimenter asks a child if there are the same number of sweets in two rows [FIGURE D(a)]. Then one of the rows is changed by the experimenter while emphasising that it is being altered. Donaldson suggested that it is quite fair to assume that a child may be compelled to deduce that there would be a link between the change that occurred [the display change] and the following question [about the number of sweets in each row]; otherwise why would such a precise question come from an adult if there had not been any change? If the child is of the belief that adults only carry actions when they desire a change, then he/she might assume that a change has occurred.