Mis-à-jour le Mercredi, 25 Janvier 2023

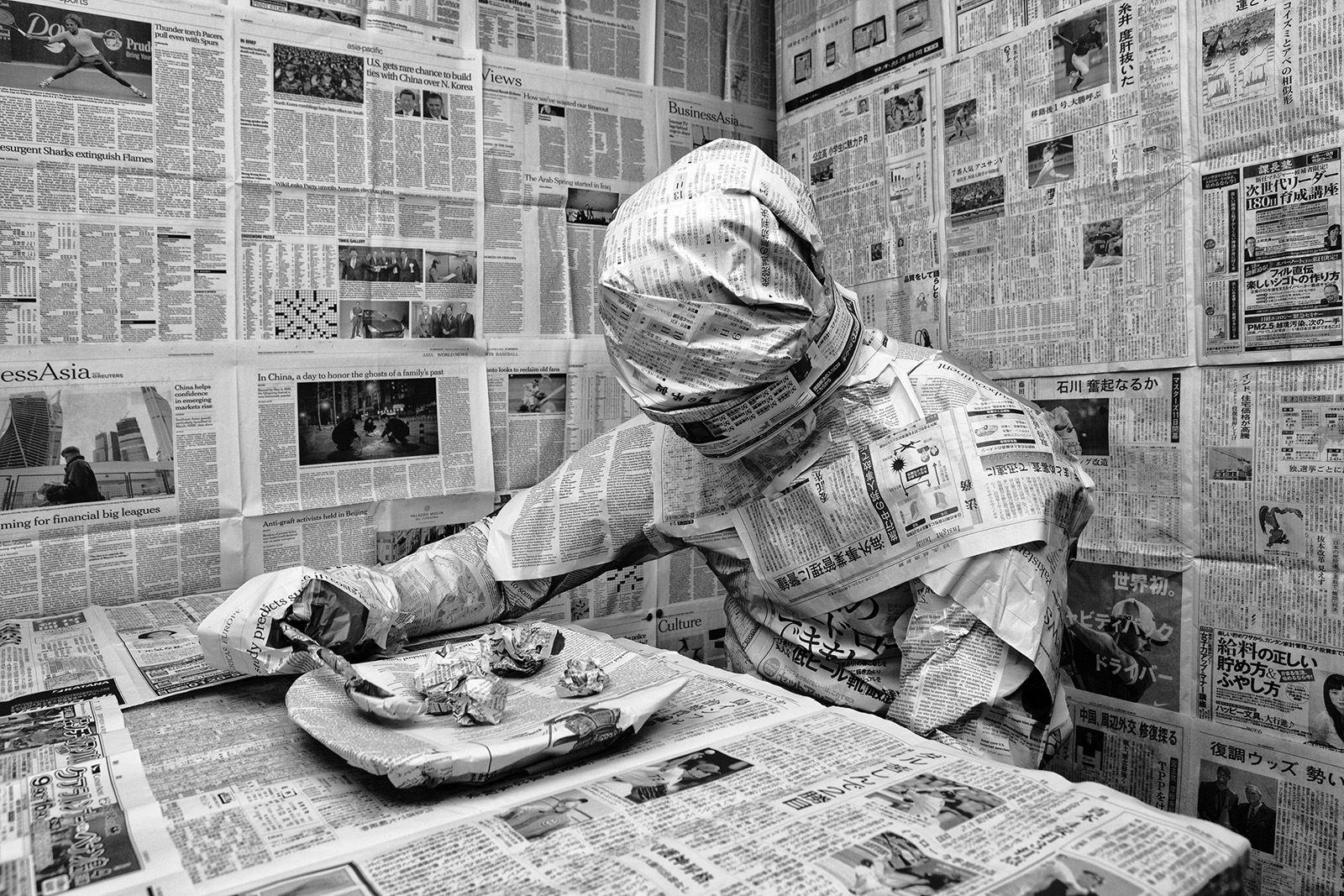

Photographie: Danny J. D’Purb © 2008

History and Background

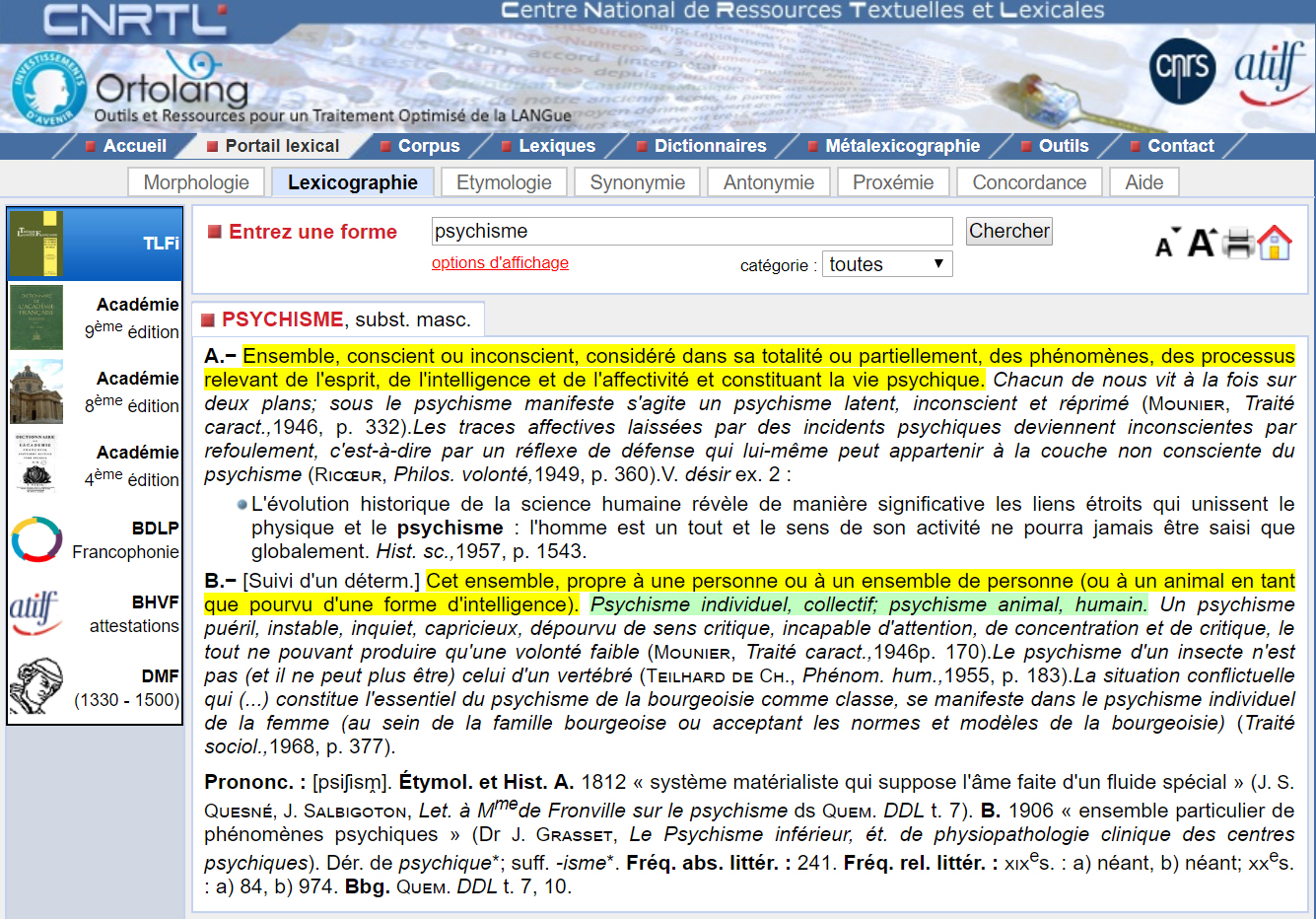

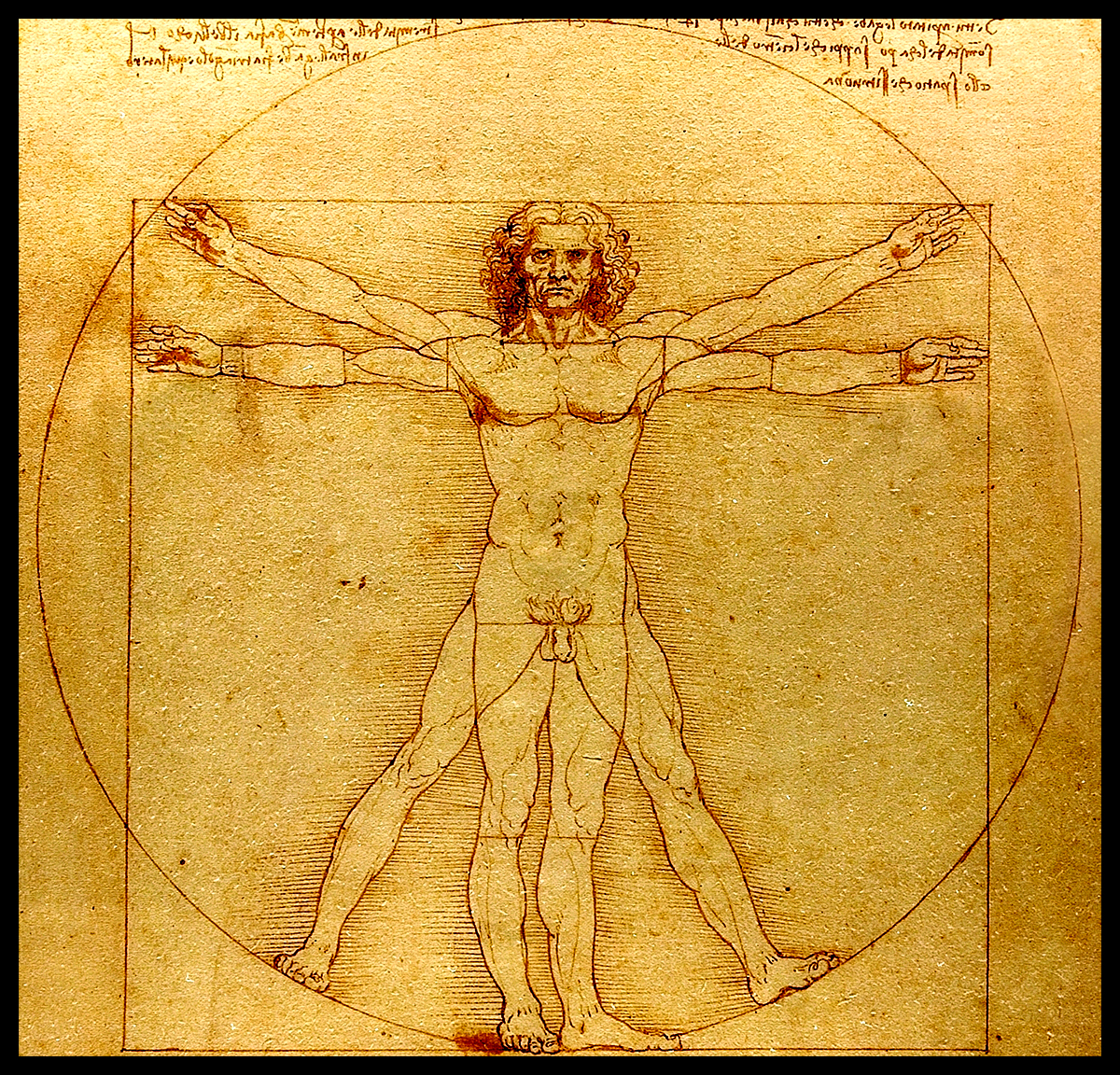

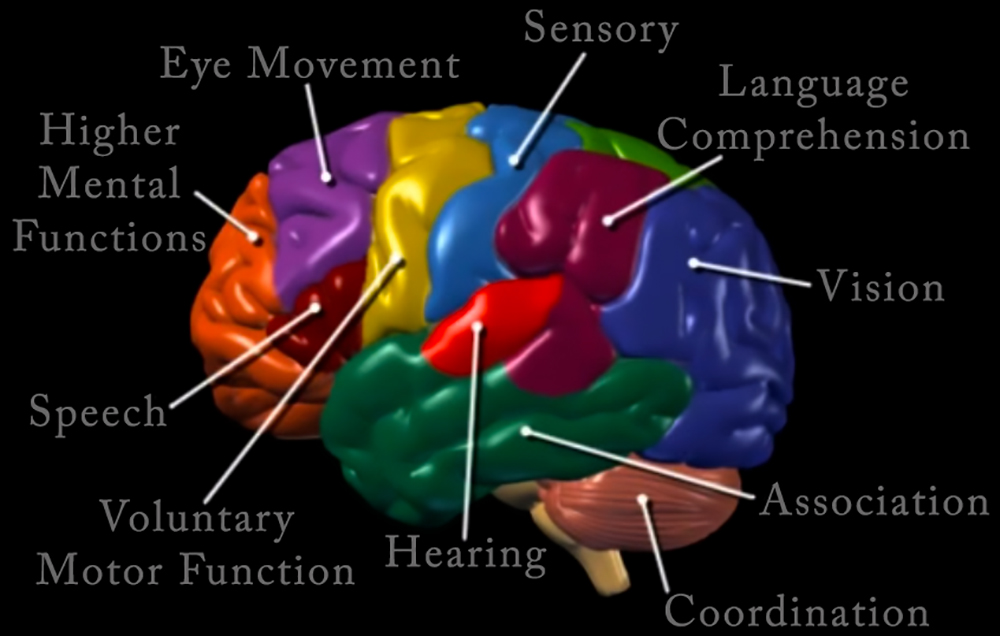

In contemporary psychology, the psychoanalytic movement’s place is both unique and paradoxical. Focussing on the study of the mind as a “software” running on the brain as the “hardware”, psychoanalysis remains the only discipline that truly focuses on the mechanism and processes behind our thoughts. Unlike empirical behavioural science and other “cogno-sciences” that can be fairly barbaric and obstinate in the forced application of the rigid mathematical and reductionist systematic procedures embedded in the classic scientific method when dealing with an entity as complex and organic as the human mind; psychoanalysis has remained focussed in understanding human psychology by capturing it in all its details, depths, dimensions and linguistic aspects.

The scientific method although a proven mathematical approach to inquiries in the hard sciences [e.g. biology, medecine, physics, chemistry, astrophysics, material science, astronomy, etc], shows its limitations when used as a tool for psychological inquiry in the measurement of variables that are incredibly hard to measure such as emotions, values, motives, desires, libidinous intensity or dreams. It is also fair noting that humans are different from simple organisms, molecules or robots, hence psychoanalysis remains the only discipline focused on the mind [the software] assuming that most human beings have a physiologically healthy brain [the hardware].

However, modern sciences have discovered how abnormalities in the brain’s physiology due to birth defects or injury may result in behavioural problems linked to a deficient mind due to the defective brain [hardware] at its disposal. Hence, nowadays most good intellectuals in the field of psychoanalysis would likely be a better psychologist with an in-depth knowledge of the physiology of the brain, i.e. the major areas affecting core functions such as speech [Wernicke and Broca’s], vision [the occipital lobe], and motor abilities [parietal lobe], etc.

