Mis à jour le Samedi, 8 Avril 2023

About the life of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on February 22nd of 1788 in Danzig, Germany, he was the son of Henri Floris Schopenhauer aged 38 and Johanna Henriette Trosiener who was then 19 years old. His father was a wealthy merchant and banker who had already planned for his son to become a business man before his birth, and hoped Arthur would follow in his steps. Henri Schopenhauer was also an independent minded man who moved his family from the city of Danzig when it was taken over by Prussia in 1793. The new family home was in Hamburg. Arthur Schopenhauer left to visit England and other countries, on the understanding that when he completed his tour, he would begin work in a business. The latter, then 16 years old, kept his promise but being much more intellectually oriented, he did not have a mercantile mind and had no interest for business and so when his father died, he got consent from his mother to continue his studies.

In 1809, he entered the University of Göttingen to study medicine, but he changed to philosophy in his second year, as he put it “life is a problem and he decided to spend his life contemplating it”. He also studied at Weimar where he lived with his mother until he became estranged from her. Schopenhauer had a moody, irritable temperament and could be violent in his passion.

At the university, Schopenhauer developed an affection for Plato and visited Berlin to hear the lectures of contemporary philosophers Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762 – 1814) and Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768 – 1834). Fichte was the first transcendentalist idealist and Schleiermacher was a founder of modern Protestant theology. Schopenhauer found Fichte’s comment, “No one could be a true philosopher without being religious” absurd and retorted that no man who was religious turns to philosophy since they have no need for it [a questionable statement when religion (e.g. Christianity) does not cover all the aspects of the experience of life in detail, or study God’s works methodically through the lens of science and rationality, to understand the further implications in the betterment of the human world].

Image: “Les Mains” par Auguste Rodin

Schopenhauer left Berlin when Prussia rebelled against Napoleon. He never developed strong German patriotic values and sentiments [perhaps never given or found a reason to do so], and always regarded himself more as a cosmopolitan without any strong national affiliation. In that sense we can deduce that Schopenhauer’s vision resonates with the French intellectual heritage because it tends towards universalism; like Montaigne, Descartes and Voltaire, he genuinely had a universal vision of humanity and did not restrict himself to the particular collective frame of mind of a group of organisms conditioned within the limits of a geographical region, which is also similar to the vision of Socrates who said: “I am not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world“.

Traduction (EN: “I am not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world.” – Socrates

The thinker went into retirement to write his first dissertation called “On the fourfold route of the principle of sufficient reason”, which was published in 1813 and earned him a doctorate at Vienna. The poet Goethe congratulated Schopenhauer, and in return he wrote an essay called “On Vision and Colours” which supported Goethe in his stand against Isaac Newton. But the dissertation, although it won the admiration of Goethe, went practically unnoticed. The author however always considered it the groundwork and essential introduction to his philosophy. Shortly after he published his dissertation, Schopenhauer met an Oriental scholar, Friedrich Majer (1771 – 1818), who introduced him to Indian philosophy and literature. He maintained an interest in Indian philosophy throughout his life, and as an old man, he meditated on the Upanishad, part of the Vedas [the sacred script of the Hindus]. He would later associate his theory of the world of ideas with the Indian doctrine of Maya [to the Indians, Maya is illusion or the world as an illusion]. To Schopenhauer, this meant that the individual subject and object he wrote were “Maya”, all at the end.

For 4 years between 1814 and 1818, Schopenhauer lived in Dresden, which is where he wrote his masterpiece “The World as Will and Idea”. He sent the manuscript to his publishers and left for an art tour of Italy. The book was published the following year in 1819, and although it received attention from some philosophers, it sold very few copies. This was a disappointment to the author who felt sure it contained the secret of the universe.

This failure did not kill his eagerness however, so he returned to Berlin and started lecturing. By now he was 32 years old. He deliberately scheduled his lectures for the hour at which the philosopher Hegel was also accustomed to lecture – planning to compete with the master. But his lecturing career was a failure and Schopenhauer gave it up after only one semester. His ideas seemed at odds with the dominant spirit of the time.

Schopenhauer roamed around a bit and then settled in Frankfurt in 1833, he read European literature and scientific books and journals looking for illustrations or confirmations of his theories. He frequented the theatre and also continued writing, publishing on the Will of nature and winning a Norwegian prize for an essay on freedom. He failed to win a similar prize from the Royal Danish Academy of the Sciences for a separate essay on ethics; they disapproved of his disparaging remarks about other philosophers. These two essays were later published together in 1841, under the title “The two fundamental problems of Ethics”. In 1844, Schopenhauer published a second edition of “The world as Will and Idea”, which contained 50 new chapters. In the Preface, he took the opportunity to make a strong statement of his views about university professors of philosophy, which were of course not admiring.