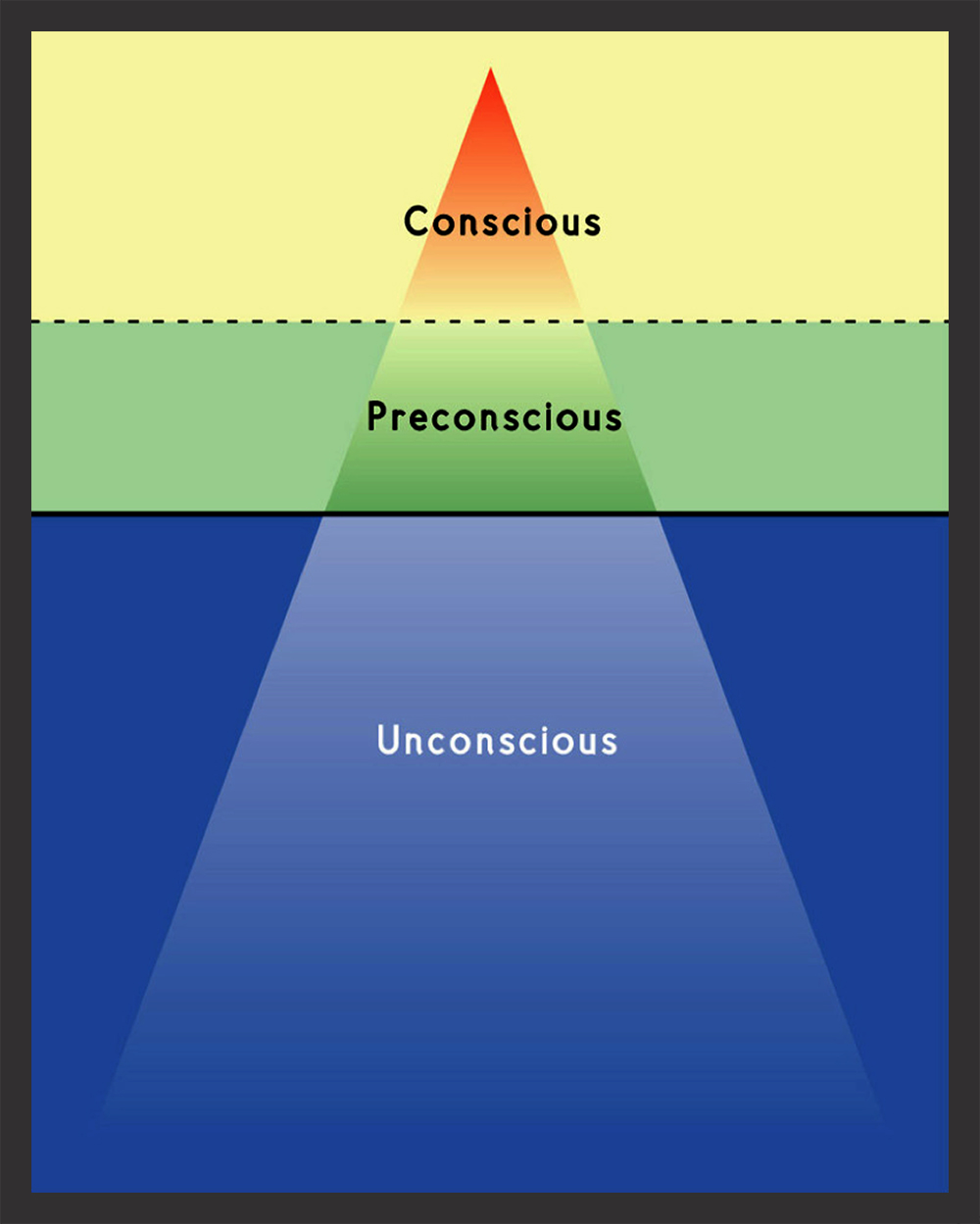

This is because some psychological problems may on rare occasion be caused by brain injuries or physiological abnormality due to virus, trauma, stroke or injury. In those cases where such a scenario materialises, the psychotherapist may refer the patient to a neurosurgeon who may be more appropriate to inspect the extent of the problems on the defective brain [hardware] which may lead to a clearer perspective of the limitations being imposed on the mind of the affected individual and how it impacts processes such as the conscious, the preconscious and the unconscious [based on Sigmund Freud’s 1st ground breaking theory of mental life, the Topographic Model, which was also adopted by Jacques Lacan who argued convincingly that post-Freudian psychoanalysts had swayed too far from the fundamental concepts and turned psychoanalysis into a confusing genre].

However, as we are in the developmental stages of conception of the organic theory, a theory that takes the focus on the individual organism’s creative ability to another level, we are going to remain focussed on the mind. The organic theory was inspired by the brain’s magnificent ability to learn any age, and thus give the individual human organism the ability and freedom to define, create, redefine, recreate and shape itself based on its inherited and acquired abilities, desires and personal constructionist developments throughout its life – yes, the individual does have choices and these impact the person’s internal working model of mental life and the person as a whole along with his or her environment.

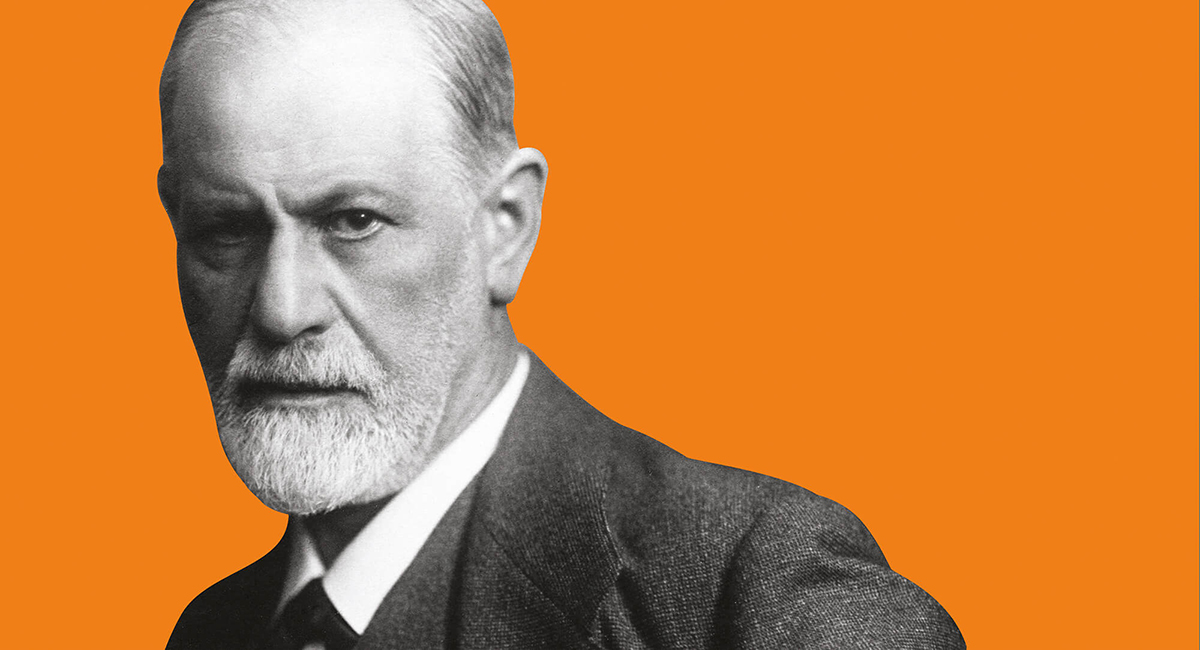

While psychoanalysis remains one of the most widely known schools of psychology it is perhaps not universally understood. The founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud is perhaps one of the most famous psychologist of the last century even if his chosen discipline, psychoanalysis, has little in common with the other schools of thought and psychology.

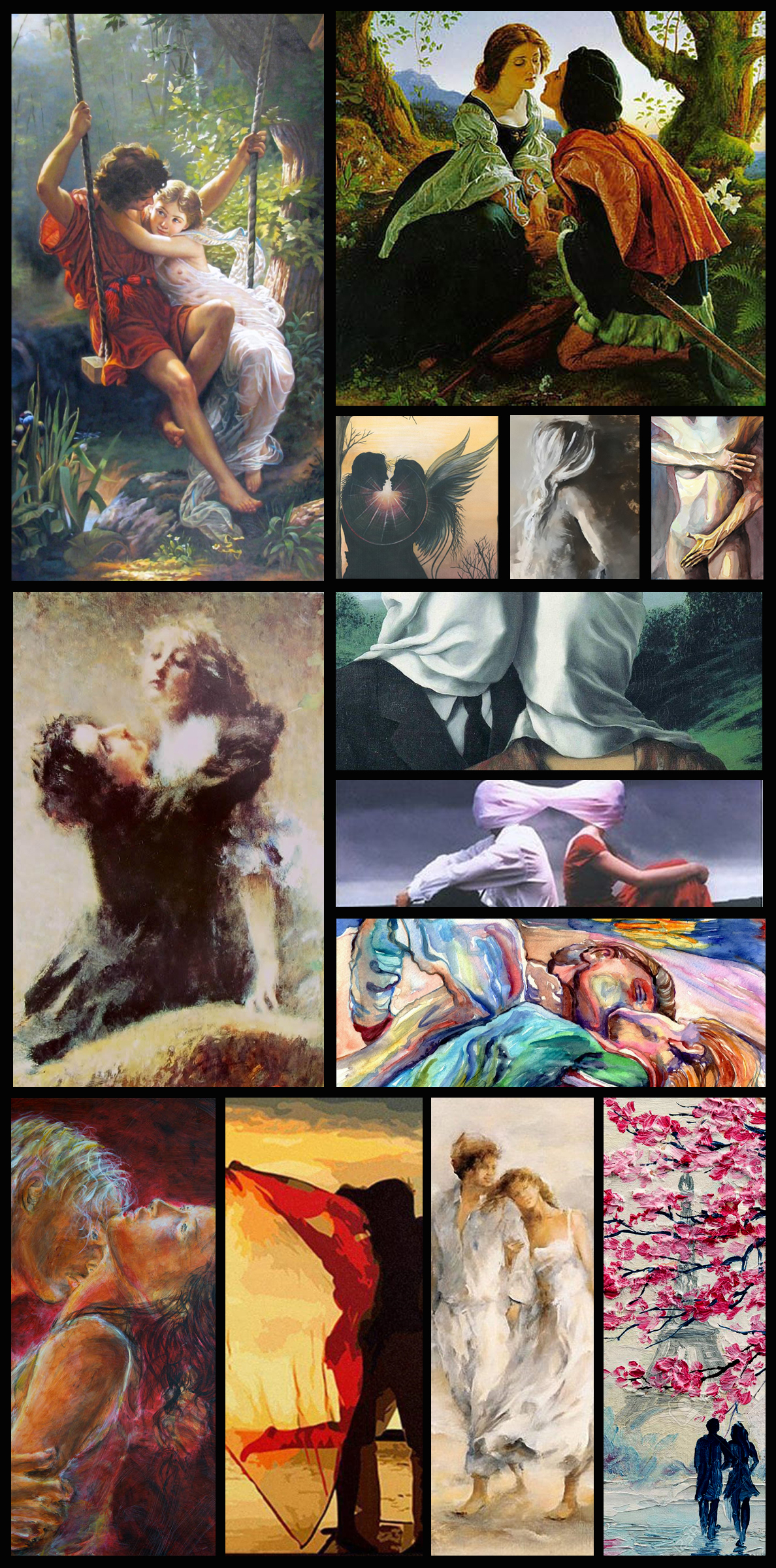

Psychoanalysis views the mind as an active, dynamic and self-generating entity, and this is in the German tradition of mental life [it was also a founding assumption for Jean Piaget as he developed his Theory of Cognitive Development in Children]. Freud saw psychoanalysis as a revolution of the mind that had to disturb the consciousness of the world, and viewed the unconscious as a reservoir of impulsive force repressed in the biological depths of the soul.

“Tête Raphaélesque Éclatée” par Salvador Dali (1951)

It is also important to note that Freud was trained in hard sciences, yet his system shows little appreciation for systematic and reductionist empiricism. As a physician, Freud used his observational skills to build his system within a medical framework, basing his theory on individual case studies. He did not depart from his understanding of 19th-century science in the effort to organise his observations, neither did he attempt to test his hypotheses rigorously through independent verification. As he testified, he was psychoanalysis and did not tolerate dissension from his orthodox views. Nevertheless, Freud had a tremendous impact on 20th century psychology, perhaps more importantly, the influence of psychoanalysis on Western thought, as reflected in literature, philosophy and art, significantly exceeds the impact of any other system and school of psychology.

The Active Mind

Photographie: Danny D’Purb © 2012

Going back to the philosophical foundations of modern psychology in Germany during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, we found that the tradition of Leibniz and Kant clearly emphasised mental activity. This is in contrast to British empiricism, which assumed the mind to be a passive entity [such as a sponge that simply soaks in what is thrown at it]. The German tradition held the most logical and creative assumption that the mind itself generates and structures human experience in characteristic ways [being “active”]. Whether through Leibniz’s monadology or Kant’s categories, the psychology of the individual could be understood only by examining the dynamic, inherent activity of the mind.

Throughout the years, as psychology evolved into an independent discipline in the latter part of the 19th century under Wundt’s tutelage, the British model of mental passivity served as a guiding philosophy. Clearly, Wundt’s empiricistic formulation was at odds with German philosophical precedents, recognised by both Stumpf and Brentano. Act psychology and the psychology of non-sensory consciousness represented by the Würzburg School were closer to the German philosophical assumptions of mental activity than to Wundt’s structural psychology. The Gestalt movement encompassed these alternatives to Wundt’s psychology in Germany. Eventually, as the rational outcome guided intellectuals, Wundt’s system was replaced by Gestalt psychology, turning into the dominant psychology in Germany prior to World War II – one based on a model of the mind that admitted inherent organisational activity.

The assumptions underlying mental activity in Gestalt psychology were highly qualified, where construct for mind involves the organisation of perception, based on the principle of isomorphism, which resulted in a predisposition toward patterns of personal-environmental interactions. The focus on organisation meant that the way of mental processes, not their content, was inherently structured. In other words, individuals were not born with specific ideas, energies, or other content in the mind; rather, the organisational structure was inherited to acquire mental contents in characteristic ways. Accordingly, the Gestalt movement, while rightly rejecting the rigidity of Wundt’s empiricistic assumptions and concepts, did not reject empiricism completely [as a technique to study some basic and easily defined variables (such as traits) and their relation(s) to others]. Instead, the Gestaltists advocated a compromise between the empiricist basis of British philosophy and the German model of activity. Consequently, this opened psychological investigation to the study of complex problem-solving and perceptual processes.

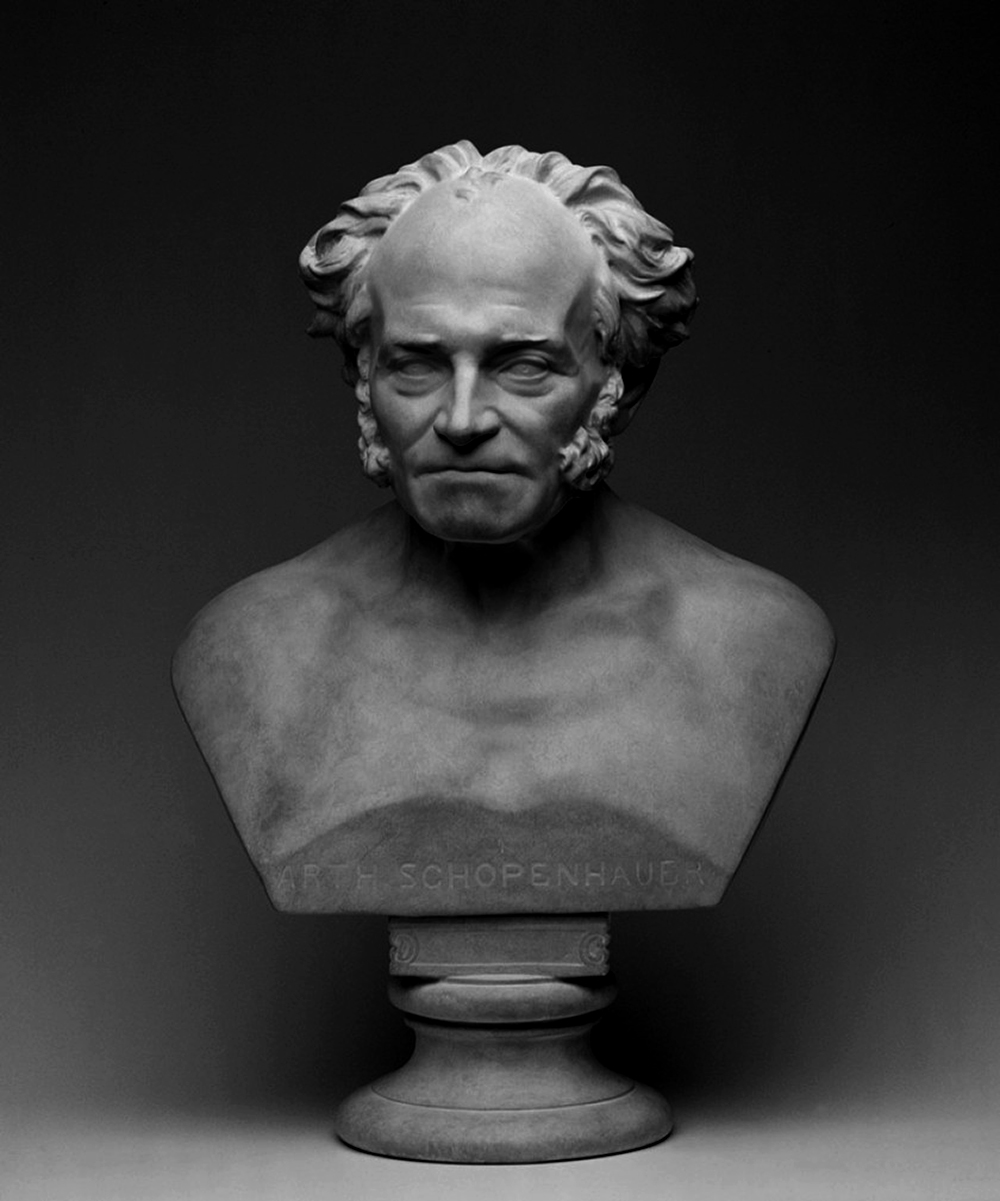

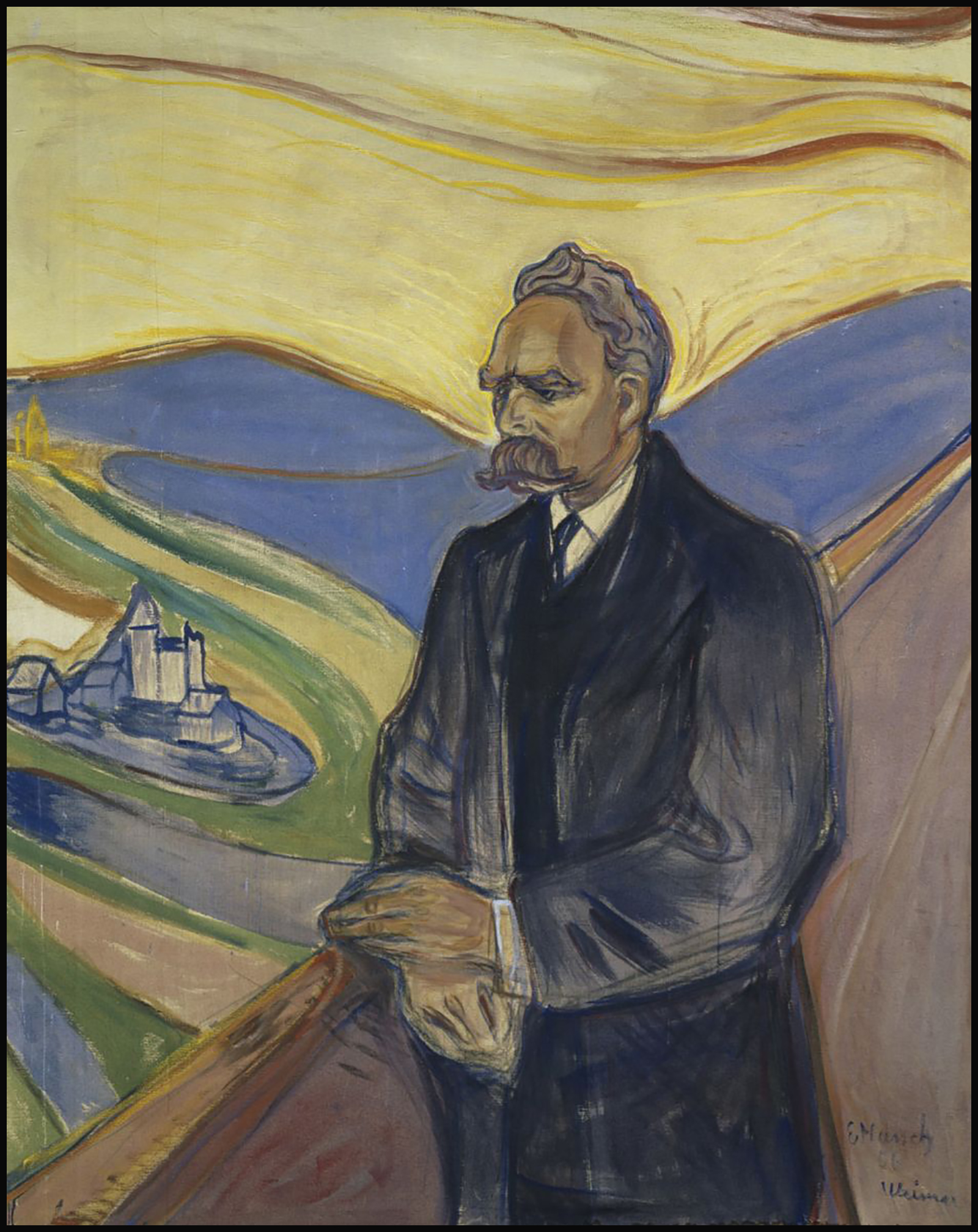

Consistent with the Gestalt foundations, psychoanalysis was firmly grounded in an active model of mental processes, however it shared little of the Gestalt commitment to empiricism. Freud’s views on personality were consistent not only with the activities of mental processing suggested by Leibniz and Kant, but also with the 19th century belief in conscious and unconscious levels of mental activity. In acknowledging the teachings of such philosophers as Von Hartman and Schopenhauer [Read the Essay on our Review of “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung”(The World as Will and Idea), Freud developed motivational principles that depended on energy forces beyond the level of self-awareness.

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860)

Moreover, for Freud, the development of personality was determined by individual, unconscious adaptation to these forces. The details of personality development as formulated by Freud are outlined below; however, is also important to recognise the fundamental basis of Freud’s thinking. Psychoanalysis is based on the implication of mental activity further than any other system of psychology. As a major representative of a reliance on mental activity to account for personality, psychoanalysis is set apart from other movements in contemporary psychology. In addition, psychoanalysis unlike the other branches of psychology, did not emerge from reductionist empirical research that stubbornly tries to apply mechanical scientific methodology to measure complex non-physical abilities; rather it was the product of the applied consequences of clinical practice [i.e. it was a force that was born on the field to treat mental problems as they surfaced throughout human history].

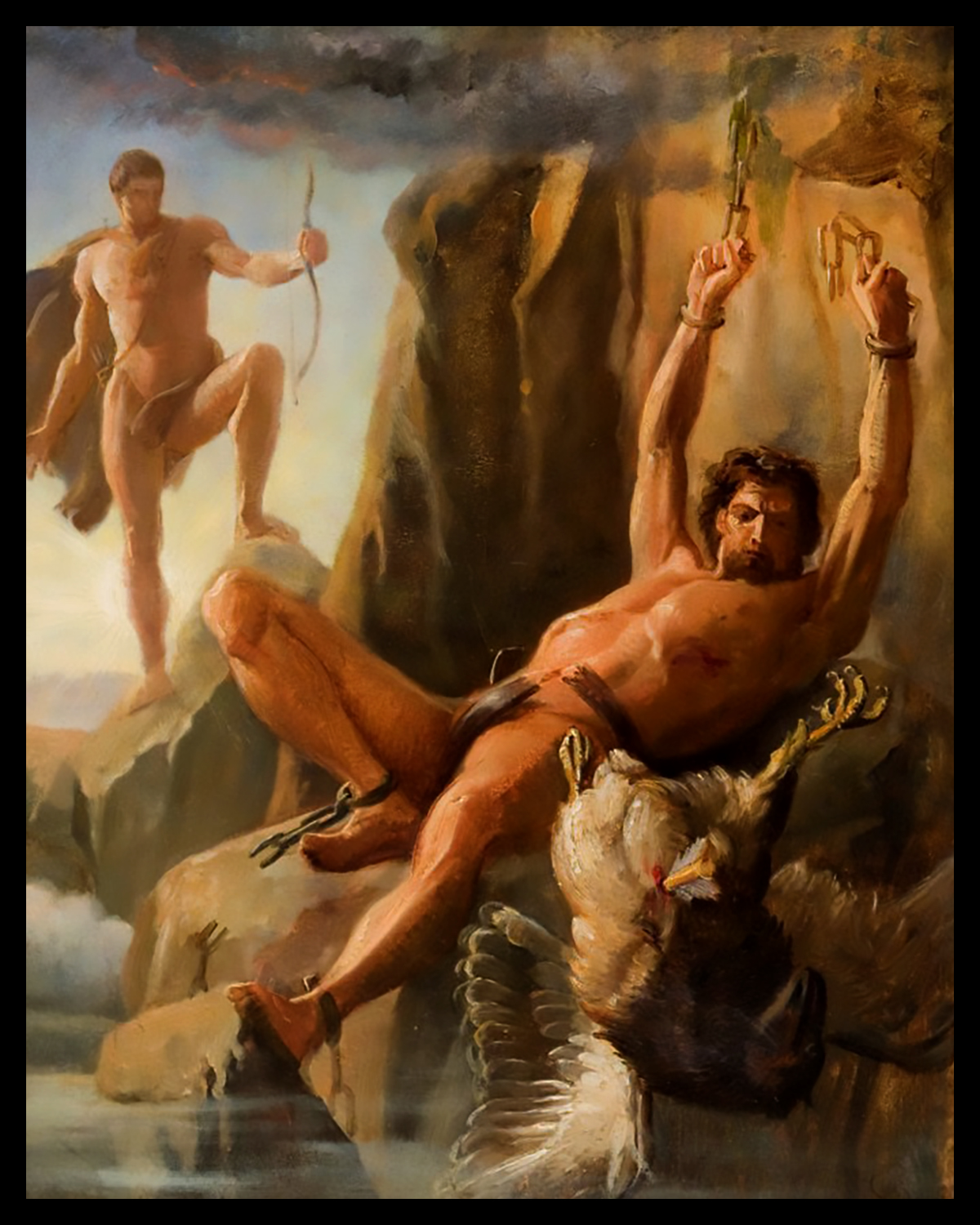

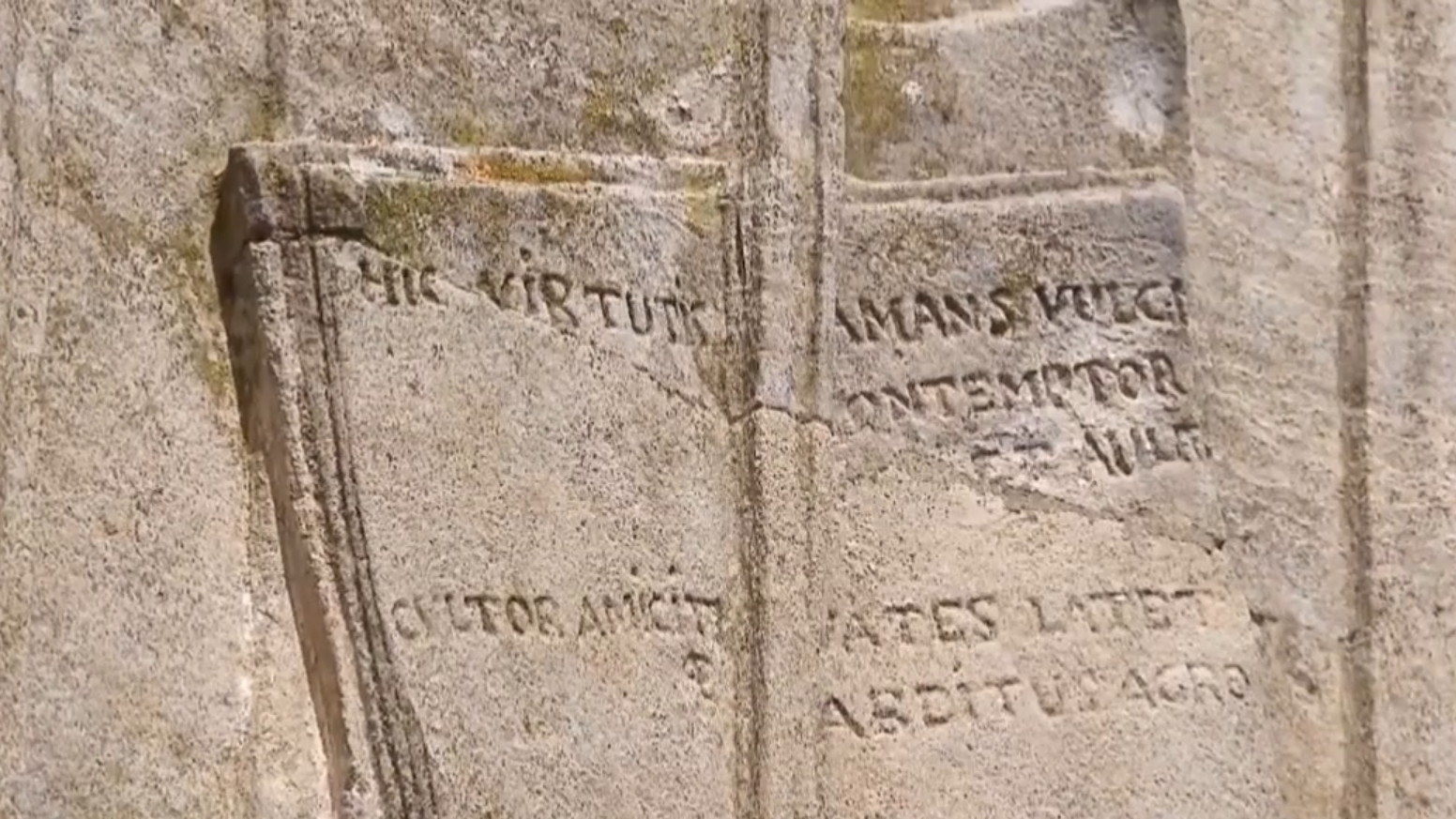

The Treatment of Mental Illness

Besides being the founder of the psychoanalytic movement in modern psychology, Freud is also remembered for his efforts in pioneering the upgrade in the treatment of mental and behavioural abnormalities, and was instrumental in psychiatry’s recognition as a branch of medicine that specifically deals with psychopathology. Before Freud’s works in attempting to devise effective methods of treating the mentally ill, individuals who deviated from socially acceptable norms were usually treated as if they were criminals or demonically possessed. Although shocking controversies in the contemporary treatment of mental deviancy appear occasionally, not too long ago such abuses were often the rule rather than the exception.

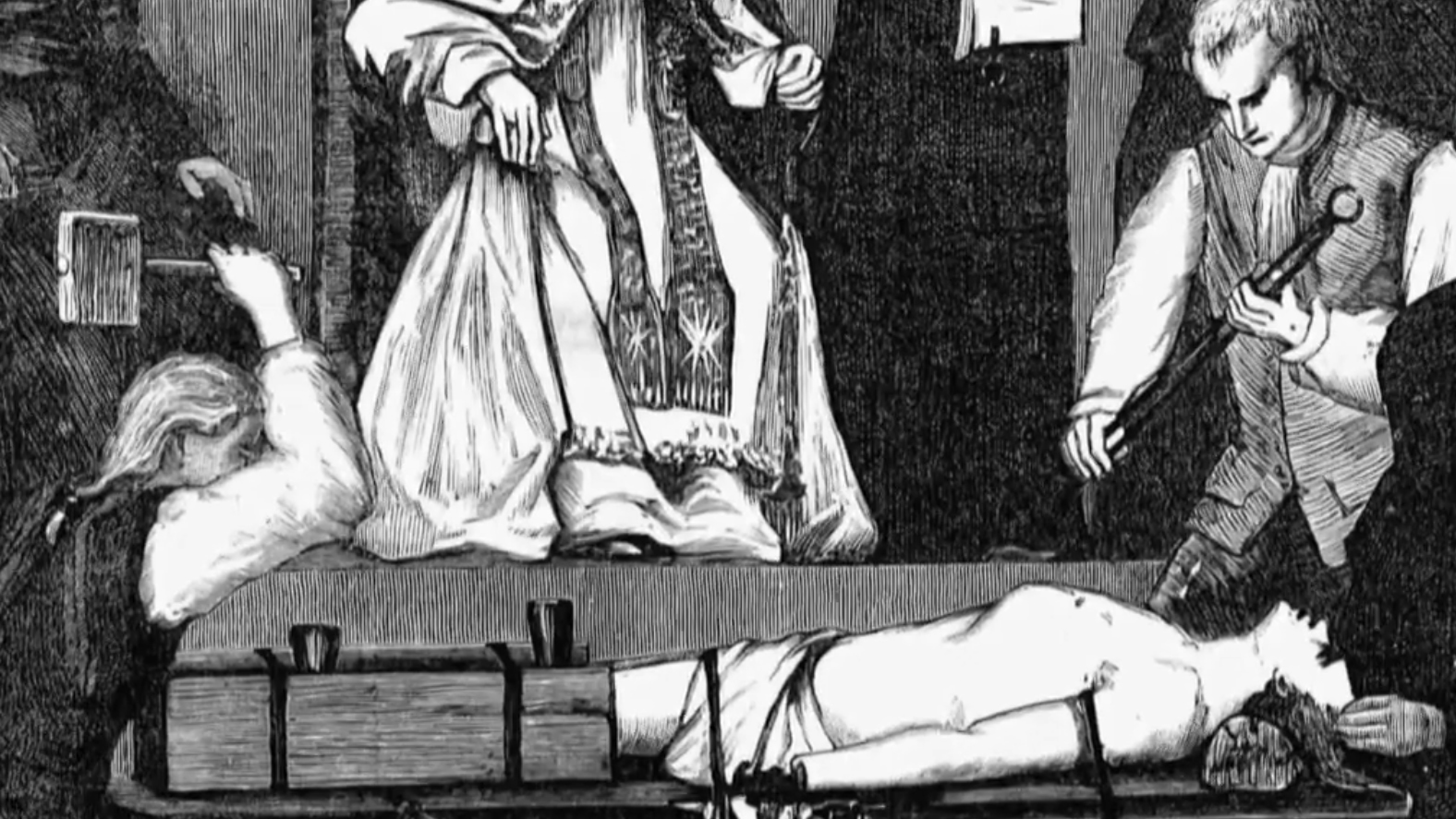

The treatment of mental illnesses was never a pleasant chapter in Western civilisation and it has been pointed out many times that abnormal behaviour is often mixed up with criminal behaviour as with heresy and treason. Even during the period of enlightenment during the European Renaissance, the cruelties and tortures of the inquisition were readily adapted to treat what we nowadays qualify as mental illness. Witchcraft continued to offer a reasonable explanation to such eccentric behaviour until recent times. Prisons were established to house criminals, paupers, and the insane without any differentiation. Mental illness was viewed as governed by evil or obscure forces, and the mentally ill were looked upon as crazed by such weird influences such as moon rays. Lunatics or “moonstruck” persons, were appropriately kept in lunatic asylums. As recently as the latter part of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the institution of for the insane in Utica, New York, which was progressive by the standards of the time, was called the Utica Lunatic Asylum. The name reflected the prevailing attitude toward mental illness.