In 1848 there was an unsuccessful revolution in Germany. A revolution from which Schopenhauer had no sympathy whatsoever. But after the failure of this revolt, people were more willing to consider a philosophy which emphasised the evil in the world which preached the rejection of life for the route of contemplation. Schopenhauer’s popularity was on the rise.

In 1851, he published a collection of essays that dealt with a wide variety of topics, and finally in 1859, he published third edition of the “World as Will and Idea” with more supplements. In the last decade of his life, the author finally became a famous man, all kinds of visitors with all kinds of philosophies came to see him and to enjoy his brilliant conversations. Lectures were given on his system at the University, the very university he has attacked, a sure indication that he had finally achieved success. Schopenhauer has spent a long, lonely life of reflection and only after his works were ignored for many years that he attained fame and reputation. He died in September 1860, at the age of 72.

Image: Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) by Mitch Francis

Schopenhauer, was a realistic philosopher, focused on the raw nature of life: the mental evils and cruelty that lies within man, which he considered inevitable sides of human nature that psychologists view as mental disorders with a negative effect on both the character of the ill mind and the human environment at large exposed to that vile animalistic side of human nature. Schopenhauer’s negative view of man’s behaviour and role in life was a sharp contrast to the other more euphoric and at times unrealistic philosophers who marked the spirits of the generation before him, focussing on a an idealistic and exaggerated side of man’s mind and character.

Although Schopenhauer’s work originally gained little attention at the time it was published [perhaps for being too avant-garde for the atavistic institutions of his time when neither the theory of evolution was known nor evolutionary psychology], he expressed an interpretation of the world that was dragging, and embodied an opposition to the major intellectual figures who had imposed their thought before him: great names in philosophy such as Victor Schelling and Hegel. Schopenhauer opposed their thoughts on important points but did not deny expressions of art such as the romantic movement in its various forms. Schopenhauer who never refrained from publicly criticising people and ideas he disliked was very vocal in his complete contempt for these men, and regarded himself as their great opponent in the ring of the leaders delivering the “Real truth” to mankind and civilisation. Schopenhauer’s work in many ways could be viewed as an extension of another famous German philosopher, namely Immanuel Kant, who preceded him by one generation, delivering his major philosophical work, “a critique of pure reason”.

As a man, Schopenhauer was cultured, broadly educated, eloquent and articulate, witty and conversational, and a very talented writer, but he was also opinionated, egotistical, and often quarrelsome. His remarks about other philosophers were assaulted and his remarks about women in general were so scathing that they had to be deleted from his book by his editor. He was obsessed with the suffering of humanity, but did nothing to alleviate it. He himself made the comment that it is no more necessary for a philosopher to be a saint than it is for a saint to be a philosopher, and he never tried to prove otherwise. But, in the final analysis he was exactly the man he needed to be to write what he wrote.

Arthur Schophenhauer’s pessimistic and grim interpretation of life are not very likely to have come from a man of infallible tolerance or patience, and that interpretation of life played a significant role in the development of human thought and philosophy by keeping the debate open and providing inspiration to viewpoints that forced humanity to re-examine itself yet again.

The “Will to Live”: Schopenhauer’s concept, Human Love, Science & Evolutionary Psychology