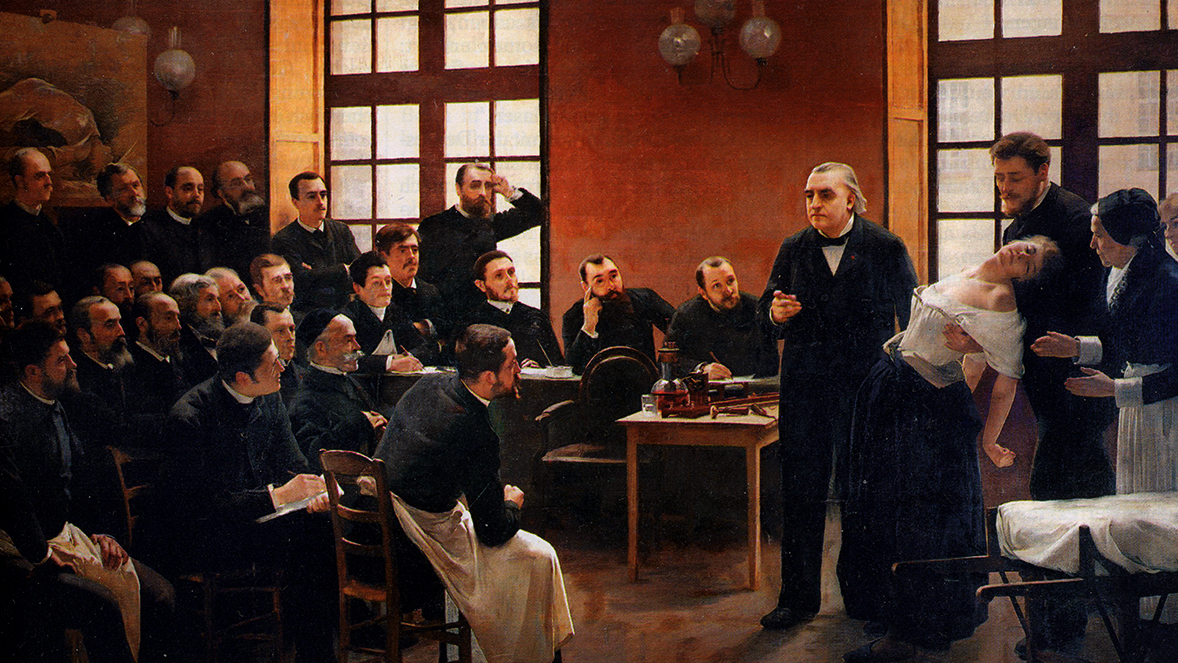

“Dr. Philippe Pinel at the Salpêtrière”, 1795 by Tony Robert-Fleury. Pinel ordering the removal of chains from patients at the Paris Asylum for insane women

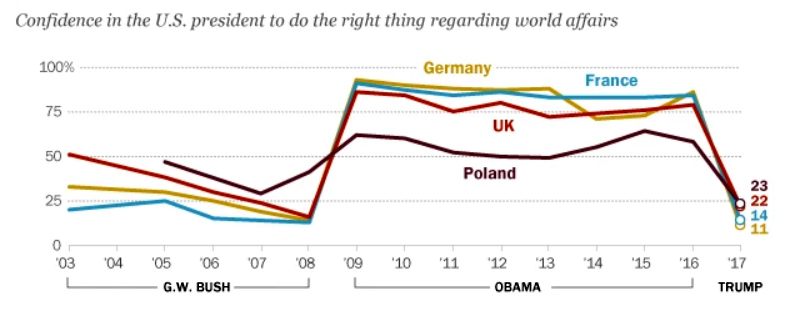

Reforms in the treatment of the institutionalised insane were slowly introduced during the 19th century. In 1794, Philippe Pinel (1745 – 1826) was appointed the chief of hospitals for the insane in Paris, and managed to improve both the attitude toward and the treatment of the institutionalised insane. In the United States, Dorothea Dix (1802 – 1887) accomplished the most noticeable reforms in the treatment of the mentally ill. Beginning in 1841, Dix led a campaign to improve the condition of indigent, mentally ill persons kept in jails and in poorhouses. However, these reforms succeeded in improving only the physical surroundings and maintenance conditions of the mentally ill; legitimate treatment was minimal. [Even today, in 2019, the US seems to have more people with eccentric behaviours and with questionable mental stability, for example, Donald Trump, who has been singled out as being mentally ill by more than one. See: (1) The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, (2) Trump Is ‘Mentally Ill’ Says Former Vermont Governor and Doctor Howard Dean, (3) American psycho? Donald Trump’s mental health is still a question, (4) Psychiatrist: Trump Mental Health Urgently Deteriorating & (5) Stanford’s Zimbardo asks: Is President Trump mentally ill?

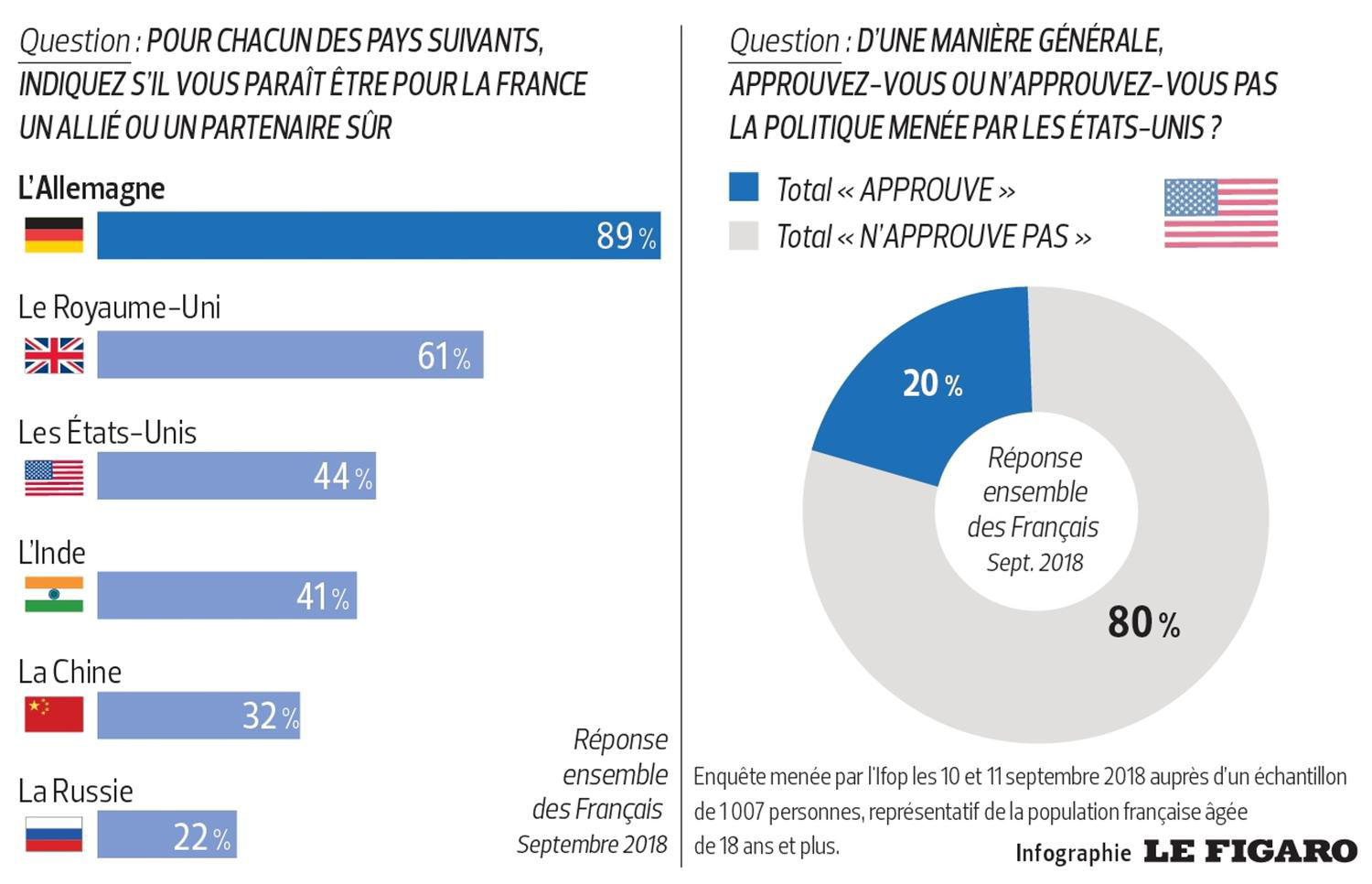

Around the world, favorability of the U.S. and confidence in its president decline / Source: Pew Research Center

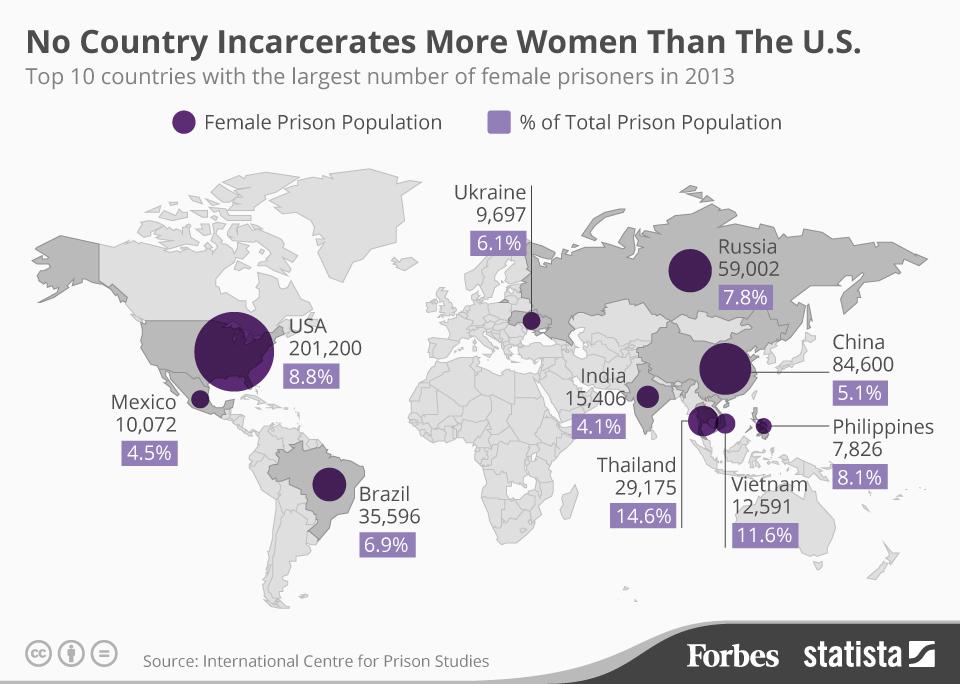

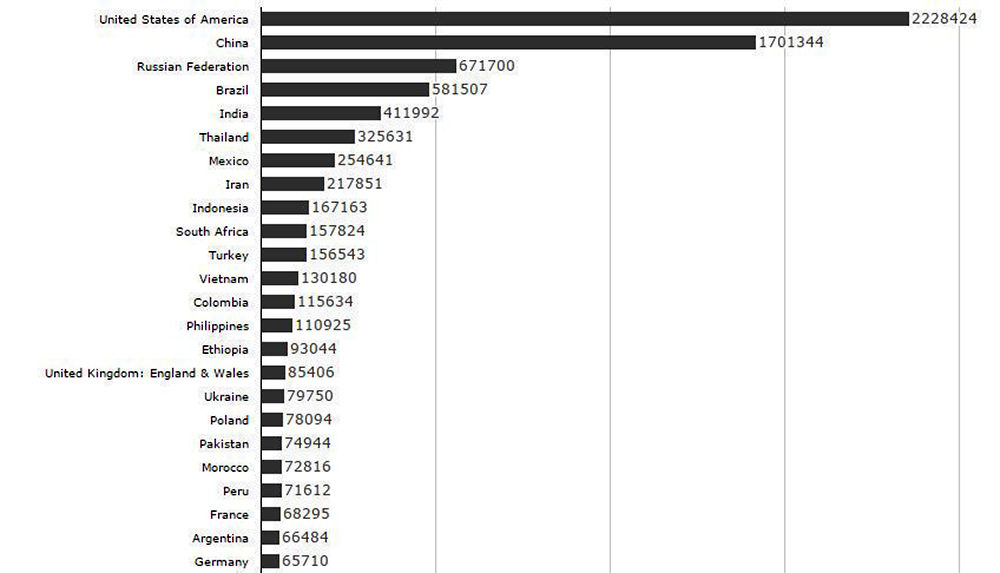

According to the International Centre for Prison Studies, nearly a third of all female prisoners worldwide are incarcerated in the United States of America. There are 201,200 women in US prisons, representing 8.8 percent of the total American prison population. / Source: Forbes

Highest to Lowest – Prison Population Total / Source: World Prison Brief

Efforts to develop comprehensive treatments were plagued by various quacks, such as the pseudoscience developed by Mesmer that dealt with the “animal spirit” underlying mental illnesses [although it may be true today if expressed as a metaphorical description to some of the behavioural manifestations of some mental disorders in some individuals].

“White Dogs and Tootsie Pops” by Marie Hughes

Similarly, the phrenology of Gall and Spurzheim advocated a physical explanation based on skull contours and localisation of brain functions – which was of course also wrong.

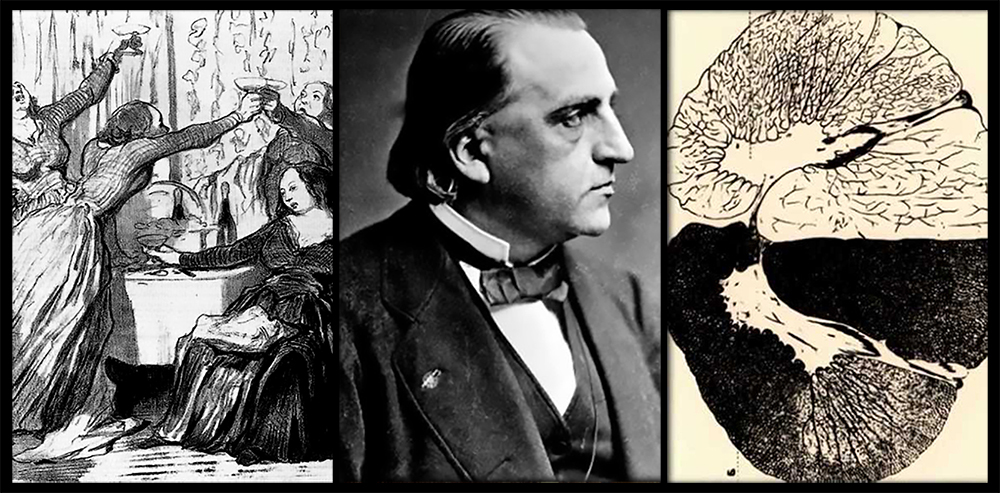

Gradually however, attempts were made to develop legitimate and effective techniques to treat emotional and behavioural abnormalities. One of the more productive investigations involved hypnotism and was pioneered by a French physician, Jean Martin Charcot (1825 – 1893). Charcot gained widespread fame in Europe, and the young Freud amazed by his abilities, studied under him, as did many other talented physicians and physiologists. He treated hysterical patients with symptoms ranging from hyper-emotionality to physical conversions of underlying emotional problems that the patient could not confront when conscious.

“Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière (1887)” with Jean Martin Charcot in Front (A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière) par André Brouillet à l’Université Paris Descartes

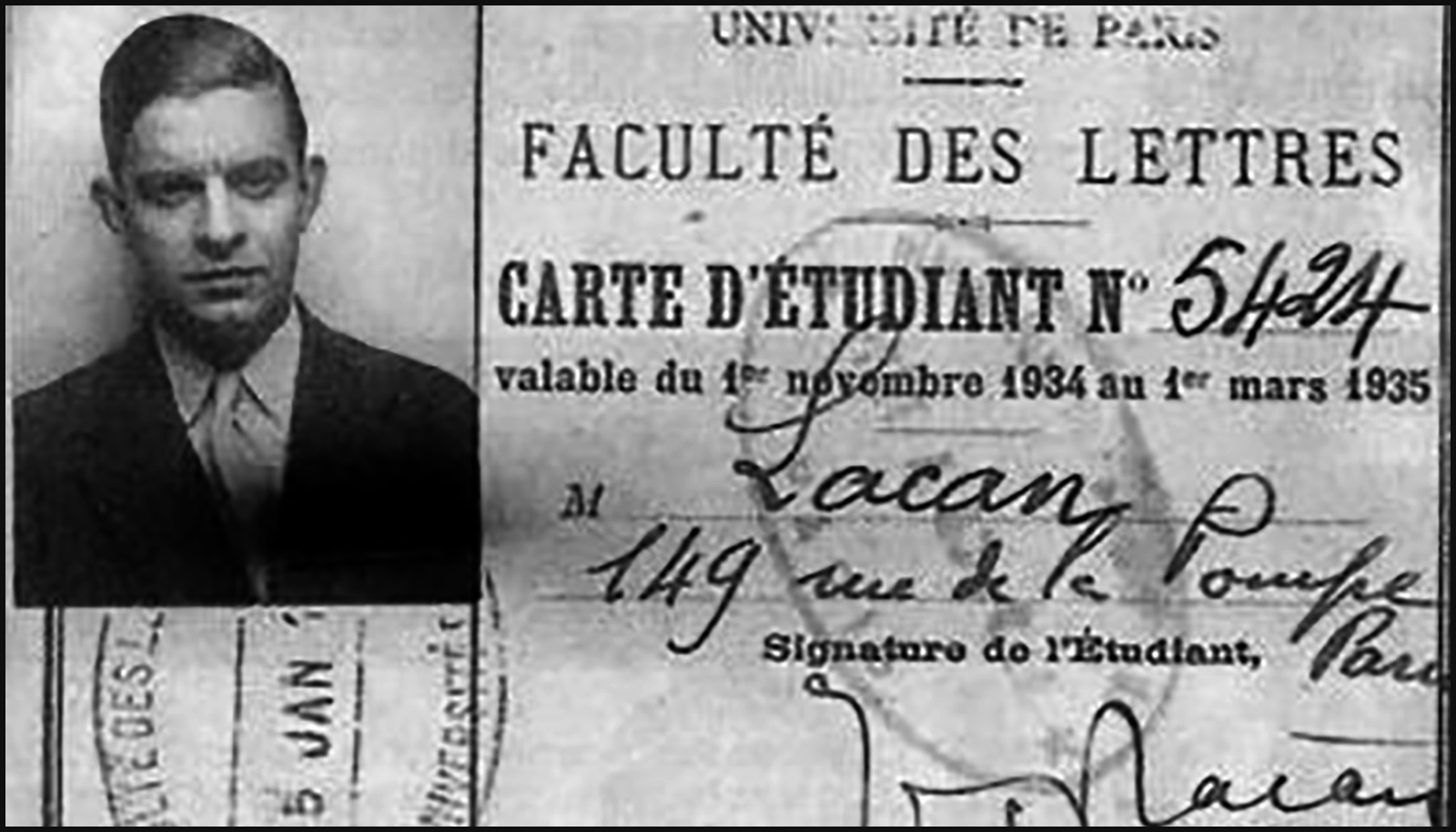

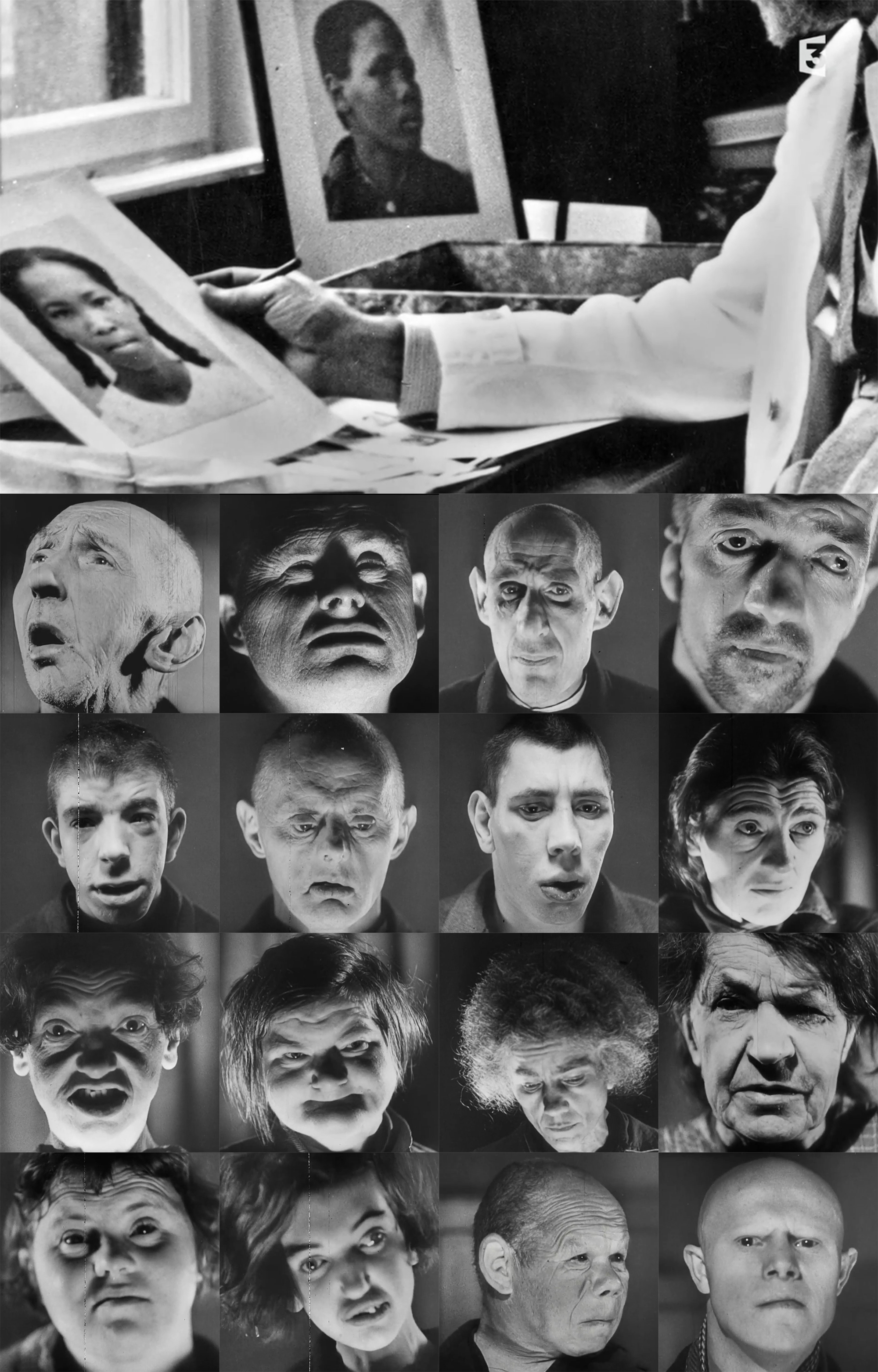

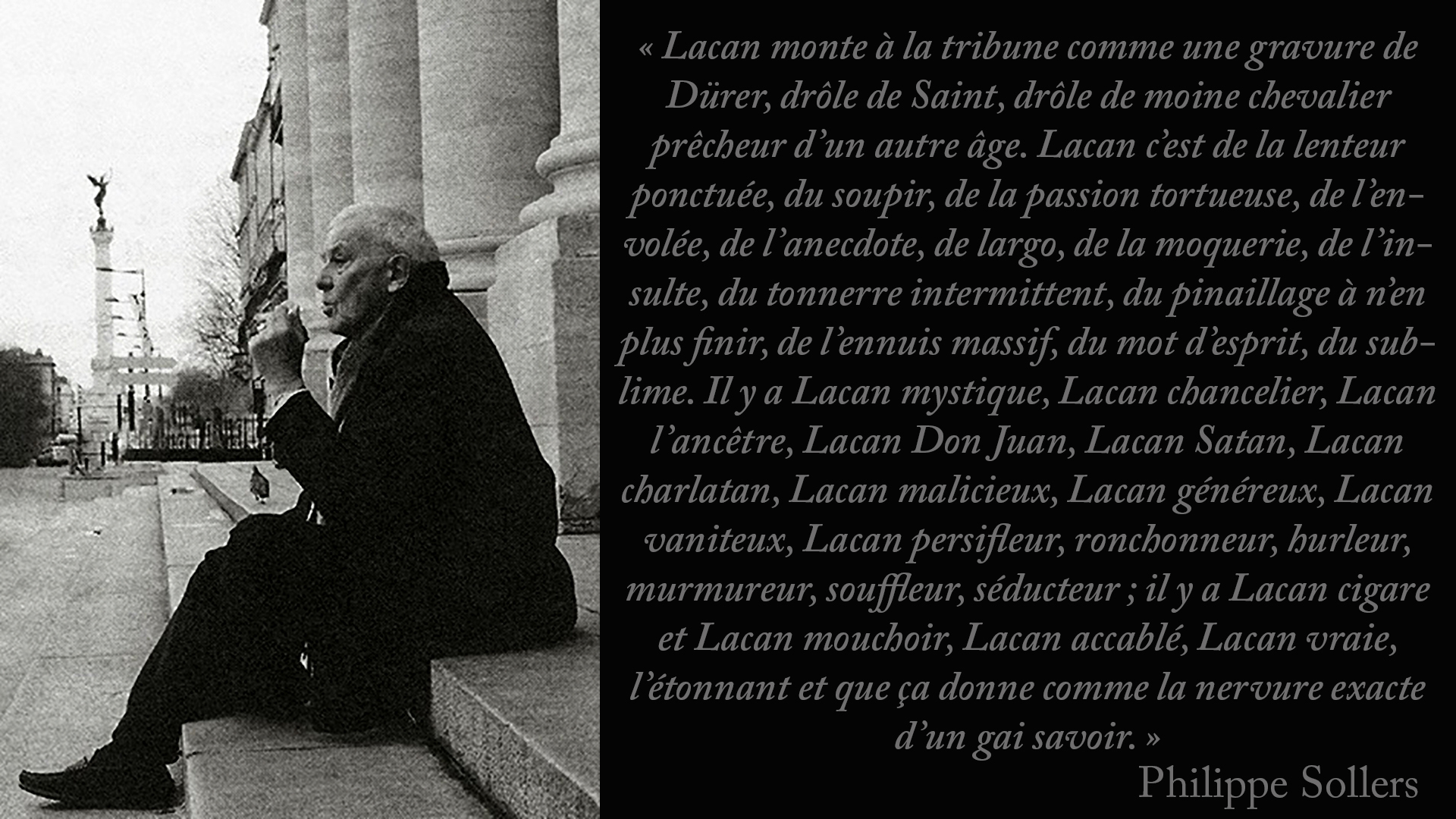

Another French physician in Nancy, namely Hippolyte Bernheim (1837 – 1919), developed a sophisticated analysis of hypnosis as a form of treatment, using underlying suggestibility to alter the intentions of the patient. Finally, Pierre Janet (1859 – 1947), a student of Charcot, used hypnotism to resolve the forces of emotional conflict, which he believed were basic to hysterical symptoms. However, it was Sigmund Freud who went beyond the techniques of hypnotism to develop a comprehensive theory of psychopathology from which systematic treatments evolved. Later, Jacques Lacan (1901 – 1981) would pulverise the tradition inherited from hospital medecine which consisted of displaying a patient before an audience of practitioners or students and asking questions whose deeper meaning was supposed to escape the patient. The actors in this ceremonial, the patients, trained by years of confinement, actually produced all the symptoms that the masters of the asylum expected of them. Lacan shattered this clinic with his gaze in order to give a voice to the mentally ill. Jean-Bertrand Pontalis said: “Lacan était extraordinairement courtois avec ses malades, les traitant pas du tout comme des patients d’asile – c’est la moindre des choses, mais ce n’est pas toujours le cas – comme des êtres humains et les amenaient peu à peu, créant une atmosphère de confiance, à les laisser parler très très librement. Pour l’anecdote, c’est assez savoureux, je me souviens qu’une fois il y avait une femme qui était paranoïaque qui se plaignait qu’on l’a suivi partout, « On me suit, on me suit, on me suit, on me suit partout… », Lacan à la fin lui dit, « Ne vous inquiéter pas chère madame, je vais trouver quelqu’un pour vous suivre » entendant par la, un médecin qui pourra lui traiter. Comme si lui-même, dans ces années-là était en train d’inventer et de s’inventer. Nous participions en accord avec lui en résonance avec lui à un mouvement inventif.” [French for: “Lacan was extraordinarily courteous with his patients, treating them not at all like asylum patients – to say the least but this is not always the case – like human beings and gradually, creating an atmosphere of trust, he led them to let them speak very, very freely. For the anecdote, it’s quite tasty, I remember that once there was a woman who was paranoid complaining that she was followed everywhere, “They follow me, they follow me, they follow me, they follow me everywhere…”, Lacan at the end said to her, “Don’t worry dear lady, I’ll find someone to follow you” hearing by this, a doctor who will be able to treat her. As if he himself, in those years, was in the process of inventing and inventing himself. In agreement with him, we were participating in an inventive movement in resonance with him.”]

A Biography of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939) / Image: Freud Museum London

Since psychoanalysis as we know it today is hugely influenced by the foundations laid by Sigmund Freud, it is worthwhile to have an understanding about the major points in his life. Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939) was born on the 6th of May 1856 in Freiberg, Moravia, at that time a norther province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today a part of the Czech Republic.

Freud was the eldest of 8 children, and his father was a relatively poor and not very successful wool merchant. When his business failed, Freud’s father moved with his wife and children [as many jews are accustomed to migrating to better places in the quest for a better life and income] first to Leipzig and then to Vienna when Freud was 4 years old. The young Freud remained in Vienna for most of the rest of his life, and his precocious genius was recognised by his family, and he was allowed many concessions and favours not permitted to his siblings. For example, young Freud was provided with better lighting to read in the evening, and when he was studying, noise in the house was kept to a minimum so he would not be disturbed.

Freud’s interest were varied and intense, and he showed an early inclination and aptitude for various intellectual pursuits. Unfortunately, Freud was a victim of the 19th century Jew-dislike which was obvious and severe in central and Eastern Europe after the numerous accounts of Jews being banished from places all over Europe due to their occult and violent religious practices on Christian infants [e.g. human sacrifices] along with their known habits in monopolising the majority of the press businesses to then distort news and heritage to their agendas and economic advantage.

However, although Freud was an atheist and more scientifically minded, his Jewish birth precluded certain career opportunities, most notably an academic career in university research. Indeed, medicine and law were the only professions open to Vienna Jews.

Freud’s early reading of Charles Darwin intrigued and impressed him to the point that a career in science was most appealing. The closest path that he could follow for training as a researcher was an education in medicine. Hence, Freud entered the university of Vienna in 1873 at the age of 17. However, because of his interests in a variety of fields and specific research projects, it took him 8 years to complete the medical coursework that normally required 6 years.

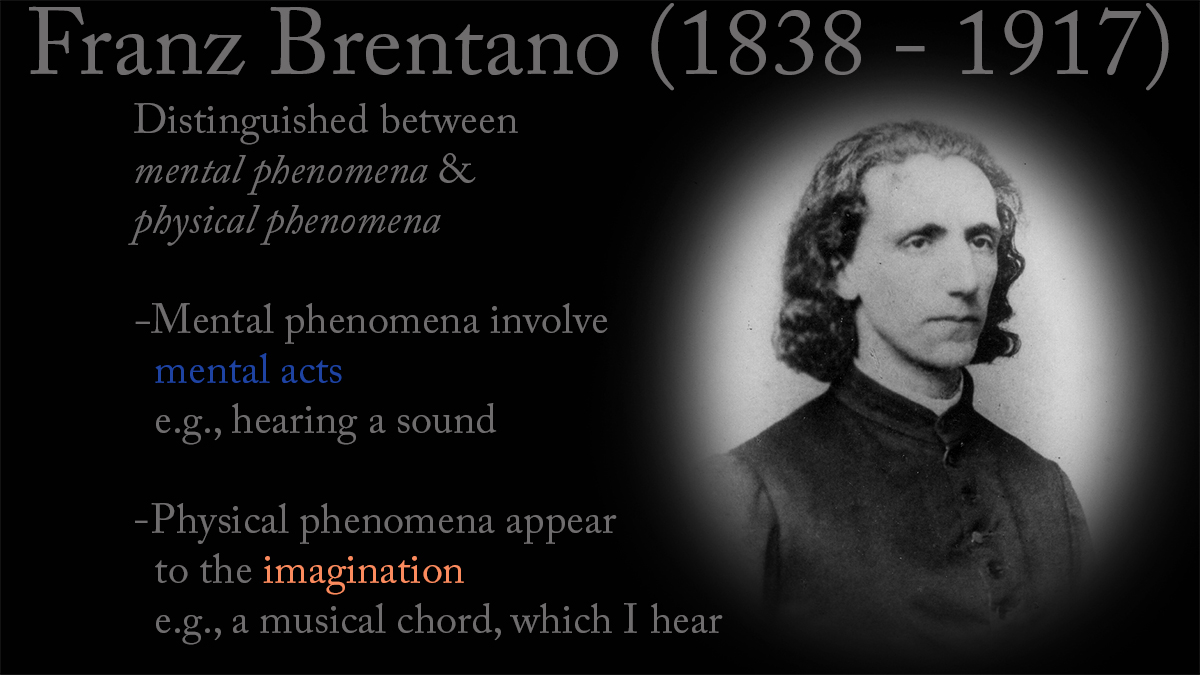

In 1881, he received his doctorate in medicine. While at university, Freud was part of an investigation of the precise structure of the testes of eels, which involved his dissecting over 400 eels. Later, he moved on to physiology and neuroanatomy and conducted experiments examining the spinal cord of fish. While at Vienna, Freud also took courses with Franz Brentano, which formed his only formal introduction to 19th century psychology.