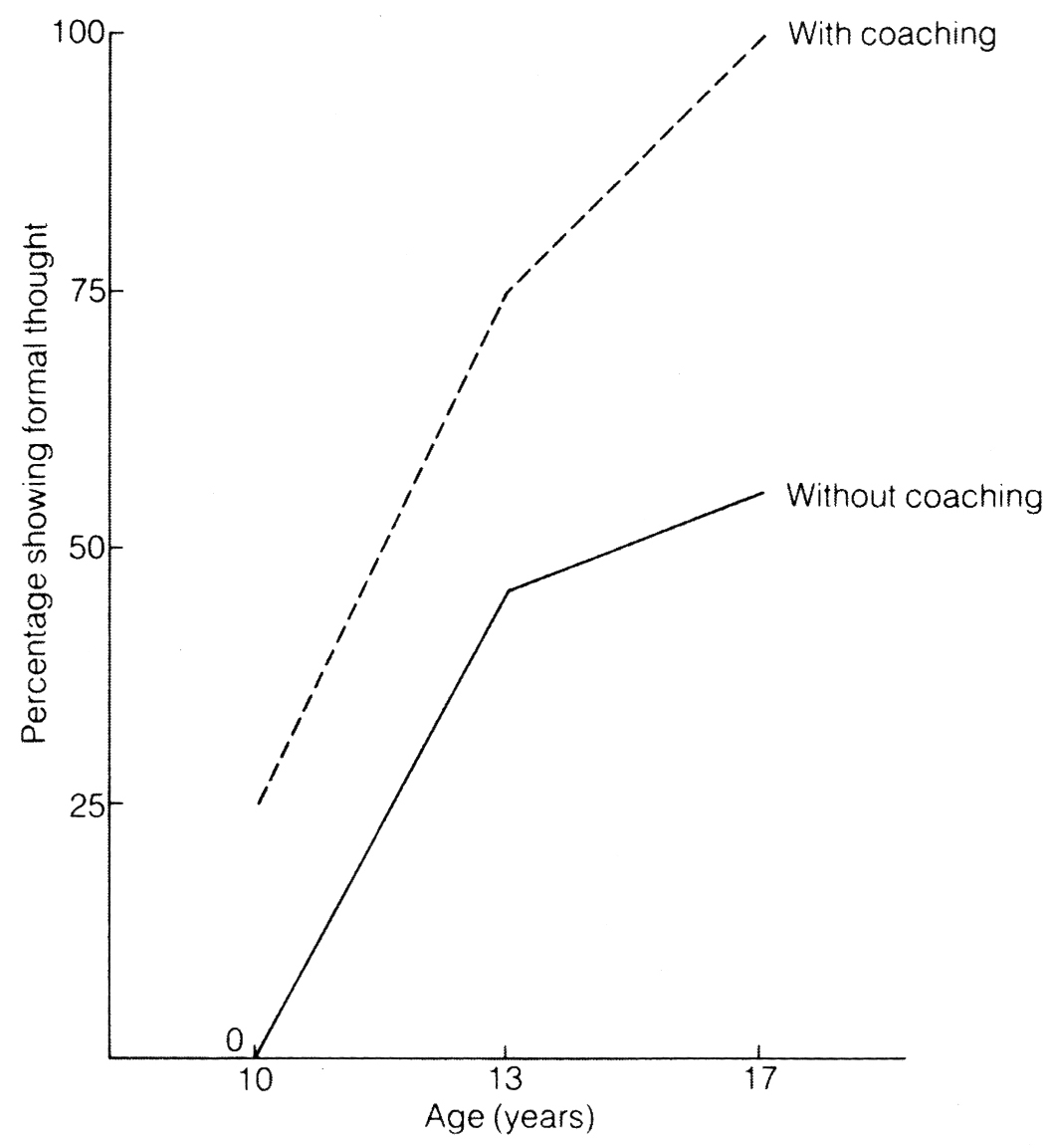

The concepts of Arthur Schopenhauer’s major work, “The World as Will and Idea” constitutes the foundations for the future works of major thinkers in both psychology and philosophy. As a modern thinker, it is fundamental to get a good understanding of the core concept that structure the work of Schopenhauer, more precisely his philosophical concept of the “Will To Live“, which is echoed in evolutionary biology [i.e. in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which is widely accepted by the scientific community worldwide]. Schopenhauer was incredibly avant-garde because at the time he composed his philosophical treaty of the “World as Will and Idea”, Darwin had not yet formulated the theory of evolution, which would only be published in 1859 – just one year before the death of Arthur Schopenhauer.

The importance of grasping the concept of Schopenhauer’s “Will To Live” cannot be escaped as that “Will” is also synchronised with our philosophical orientation in regards to desire and motivation for the “Organismic Theory of Psychological Construction“, since it resonates with the fundamental belief of the mind as an active, dynamic and self-generating entity, and this is in the German intellectual tradition of mental life [it was also a founding assumption for Jean Piaget as he developed his Theory of Cognitive Development in Children]. Freud also saw psychoanalysis as a revolution of the mind that had to disturb the consciousness of the world, and viewed the unconscious as a reservoir of impulsive force repressed in the biological depths of the soul – a notion that also relates to Schopenhauer’s “Will To Live”.