After waiting for Freud for about 4 years, his fiancée, Martha Bernays, a jewish girl from a business family and the grand-daughter of a famous Rabbi in Hamburg, married him. While she did not show great interest in Freud’s intellectual pursuits, her younger sister Minna became a very close intellectual partner of Freud. Carl Jung one of Freud’s intellectual ally who would become one of his firmest critic would even later say that he learned from Minna that Freud was in love with her and their relationship was very “intimate” – although we have no factual confirmation of such. She was so close to the young couple, that she moved in with them in the 1890s to set up was has been “jokingly” called a “ménage a trois”. As for Martha, she was also a charmer, intelligent, well-educated and fond of reading who as a married woman ran her household efficiently and was almost obsessive about punctuality and dirt. Firm but loving with her children, French analyst René Laforgue said that she spread an atmosphere of peaceful joie de vivre through the household. Shortly after Freud’s wedding, he recognised that a scientific career would not provide adequate income, since anti-Jewish sentiments were strong around Europe and this worked against Jewish advancement in academia even if Freud himself was not a practising Jew or had any religious sentiments. So Freud reluctantly decided to begin a private practice. Although the young couple were very poor in the early years of their marriage, Freud was able to support his wife and his growing family, which eventually included 6 children. The early years in private practice were very difficult, requiring long hours for a meagre financial reward that basically did not challenge him. Freud was also an atheist and did not want psychoanalysis to be seen as a purely Jewish endeavour, and his close network although were mainly Jewish later slowly grew to incorporate European intellectuals where some of the most significant would disagree with some of his assumptions and leave his circle after keeping only a few of his fundamental concepts about the theory of mental life.

During his hospital training, Freud had worked with patients with anatomical and organic problems of the nervous system. Shortly after starting private practice, he became friendly with Josef Breuer (1842 – 1925), a general practitioner who had acquired some local fame for his respiration studies. This friendship provided needed stimulation for Freud, and they began to collaborate on several patients with nervous disorders, most notably the famous case of Anna O., an intelligent young woman with severe, diffuse hysterical symptoms. In using hypnosis to treat Anna O., Breuer noticed that some specific experiences emerged under hypnosis that the patient could not recall while conscious. Her symptoms seemed to be relieved after talking about these experiences under hypnosis. Breuer treated Anna O. daily for over a year, and became convinced that the “talking cure”, or “catharsis”, involving discussion of unpleasant and repulsive memories revealed under hypnosis, was an effective method in alleviating her symptoms. Unfortunately, Breuer’s wife became jealous of the relationship; that would later be called “positive transference of emotional feelings to the therapist”. This would later be explained as patients falling in love with the new object [in this case, the psychoanalyst] at which they redirect feelings and desires retained in childhood at characteristic stages of therapy. This looked suspicious to Breuer’s wife. As a result, Breuer terminated his treatment of Anna O. Freud was also very professional with his clients and never had any mistresses or took advantage of his female patients. In opposition to positive transference, the psychoanalyst may also face negative transference in treatment with patients, which refers to aggressive affects, definitions that would also be taken by Lacan who criticised Ego-psychology for defining transference simply in terms of a range of affects. Lacan explained that transference does not refer to any mysterious property of affect in patients, and even when it reveals itself under the appearance of emotion, it only acquires meaning by the virtue of that very precise dialectical moment in which it is produced; that is to say that transference with patients often manifests itself in the form of strong affects, such as love and hate, but it does not consist of such emotions, it is part of the structure of the intersubjective relationship of patients in praxis with the psychoanalyst at that very moment. Lacan saw the Symbolic aspect of transference, which is repetition, as a feature that helped the treatment of patients since it reveals the meaningful signifiers of the personal history of Subjects, while the Imaginary aspect (love and hate) during treatment acts as resistance to psychoanalytic praxis.

Jean-Martin Charcot (1825 – 1893) / Charcot first began studying hysteria after creating a special ward for non-insane females with “hystero-epilepsy”. He discovered two distinct forms of hysteria among these women: minor hysteria and major hysteria. His interest in hysteria and hypnotism “developed at a time when the general public was fascinated in ‘animal magnetism’ and ‘mesmerization'”, which was later revealed to be a method of inducing hypnosis.

Charcot argued vehemently against the widespread medical and popular prejudice that hysteria was rarely found in men, presenting several cases of traumatic male hysteria. He taught that due to this prejudice these “cases often went unrecognised, even by distinguished doctors” and could occur in such models of masculinity as railway engineers or soldiers. Charcot’s analysis, in particular his view of hysteria as an organic condition which could be caused by trauma, paved the way for understanding neurological symptoms arising from industrial-accident or war-related traumas.

In 1885, Freud received a modest grant that allowed him to go to Paris to study with Jean-Martin Charcot for 4 and half months. During that time he not only observed Charcot’s method of hypnosis [which he never managed to master as Charcot did] but also attended his lectures, learning about the master’s views on the importance of unresolved sexual problems in the underlying causality of hysteria. When Freud returned to Vienna, he gave a report of his work with Charcot to the medical society, but its cold reception left him with resentment that affected his future interactions with the entrenched medical establishment and its rigid and reductionist methods at understanding and solving the problems of the mind.

Freud continued his work with Breuer on hypnosis and catharsis, but gradually abandoned the former in favour of the latter, being not very gifted with hypnotic techniques, but also for 3 major reasons regarding its effectiveness as a treatment with general applicability. First, not everyone can be hypnotised; hence its usefulness is limited to a select group. Second, some patients refuse to believe what they revealed under hypnosis, prompting Freud to conclude that the patient must be aware during the step-by-step process of discovering memories hidden from their accessible consciousness. Third, when one set of symptoms were alleviated under hypnotic suggestibility, new symptoms often emerged. Freud and Breuer were moving in separate directions, and Freud’s increasing emphasis on the primacy of sexuality as the key to psychoneurosis contributed to their break. Nevertheless, in 1895 they published Studies on Hysteria, often cited as the first work of the psychoanalytic movement, although it sold only 626 copies during the following 13 years – perhaps due to the lack of sophistication and interest in the workings of the mind at that particular point in history, or the level of the academic discussions that may not have been adequate for the intellect of the average mind at the time.

Freud’s preferred method of treatment, catharsis, involves engaging with patients and encouraging them to speak of anything that comes [occupies] their mind, regardless of how discomforting or embarrassing it might be. This “free association” took place in a relaxed atmosphere, usually on the classic psychologist couch in a reclined position to promote comfort. The main reason behind the logic of catharsis and free association is that – like hypnosis – it would allow hidden thoughts and memories to manifest in consciousness. However, in contrast, to the method of hypnosis, the patient would be aware of these emerging recollections. Another ongoing process during free association is “transference”, which involves emotionally laden experiences that allow the patient to relieve earlier, repressed episodes. Since the psychoanalyst is often part of the transference process [as mentioned earlier where the repressed emotions are often redirected onto] and is often the object of his patients’ emotions, Freud recognised transference as a powerful tool to assist patients in resolving sources of anxiety. Lacan proposed that it is important to also understand that although the existence of transference plays an important part for psychoanalytic treatment, it is not enough by itself, it is also necessary for the psychoanalyst to deal with the transference in a unique way, this is what differentiates true psychoanalysis from suggestion because the psychoanalyst refuses to use the power given to him by the transference. Lacan believed like any other interpretation, the analyst must use all his “art” in deciding if and when to interpret the transference and must above all avoid gearing his interpretations exclusively to interpreting the transference; the analyst must know exactly what he wants to achieve by such an interpretation and it should not rectify his patients’ relationship to the vague concept of “reality”, but instead maintain analytic dialogue. Transference is the displacement of affect from one idea to another and Freud viewed it as a positive factor that helps the progression of treatment since it provides a way for patients’ history to be faced in the immediacy of the present relationship with the analyst; the way patients relate to the analyst is revealing as they inevitably repeat earlier relationships with other meaningful others [especially those with the parents or parental figures] – this logic is underlined in the theory of attachment of John Bowlby. Jacques Lacan later remarked that if transference with most patients often manifests itself under the appearance of love, it is first and foremost the love of knowledge (savoir) that is concerned. Transference is the attribution of knowledge to the Other, the assumption that the Other is a Subject who “knows” [Le Sujet supposé savoir], and as soon as that “knowing” Subject appears, we have transference. Lacan used Plato’s symposium to illustrate the relationship between analysands (i.e. patients) and the analyst; Alcibiades compared Socrates to a plain box which enclosed a precious object, just as Alcibiades attributes a hidden treasure to Socrates so patients see the object of their desire in the analyst (i.e. “objet petit a” in Lacanian terms). The psychoanalyst must sometimes situate himself/herself as the substitute for objet petit a in the course of psychoanalytic praxis. Lacan also identifies the compulsion to repeat with the symbolic nature of transference, the symbolic determinants of all Subjects, and this helps the progression of treatment by revealing the meaningful signifiers of Subjects’ personal history; he also locates the essence of transference in the Symbolic and not in the Imaginary, although it clearly has powerful imaginary effects.

In 1897, Freud began a self-analysis of his dreams, which evolved into another technique important to the psychoanalytic movement. In the analysis of dreams, Freud distinguish between the manifest content [the actual depiction of the dreams] and the latent content, which represented the symbolic world of the patient. In 1900, he published his major work, The Interpretation of Dreams. Although it sold only 600 copies in eight years, it later went through eight editions in his lifetime. In 1901, he published The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, the book in which his theory began to take shape. Freud argued that the psychology of all people, not only those with neurotic symptoms, could be understood in terms of the unconscious forces in need of resolution.

When his reputation as a pioneer in psychiatry started to grow due to his prolific writings, Freud attracted admiring followers, among them was the notable Carl Jung. In 1909, G. Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, invited him to the United States to give a lecture series as part of that institution’s 20th anniversary. The lectures were published in the American Journal of Psychology and later in book form, serving as an appropriate introduction to psychoanalytic thought for American audiences.

As psychoanalysis was perceived as radical by the medical establishment, early believers form their own associations and found the journals to disseminate their competing views. However, Freud’s demand for strict loyalty to his interpretation of psychoanalysis led to some discord within the movement [perhaps for the betterment of the field itself as many branches kept the fundamental concept of unconscious (Id), pre-conscious (SuperEgo), and conscious (Ego) but fused other theoretical and scientific perspectives to explain and treat a range of mental illnesses]. Carl Jung broke away in 1914, so that by the following year, three rival groups existed within the psychoanalysic movement. Nevertheless, Freud’s views continued to evolve. Impressed by the devastation and tragedy of World War I, Freud came to view aggression, along with sexuality, as a primal instinctual motivation. During the 1920s Freud expanded psychoanalysis from a method of treatment for mentally ill or emotionally disturbed persons to a systematic framework for all human motivation and personality.

In 1923, Freud developed cancer of the jaw and experienced almost constant pain for the remaining 16 years of his life. He underwent 33 operations and had to wear a prosthetic device. Throughout this ordeal however, he continued to write and see patients, although he shunned public appearances. With the rise of Hitler and the anti-Jewish sentiments that arose with his campaigns with the National Socialists, Freud’s works were unfortunately singled out as they were not seen as a scientific endeavour but rather as a Jewish science, and his books were burned throughout Germany. However, Freud resisted fleeing from Vienna. When Germany and Austria were politically united in 1938, the Gestapo began harassing Freud and his family. President Roosevelt indirectly relayed to the German government that Freud is an intellectual who must be protected. Nevertheless, in March 1938 some thugs invaded Freud’s home. Finally, through the efforts of friends, Freud was granted special permission, but only after promising to send for his unsold books in Swiss storage so that they could be destroyed. After he signed a statement saying that he had received good treatment from the police, the German government allowed him to leave for England, where he died shortly after, on September 23, 1939.

An overview of the Psychoanalytic System based on Freud’s Research

Before our in-depth examination of psychoanalytic theory, it is important to recognise that the theory has an unusually broad focus. Psychoanalysis contains a theory of personality, but it also offers theoretical tools for understanding culture, society, art and literature. It is also a clinical theory that aspires to explain the nature and origins of mental disorders, and that is associated with an approach to their treatment. To give some more sense to Freud’s breadth, consider that he wrote on topics as diverse as the meaning of dreams and jokes, the origins of religion, Shakespeare’s plays, the psychology of groups, homosexuality, the causes of phobias and obsessions, and much more besides. Even as a theory of personality, psychoanalysis is primarily an account of the processes and mechanisms of the mind, rather than an account of individual differences.

In addition to its breadth of focus, the psychoanalytic theory has many distinct components that have also been modified and explored by a range of skilled psychoanalysts, making it hard to integrate into a single unitary model of the mind since they are inter-connected in complex ways.

Freud’s views evolved continually throughout his long career in the collective result of his extensive writings as an elaborate system of personality development. Personality was described in terms of an energy system that seeks an equilibrium of forces. This homeostatic model of human personality was determined by the constant attempt to identify appropriate ways to discharge instinctual energies, which originate in the depths of the unconscious. The structure of personality, according to the psychoanalytic model consists of a dynamic interchange of activities energised by forces that are present in the person at birth. This homeostatic model was consistent with the prevailing views of 19th-century science, which saw the mechanical relations of physical events studied by physics as the term of scientific inquiry. Freud’s model for psychoanalysis translated physical stimuli to psychic energies or forces and retained an essentially mechanical description of how such forces interact.

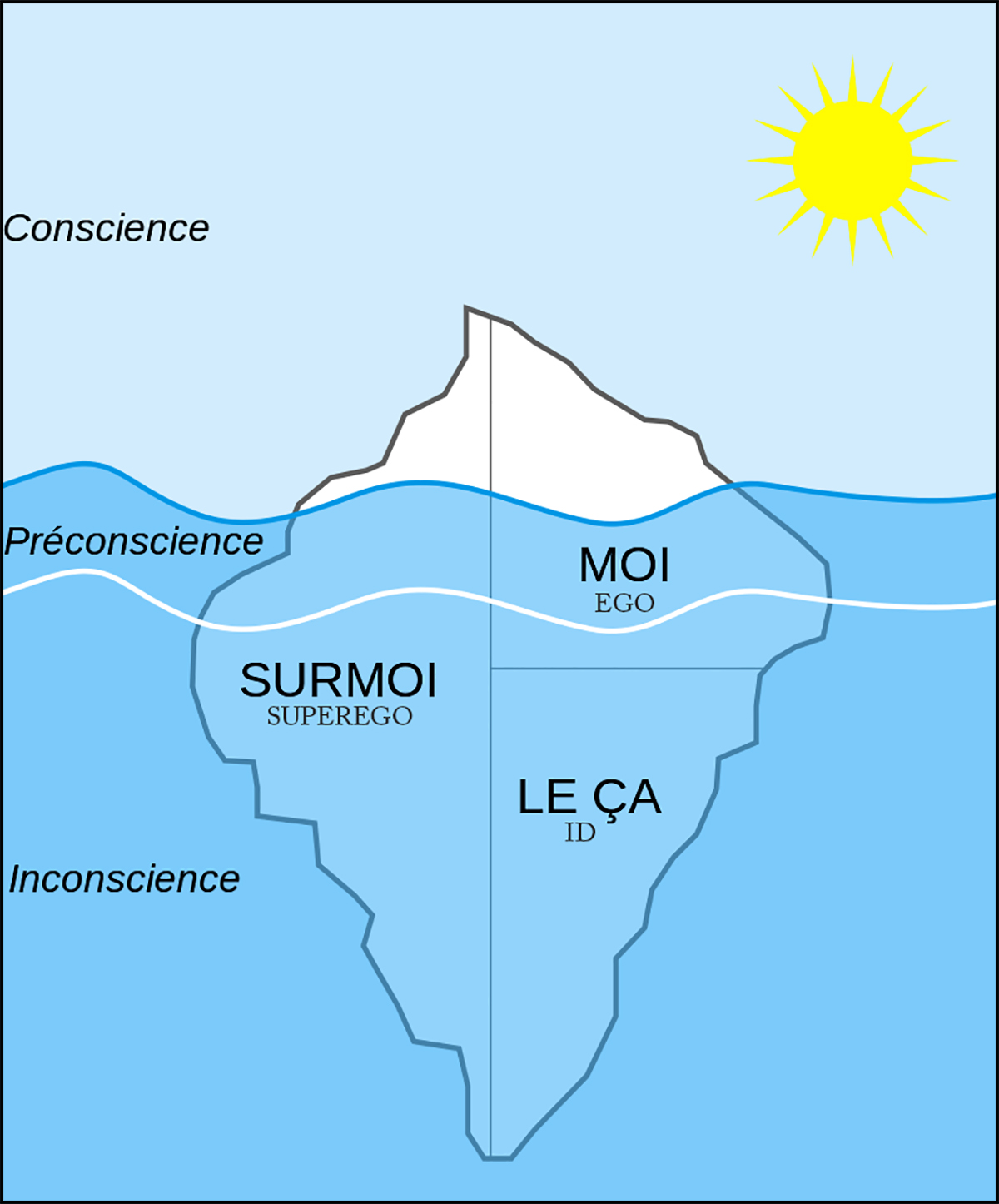

As the writings on the dpurb.com website are the foundations for the Organic Theory of Psychological Construction, we are going to be focused not on the later structural model which repositioned the Unconscious, Conscious and Pre-Conscious across the Id, Ego and SuperEgo, but with the first topographic model (1900 – 1905) adopted by both Carl Jung and Jacques Lacan. This model, has been more influential and is more flexible in accommodating competing view points about the structure of mental life across individuals.

The topographic model refers to the levels or layers of mental life. Freud proposed that mental content – ideas, wishes, emotions, impulses, memories, and so on – can be located at one of the three levels: the Conscious (later known as the Ego), the Preconscious (SuperEgo) and the Unconscious (Id), . It is important however, to understand that Freud use these terms to describe degrees of awareness and unawareness, but also to refer to distinct mental systems with their own distinct laws of operation. Unconscious cognition is categorically different from Conscious cognition, in addition to operating on mental content that exists beneath awareness. To convey this point, the three levels of the topographic model was referred to as the ‘systems’ Cs., Pcs., and Ucs.

The Topographic Model

The Conscious (which would later be known as Ego with a partial unconscious side, and also “Le Moi” in Lacanian Theory)

Consciousness is merely the proverbial ‘tip of the iceberg’ of mental activity. The contents of the Conscious are simply the small fraction of things that the person is currently paying attention to: objects perceived, events recalled, the stream of thought that we engage in as a running commentary on everyday life. [This is the main focus of most other branches of Psychology such as Biological Psychology and Cognitive Psychology]

The Preconscious (which would later be known as the Super-Ego, le “Grand Autre” in Lacanian Theory)

Of course, not all of all mental life happens under the spotlight of awareness and attention. There are many things to which we could readily pay attention to but do not, such as ideas or plans we have set aside or memories of what we were doing last week or yesterday. Without any great effort these things or events, which in the present are out of consciousness, can be made conscious. Those form the domain of the Preconscious.

The boundary between the Conscious (Ego) and the Preconscious (Super-Ego) is a permeable one. Thoughts, memories and perceptions can cross without great difficulty according to the momentary needs and intentions of the individual. They also share a common mode of cognition, which in psychoanalysis is known as the ‘secondary process’. Secondary process cognition is the sort of everyday, more or less rational thinking than generally obeys the laws of logic.

The Unconscious (which would later be known as the Id, L’inconscient or the “Ça” in Lacanian Theory)

The Unconscious (Id) is perhaps one of the most celebrated theoretical concepts in psychoanalysis’ legacy. However, Freud did not invent or discover the unconscious as is sometimes claimed – versions of the unconscious had been floating around intellectual circles for some time – but Freud gave it a much deeper theoretical analysis than anyone before him. Freud distinguished between mental contents and processes that are descriptively unconscious and those that are dynamically unconscious. The descriptively unconscious simply exists outside consciousness as a matter of fact, and therefore include Preconscious material that can become conscious if it is attended to. Freud’s crucial contribution was to argue that some thoughts, memories, wishes and mental processes are not only descriptively unconscious, but also cannot be made conscious because of a countervailing force keeps them out of awareness. In short, mental life that is dynamically unconscious is a subset of what is descriptively unconscious, one whose entry to consciousness is actively thwarted. The Freudian unconscious corresponds to the dynamic unconscious in this sense.

Freud held that the Unconscious contains a large but unacknowledged proportion of mental life that operates according to its own psychological laws. The barrier between the Unconscious (Id) and the Preconscious (SuperEgo) is much more fortified and difficult to penetrate than the border between the Preconscious (Super-Ego) and Conscious (Ego). In addition, it is policed by a mental function that Freud likened to a “censor”. The censor’s role is to determine whether the contents of the Unconscious would be threatening / objectionable or socially unacceptable to the person if they became conscious. If the censor judges them to be dangerous in this type, the person will experience anxiety without knowing what caused it. In this case, these thoughts become wishes and so on, and will be normally be repelled back into the Unconscious, in a process referred to as “Repression” [it is fundamental and very important to understand that Repression is something else than a conscious judgement which rejects and chooses]. Unconscious material, by Freud’s account, has an intrinsic force propelling it to become conscious. Consequently, repression required an active opposing force to resist it, just as effort is required to prevent a surf board made of white foam to rise to the surface when it is submerged in the ocean. Under the constant pressure of Unconscious material bubbling towards the Preconscious, the censor cannot possibly bar entry to everything. Instead, it allows some Unconscious material to cross over the barrier after it has been transformed or disguised in some way so as to be less objectionable and more socially acceptable. This crossing might take the form of a relatively harmless impulsive behaviour, or in the form of private fantasy, the telling of a joke, or in a slip of the tongue, where the person says something ‘unintentionally’ that reveals to the trained eye and mind the repressed concerns and wishes [such as that of a psychoanalyst – as Jacques Lacan proposed: repression can take the form of a metaphor and the skilled psychoanalyst must be able to decipher a chain of clues with a great deal of verbal dexterity where crossword puzzles may help in training. Lacan also viewed the Grand Autre (Preconscious/Superego) as the discourse of the Unconscious]. Psychoanalysis focuses on how phenomena such as these can be interpreted, the process that involves uncovering the unconscious material that is concealed within their “disguises” [i.e. forms].

To Freud, dreams represent a particularly good example of the disguised expression of the Unconscious wishes. They offered, he wrote, “the royal road to the Unconscious”. One reason for this is that during sleep, the sensor relaxes and allows more repressed Unconscious material to cross the barrier. This material, transformed into a less threatening form by a process referred to as the “dream-work”, then takes the shape of a train of images in the peculiar form of consciousness that we call dreaming. It is believed, that each dream has a “latent content” of Unconscious wishes that is transformed into the “manifest content” (or dream narrative) of the experienced dream. In psychoanalytic praxis with patients, the interpretations of dreams takes the same road, but in reverse, in order to decode the transformations rendered by the dream work so as to bring out the latent content based on the manifest content. Freud described the “latent contents” as made up of “latent thoughts“, a term that was always used in the plural form and never precisely described, but the context of its usage seems to suggest that it connoted representations, affects, wishes and conflictual patterns that are all profoundly marked by infantilism and fantasy [e.g. having super powers and flying while dressed in a nylon costume]. Latent thoughts also contain whatever supplies the dream’s “raw material”: the days residues, somatic sensations, and excitations that directly impact instinctual impulses. The transformation carried out by the dream work has to allow the Unconscious wishes during the wake state to be fulfilled during the dream while concealing the elements of threat they contain. If the latent content is not concealed sufficiently through the “dream-work” process, the sleeper will register the threat and be awoken [sometimes in shock and sweat], and to avoid this shock the dream-work may alter the identities of the people represented in a wish, for example, if an individual has an Unconscious wish to harm a loved one, the dream work might produce a dream in which the individual instead harms someone else or in which the loved one is harmed by another person, neutralised in this way, the unconscious wishes find conscious expression in the dream. Freud explained that “latent thoughts” were generally preconscious; they are used by the dream work because they are a relay point and medium for unconscious cathexes [i.e. objects (or ideas) that have a quantity of psychical energy attached to them; to say that an object or idea is “libidinally” cathected means that it is charged with sexual energy deriving from sources internal to a patient’s psyche; the Id (Unconscious) or the instinctual pole of personality is said to be be the source all types of cathexes]. Dreams also showcase the distinct form of thinking that operates in the Unconscious: “Primary process” thinking, which unlike the secondary process than governs the Conscious (Ego) and Preconscious (Super-Ego), shows no respect for the laws of logic and rationality. In primary process thinking, something can stand for something else, including its opposite, and can even represent two distinct things at once. Contradictory thoughts can coexist and there is no orderly sense of the passage of time or of causation. Basically, primary process thinking captures the magical, chaotic qualities of many dreams, the mysterious images that seems somehow significant, the fractured storylines, the impossible and disconnected events. To Freud, dreams are not simply night-time curiosities, but reveal how the greater part of our mental life proceeds beneath the shallows of conscience.

Foundations of the later “Structural” model: concepts to consider and synthesise with the Topographic Model

We are now going to have a look at the later version of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory where the Unconscious [this time referred to as the Id] is still the fundamental concept, however decades later in 1923, another 3-way dissection of the mind was proposed. This time Freud called it the Psychic Apparatus and the 3-way dissection of the mind was defined in terms of distinct mental functions instead of levels of awareness and their associated processes.

The Structural Model of the Psychic apparatus

In original German, the terms Es (Id), das Ich (Ego) and Über-ich (Super-Ego) were used. As we take a look at these structures, it is important to remember that they were not proposed as real underlying entities, but rather as a sort of conceptual shorthand for talking about different kinds of mental processes. Our aim here is to synthesise the logical concepts of the Structural Model with the earlier Topographic Model of the Unconscious (Id), the Preconscious (Super-Ego) and the Conscious (Ego), however although it is convenient to talk about the Id, Super-Ego and Ego “doing” such-and-such or being “in charge of” so-and so, it is important to remember that they were not intended to refer to distinct sub-personalities within the individual.

The Id (Unconscious, das Es / Inconscient / Le Ça)

The Id [completely/dynamically unconscious] represents the part of the personality that is closely linked to the instinctual drives that are the fundamental sources of motivation in Freudian theory. According to Freud, these drives are chiefly sexual and aggressive in nature. On one hand we have the “life instincts” concerned with preserving life and binding together new “vital unities”, the foremost expression of this concern being loving sexual union. Opposed to these life instincts, on the other side, we have the set of “death instincts”, whose corresponding concern is with breaking down life and destroying connections, its goal is a state of entropy or nirvana, where there is a complete absence of any form of tension [motivation] – the most obvious form of these instincts were aggressiveness expressed inward towards the self or outward towards others. Freud proposed that these instinctual biological drives were powered by a reservoir of instinctual “psychic energy” grounded in basic biological processes; the sexual form of this energy was referred to as libido. Although the unconscious Id is a biological underpinning, its contents are manifested in psychological phenomena such as wishes, ideas, intentions, and impulses. These phenomena are therefore sometimes described as “instinct- derivatives”. Some of these phenomena are innate, whereas others have been consigned to the Id by the process of repression. All of the Id’s contents, however are unconscious. Freud proposed that the Id operated according to what he called the “pleasure principle” which states that the Id’s urges strive to obtain pleasure and avoid “unpleasure” without delay. Unpleasure results from increased accumulated excitation and pleasure results from its reduction. Lacan used the term “Jouissance” to describe an excessive quantity of excitation that has the potential to take the Subject to that extreme point where the erotic borders upon death and where subjectivity risks extinction; the “pleasure principle” tries to prevent such savage scenarios [To Lacan, the pleasure principle is a commandment — which can be phrased — “Enjoy as little as possible.” The pleasure principle leads the subject from signifier to signifier, by generating as many signifiers as are required to maintain at as low a level as possible the tension that regulates the whole functioning of the psychic apparatus]. One of Lacan’s contribution to the debate on feminity advances the concept of a specifically feminine jouissance which goes beyond the phallus: a jouissance of the order of the infinite like mystical ecstacy where women may experience this without being conscious about it. Therefore the pleasure principle serves to reduce tension and to return the psyche to a state of equilibrium or constancy. Pleasure, in Freud’s understanding, represented a discharge of libido or instinctual energy which is accompanied by a release of tension. The Id is not in contact with the rules or structures of individuals’ environment [i.e. the Symbolic rules of civilised society], but rather relates to the other structures of personality, the Ego & the Superego [conscience] that in turn must mediate between the Id’s raw instincts and the external world; immune from reality and social convention, the Id which is guided by the pleasure principle, seeks to gratify instinctual libidinal needs [that are simply biological] either directly through a sexual experience, or indirectly by dreaming or fantasizing. The latter, indirect gratification was called the primary process [governed by the pleasure principle] and has its own “rules” [e.g. allowing contradictions in logic] that differ from Ego functions and conscious thought. The exact object of direct gratification in the pleasure principle is assumed to be determined by the psychosexual stage of the individual’s development [as explained in 3rd part of the essay on The 3 Major Theories of Development], however the legitimacy and precision of this theory has been questioned and revised over the years and it gave way to the more empirical Theory of Attachment of John Bowlby. In short, the Id strives to satisfy its drives enabling immediate, pleasurable release of instinctual energy. It is the most primitive and least accessible structure of personality. As originally described by Freud, the Id is psychic energy of an irrational nature, and in the form of libido, it can manifest itself and be of a sexual character that is incestuous, uninhibited, savage, irrational and boundless, which instinctually determines unconscious processes. In psychoanalysis, this natural, wild and irrational urge is assumed to be present in all human beings. Elisabeth Roudinesco pointed out that Freud had distinguished that in humans it is the desire for incest and not the horror of it, that eventually leads individuals to forbid themselves from expressing it while also rejecting it; that is to say that in healthy, civilised and psychologically stable individuals with a well developed conscience [i.e. Superego] there is a respect for the symbolic laws that govern human relationships ethically [Lacan proposed that these symbolic structures are primarily governed by language] and which involve abiding by a structure that respects shared social values that sustain a functional human civilisation, i.e. the passage from raw and savage nature [Id] to civilised culture [Super Ego]. Many modern psychoanalysts believe that repression, masturbation and sublimation are inescapable in order to manage the raw and wild instincts of the Id and to channel them in more productive endeavours that are in the best interests of individuals and civilised society.

The Ego (Conscious & partially unconscious, Ich / Le Moi)

The Ego, is a mental function and complicates the picture of immediate gratification that the Id strives for. The Ego, a “psychic agency”, arises over the course of development as the child learns that it is often necessary and desirable to delay gratification. The bottle or breast does not always appear the instant that hunger is first experienced, and sometimes it is better to resist the urge to urinate at the bladder’s first bidding if one is to avoid the unpleasure of wet pants, embarrassment, and a parent’s howls of dismay. The Ego, often called the “executive” of personality because of its role in channeling Id [unconscious] energies into socially acceptable outlets [ego is believed to start developing between the ages of 1 and 2 as the child confronts the environment]. The Ego crystallises out this emerging capacity for delay, and in time becomes a restraint on the Id’s impatient striving for discharge. However, it cannot be an inflexible restraint. Its task is not to delay the fulfilment of wishes and impulses endlessly, but to determine when and how it would be most sensible or prudent to do so given the demands of the external environment at a particular time. It operates, that is, on the “Reality principle”, which simply requires that the Ego regulate the person’s behaviour in accordance with external conditions [at a given time or place according to certain rules or laws or conventions, and of course this changes as society redefines “reality” in terms of what it acceptable and not]. Freud emphasized that the Ego is not the dominant force in the personality [unlike Ego psychologists in the US state], although he believed it should strive to be. A famous statement of Freud regarding the goal of Psychoanalytic treatment is “Where Id was, there Ego shall be”. By his account, the Ego not only emerges out of the Id in the course of development – beforehand, the infant is pure Id [instinctive and irrational] – but it also derives all of its energy from the Id. Freud had a gift for metaphor, and he likened the Ego’s relation to the Id as a rider’s relation to a wilful horse. The horse [Id] supplies all of the pair’s force, but the rider [Ego] may be able to channel it in a particular direction. Fortunately, this “rider” [Ego] has a repertoire of skills at its disposal. Freud proposed that the Ego could employ a variety of “defence mechanism” in the service of the reality principle. These mechanisms come in a diverse range, and all represent operations that the Ego performs to deal with the threats to the rational expression of the person’s desires, whether from the Super-Ego or the external environment. These Ego defence mechanisms are common processes in everyday mental life, and many of them are carried out by the Ego unconsciously, showing that there is an unconscious part in the Ego. The Ego being governed by the reality principle, is aware of environmental demands and adjusts behaviour so that the instinctual pressures of the id are satisfied in acceptable ways, and the attainment of specific objects to reduce libidinal energy in socially appropriate ways was called the “secondary process” [the “primary process” being the Unconscious (Id)]. Some of the most well known defence mechanisms are denial, isolation of affect, projection, reaction formation, repression and sublimation.

The Super-Ego (Conscious & partially unconscious, Über-ich / Le Surmoi / L’Autre / Le Grand-Autre)

The differentiation of the structures of personality, called the Super-Ego, is believed to start appearing by the age of 5. In contrast to the Id and Ego, which are internal developments of personality, the Super-Ego is an external imposition. That is the Super-Ego is the incorporation of moral standards perceived by the Ego from some agent of authority in the environment, usually an assimilation of the parents’ views as the child develops – both positive and negative aspects of these standards. The Super-Ego’s emergence complicates the task of the Ego in regulating the expression of the Id’s impulses in response to demands and opportunities of the external environment. The Super-Ego represents an early form of conscience, an internalised set of moral values, standards, and ideals. These moral precepts are not the sort of flexible, evolving, reasoned, and discussable rules of conduct that we tend to imagine when we think of adult morality, however, instead they tend to be relatively harsh, absolute and punishing; adult morality as refracted through the immature and fearful mind of a child. The Super-Ego therefore represents the shrill voice of societal rules and restrictions, a voice that condemns and forbids many of the sexual and destructive wishes, impulses and thoughts that emerge from the Id. The positive moral code is the Ego ideal, i.e. a representation of behaviour for the individual to emulate. The conscience embodies the negative aspect of the Super-Ego, and determines which activities are to be taboo. Conduct that violates the dictates of the conscience produces “guilt” in healthy individuals. Hence, the Super-Ego and the Id are in direct conflict, leaving the Ego to mediate. The Ego now becomes the servant of three masters: the Id, the Super-Ego and the External Environment [Societal Rules]. It is now not enough to reconcile what is desired with what is possible under the circumstances because now the Ego also needs to take into consideration what is socially prohibited and impermissible. Instinctual drives must still be satisfied; which is a constant, however the Ego now attempts to satisfy them in a way that is flexibly “realistic” – that is, in the person’s best interests under current conditions – but also “socially” permitted. These prohibitions are often very unreasonable and inflexible, rejecting any expression of the drive with an unconditional “NO”, either because the moral structures of a particular “culture” are intrinsically rigid, atavistic or unsophisticated, or because the individual’s internalisation of these structures is simply black-and-white, without any grey area to compromise for an adequate and acceptable form of expression of the drive. Thus, the Super-Ego imposes a pattern of conduct that results in some degree of self-control through an internalised system of rewards and punishments.

Given the demands that it faces, the Ego can either find a way to express the Id’s desires successfully, or its attempts to arbitrate can fail. In this case, psychological trouble is likely to follow. If the Id wins the struggle, and the desire finds expression in a more-or-less unaltered and primitive form, the person may experience guilt or shame: the Super-Ego’s sign that it has been violated, and may also have to pay the price of a short-sighted, impulsive action. If on the other hand, the Super-Ego wins the struggle and dominates a person excessively, that individual may become overly rigid, rule-bound, uncreative, unquestioning, anxious and joyless. The forbidden desires may well go “underground” and manifest themselves in symptoms such as anxieties, compulsions or in occasional “out-of-character” impulsive behaviour or emotion.

Intrapsychic Conflict: the Roots of Personality

The major motivational constructs of Freud’s theory of personality was derived from instincts, defined as biological forces that release mental energy. Hence, from the account of the Unconscious (Id), the Conscious [and partly unconscious, Ego) and the Preconscious (Super-Ego), it implies that conflict within the mind’s opposing forces is inevitable, because the demands of society – or “civilisation” – are generally opposed to the natural instincts and drives of human beings. Indeed, intrapsychic conflict is one of the fundamental and defining concepts of psychoanalysis. Conflict within the mind is at the root of personality structure, mental disorder, and most psychological phenomena [e.g. artistic expressions of various forms]. The goal of personality is to reduce the energy drive through some activity acceptable to the constraints of the Super-Ego [Preconscious].

Freud classed inborn instincts to life (eros) and death (thanatos) drives. Life instincts involve self-preservation and include hunger, sex and thirst. The libido is that specific form of energy through which life instincts arise in the Id. The death instinct (Thanatos) may be directed either inwards, as in suicide or masochism, or outwards, as in hate and aggression. The notion that personality equilibrium must be maintained by discharging energy in acceptable ways, leads to anxiety which plays a central role. Essentially the view is that anxiety is a diffuse fear in anticipation of unmet desires and future evils. Given the primitive character of Unconscious (Id) instincts, it is unlikely that primary goals are ever an acceptable means of drive reduction; rather they are apt to give rise to continual anxiety in personality. Freud described three general forms of anxiety.

(i) Reality (or Objective) Anxiety

(ii) Neurotic Anxiety

(iii) Moral Anxiety

Reality or objective anxiety, is a fear of the real environmental danger [e.g. heights, depth, fire, etc] with an obvious cause; such fear is appropriate as it has survival value for the organism. Neurotic anxiety comes about from the fear of potential punishment inherent in the goal of instinctual gratification. It is a fear of punishment for expressing impulsive desires. Finally, moral anxiety is the fear of the conscience through guilt or shame in healthy individuals. In order to cope with anxiety, the Ego develops defence mechanisms, which are elaborate, largely unconscious processes that allow a person to avoid unpleasantness and anxiety-provoking events. For example, an individual may avoid facing anxiety by self-denial, conversion [whereby the anxiety caused by repressed impulses and feelings are ‘converted’ into a physical complaint such as a cough or feelings of paralysis], or projection, or may repress thoughts that are a source of anxiety into the unconscious. Many defence mechanisms are described in the psychoanalytic literature, which generally agrees that although defence mechanisms are typical ways of handling anxiety and maintaining a sense of psychological stability, they must be recognised and controlled by the individual himself/herself for psychological health. Lacan sees “defence” as being on the side of the Subject [being stable symbolic structures of subjectivity].

Denial |

Refusing to acknowledge that some unpleasant or threatening event has occurred; common in grief reactions |

Isolation of Affect |

Mentally severing an idea from its threatening emotional associations so that it can be held without experiencing its unpleasantness; common in obsessional people |

Projection |

Disavowing one’s impulses thoughts and attributing them to another person; common in paranoia |

Reaction formation |

Unconsciously developing wishes or thoughts that are opposite to those that one finds undesirable in oneself; common in people with a rigid moral code |

Repression |

Repression is one of the most basic concepts in psychoanalysis. It involves repelling threatening thoughts from consciousness, to confine them in the unconscious. Freud distinguished between: (i) primal repression [a “mythical” forgetting of something that was never conscious, an ordinary “psychical act” by which the unconscious is first constituted. Lacan saw this as a structural feature of language, its necessary incompleteness, the impossibility of ever formulating the “truth about truth” (because human language is limited and can never capture and completely express the Unconscious), the symbolic signifying chain of the unconscious where linguistic discourse originates]; and (ii) secondary repression [concrete acts of repression whereby some idea or perception that was once conscious is expelled from the conscious (E.g. motivated forgetting; common in post-traumatic reactions). Lacan saw secondary repression as a specific psychical act by which a signifier is elided from the signifying chain, it is structured like a metaphor and involves the return of the repressed, since repression does not destroy the ideas or memories but merely confines them to the unconscious, the repressed material is liable to return in distorted form, in symptoms, dreams, slips of the tongue, etc. To Lacan, it is always the signifier that is repressed, never the signified, which corresponds to Freud’s view that what is repressed is not the “affect” (which can only be displaced or transformed) but the “ideational representative” of the drive. Lacan proposed that repression is what distinguishes neurosis from other clinical structures – psychotics foreclose, perverts disavow and only neurotics repress] Lacan maintained that it is very important not to confuse repression with the conscious judgement of a Subject that rejects and chooses. |

Sublimation |

The concept of Sublimation was first introduced by Freud in 1905 in his essays on Sexual theory. Sublimation is the act of unconsciously deflecting raw, irrational and uninhibited sexual and aggressive impulses/drives towards different, socially acceptable expressions and human activity [e.g. artistic creations, sports and intellectual work] that has no connection to sexuality but gets its power from the psychic energy in the sexual drive [la pulsion sexuelle]. Sublimation thus works as a socially acceptable escape valve for excess libidinal (sexual) energy which would otherwise have to be discharged in socially unacceptable forms [e.g. perverse behaviour] or in neurotic symptoms. This means that complete sublimation would spell the end of all perversion and neurosis. While Freud believed complete sublimation might be possible for some particularly refined or cultured people, Lacan pointed out that absolute/complete sublimation is not possible for human beings, [since all healthy humans with a healthy brain, a functional hypothalamus and sexual organs will experience sexual urges and feelings] and that perverse sexuality to satisfy the drive is possible and accessible (e.g. prostitution, perverse behaviour, private fantasies, etc) but must be sublimated because it is prohibited or badly viewed by civilised society and is also not in the individual’s best interests. Lacan follows Freud in emphasising the fact that the element of social recognition is central to the concept of sublimation, since it is only when the drives are diverted towards this civilised dimension of shared social values that they can be said to be sublimated. This dimension of shared social values allows Lacan to tie in the concept of sublimation with Ethics. [Note: Perversion to Lacan is not simply a savage and grotesque natural means of discharging the libido, but a highly structured relation (reaction) to the manifestation of the sexual drives [instinct/need], which are in themselves in the form of language in civilised people rather than simple biological urges/drives. Lacan also revised Freud’s initial view that sublimation simply involves the redirection of the drive to a different (non-sexual object), but explains that the initial object that the drive was directed at does not change but only its position in the structure of fantasy [for the Subject] changes, i.e. only the nature of the object to which the drive was directed changes not the object itself; this is made possible because the drive is “already deeply marked by the articulation of the signifier”. In the average psyche, the sublime quality of an object is thus not due to any intrinsic property of the object itself, but simply an effect of the object’s position in the symbolic structure of fantasy for a particular Subject.] |

Table 1: A List of The Most Common Defence Mechanisms

Freud placed great emphasis on the development of the child because he was convinced that neurotic disturbances manifested by his adult patients had origins in childhood experiences. And as the last model proposed by Freud, the Genetic Model, explains, the psychosexual stages are characterised by different sources of primary gratification determined by the pleasure principle. Freud basically wrote that the child is essentially autoerotic. The genetic model has been previously described in the 3rd section of the essay, The 3 Major Theories of Childhood Development. [Please refer for more details]

However, the genetic model in psychoanalysis has been extensively revised and many of the concepts have given way to other theories [such as the Bowlby’s Theory of Attachment] nowadays that consider other sides in the development of personality. Other theories of peronality have also shown how personality continues to evolve and only stabilises around the age of 30. However, the genetic model of Freud laid the groundwork for other theorist such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth who based their guiding principles to uncover the theory of attachment on pre-oedipal developments first mentioned by Sigmund Freud. These attachment types have been discussed in the Essay, The 3 Major Theories of Childhood Development, and although it may not be completely true for all people, the logic behind the psychosexual stages should always be considered to some extent when analysing clients along with attachment types – not to forget to assess the self-reflective abilities of the person, since this has been proven to have more impact on self-adjustment related to adult personality, emotional intelligence and attachment types.

The Relationship between the Topographic Model and the Structural Model

It is important to assimilate the knowledge from the structural model and synthesise them with the topographic model. It can be seen that although the later model is conceptually distinct from the first model, they do map onto one another to some degree. The content of the Id, of course, lies firmly within the Unconscious, and is forbidden from entry to the consciousness unless disguised in the form of dreams, slips of the tongue, symptoms, and so on. However the Ego is not completely conscious unlike many ego psychologist may claim along with cognitive psychologist, as it has a strong Unconscious component, given that a great deal of psychological defence mechanisms are conducted instantly out of awareness, and hence is sometimes inaccessible to introspection by the patient – hence requiring a skilled psychoanalyst to guide therapy and treatment. The Super-Ego also has an Unconscious fraction, reflecting as it does and often “primitive”, and irrationally punishing through rigid morality – at least as much as it reflects our reasoned beliefs and principles. Although many concepts have been revised and alternative treatments relating to mental illness have also been devised by other schools of thought in psychology, the sheer complexity and uniqueness of the psychoanalytic system has formed a remarkable achievement. Indeed, Freud even had to invent new terminology to express his thoughts, and these terms have become an accepted part of our vocabulary.

Psychisme: Les théories de Freud ont-elles évolué? (2013)

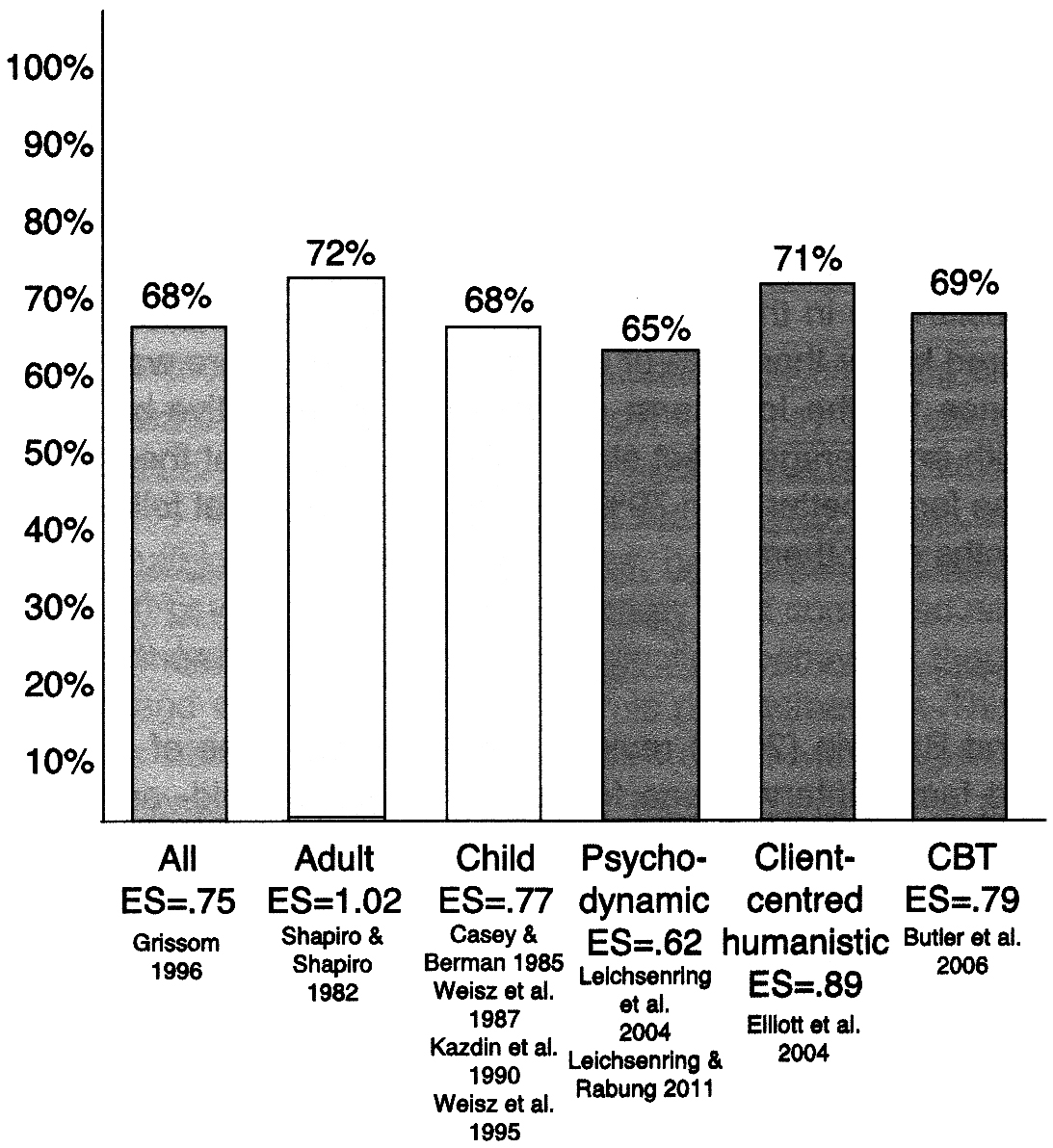

Psychoanalytic Evidence: From the perspective of Empirical Methodology (Mainstream Science)

Freud ardently believed along with all good psychoanalysts that psychoanalysis is a science, not an empirical science, but a science of the mind that slices not with blades or questionnaires, but with concepts through the linguistic and philosophical realm of a patients subjective reality. It is also fair to consider that Freud himself was an accomplished biological scientist before he developed psychoanalytic theories. Biological ideas are interwoven in his work, as is his concepts of drive, instinct, and psychic energy. Nevertheless, the methods that he used to obtain evidence for the psychoanalytic theory were very different from the reductionist and empirical methods used by the government institutions, laboratory scientists or the statistical psychologists with their quantified questionnaires exploring basic “traits”. As an anatomist and physiologist, Freud made systematic observations of living and dead organisms, and conducted controlled empirical experiments. Hence, he must have come to the same conclusion as ourselves, which is, mental life cannot be fully explained by the mechanical explanations, although a lot can be learnt from understanding the physiology of the brain, but the “software” itself, that generates the mind, is an entity that empirical science comes short in terms of its methodologies. Hence, as a psychoanalyst, Freud introspected and speculated about his own mental life, and listened closely to what his patients told him during sessions of psychoanalytic therapy. It is quite clear, that dissecting an eel is completely different from dissecting a personality with all its complexities, and that observing the stream of one’s consciousness or another’s speech [i.e. discourse] is very different from conducting a controlled experiment with observable variables. So, psychoanalytic evidence is clearly unlike the evidence on which most “hard physical sciences” are based.

However, it is important to understand that the critique of psychoanalysis from the methodology of empirical science may not be rational. Because psychoanalysis was never intended to be a mechanical “hard” science, although it learns from neuroscience and cognitive-psychology of certain very basic aspects of the physiology of the brain and its functions. These questions about Empirically Supported Treatment (EST) came to the forefront of psychotherapy literature in 1993, when Division 12 of the American Psychological Association worked to publish a list of criteria for what constitutes EST (Chambless, et al., 1996; Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, 1995; Taskforce on Psychological Intervention Guidelines, 1995). A list of treatments were published that we empirically supported and very few psychodynamic treatments were included, nor were interpersonal or humanistic therapy included. Not surprisingly, these guidelines and list became anything but unifying for psychotherapists and psychotherapy researchers.

Westen, Novotny and Thompson-Brenner (2004) made some important critiques of the literature on ESTs. They noted that ESTs are often designed for a single, Axis I disorder, and patients are screened to maximise their homogeneity and to minimise their diagnostic comorbidity. Treatments are manualised and brief, and outcomes are assessed often by reductions in the primary symptom reduction for that particular disorder. Westen et al. suggested that EST researchers always tend to assume the following:

- Psychopathology is highly malleable

- Most patients can be treated for a single problem or disorder

- Psychiatric disorders can be treated without much attention to underlying personality factors

- Experimental methodology used to develop ESTs has ecological validity in clinical practice

Westen et al. (2004) basically contended that these assumptions are not valid, not to say wrong. There is considerable diagnostic comorbidity, making most patients ineligible to participate in EST research trials. There also is considerable stability of psychopathology of psychiatric symptoms, even after “successful” completion of EST. And clinicians of all theoretical orientations see patients well beyong the time allotted in treatment manuals (see Morrison, Bradley, & Westen, 2003; Thompson-Brenner, Glass, & Westen, 2003; Westen & Morrison, 2001 for an excellent review of these issues).