When Darwin published his theory of evolution, he was opposed to all the reigning ideas of the times, and faced a lot of criticism from religious scholars as he demonstrated that life appeared on Earth by complete chance and in an absurd manner. Life then developped and became more complex and sophisticated through the process known as natural selection. Darwin radicalised his vision of the world since he would go on to even discard any “Will” and his theory of evolution explains life based on the simplistic mechanic of “natural selection”; for example, natural selection allowed human beings to have organs such as eyes simply because such an organ gave man the ability to escape predators – there is absolutely no “Will” behind this procedure and no finalised plan.

What is genuinely interesting about the philosophical theory of the “Will To Live” in Schopenhauer’s work is that it would eventually come to resonate with the much later works of Charles Darwin. The scientific translation of the “Will to Live” in Schopenhauer’s work is what Darwin called the “struggle for life”. Hence, this connection between Schopenhauer’s thought and Darwin’s theory allows us to understand that for both of them, everything that human beings have inside their bodies is at the service of this “Will to Live” [i.e. survival instinct]. Hence, to acknowledge Schopenhauer’s sharp insight as a truly avant-garde thinker, we have to note that he set the foundations for the field nowadays known as “Evolutionary Psychology“ at a time when it was inexistent.

What are the principles of evolutionary psychology? Simply to fully extrapolate and firmly apply the logic of the theory of evolution to work out its consequences. The theory of evolution explains that all the organs present in the human body are the simple consequence of the evolutionary process of “natural selection” because those organs allowed the species to survive, i.e. we have eyes, a nose, ears and a mouth because those organs allowed homo sapiens (i.e. humans) to survive. So, evolutionary psychology goes even further to apply that survival and evolutionary logic to develop the school of thought on the foundational argument that, since the brain is also an organ that allowed us to survive, so what mankind has in the mind (i.e. our psychology itself) is also the direct result of the evolutionary process of natural selection. Thus, evolutionary psychology claims that the homo sapien mind (i.e. human psychology) is structured in such a way because it favoured the survival of homo sapiens.

The “Will to Live” what we could also call the “instinct for survival” is a profound force deeply embedded in the biological depths of all homo sapiens. That “Will to Live” impacts behaviour at both an individual level and at the level of the species (i.e. homo sapiens). The will to survive of the species is stronger than the will to survive of the individual – which means that the individual wants to survive but there is an unconscious will which is even stronger in the mind which aims not to ensure the individual’s survival, but to ensure the survival of homo sapiens. If we were to express this phenomena from the perspective of natural selection in Darwin’s theory of evolution, it would explain how nature, over the course of evolution, has selected and favoured individuals who were most apt in showing empathy towards their fellow human beings [e.g. towards their children] because such empathetic behaviour promoted the survival of the group [the species itself].

Schopenhauer pointed out that this “Will to Live” has no specific objective except that of preserving itself; which means that man reproduces life for life itself [i.e. one has children so that those children can have children and their children can also have more children, and so on – an infinite process without any precise objective or end result]. As such, no life has any sense, no life has any precise or known final objective; humans pass down the task of devising sense to the next generation and so on – the question of sense is completely inexistent.

Since, life has no clear final objective and no clear sense, Schopenhauer observed that life is absurd because it is mainly an experience of various kinds of suffering. Hence, his famous formula that life is like a pendulum that oscillates from right to left between suffering and boredom: what does this mean? It means that life is made of desire, and desire is always a lack [e.g. a poor person’s desire to have money results from the lack of money in order to be able to stay alive].

This idea of desire as lack will also be echoed in the works of Jacques Lacan as an explanation to human motivation. Hence, as Schopenhauer explains, lack is a form of frustration and suffering. When a human being desires, that person suffers, and when that desire is satisfied, peace and calmness are obtained and the person is in a state of serenity [for some time], but eventually that state of calmness does not last forever, and boredom soon engulfs the individual because nothing leads to moving forward in that state. It is desire that motivates man, it is desire that allows man to live and move forward, and so man oscillates between suffering [when one desires] and boredom [when a desire is accomplished].

If human psychology [i.e. the mind or psyche] is also direct result of evolution which includes the “Will to Live”, then what purpose do feelings and emotions serve? Much before Darwin and much before evolutionary psychology itself, Arthur Schopenhauer through his meditations asked and answered questions about the purpose of feelings and emotions in the human mind:

– In what way do feelings and emotions help us to survive?

– Is romantic love simply an elaborate illusion at the service of our survival instinct?

All human emotions and feelings are nothing more than illusions at the service of the will to live [or we could say the instinct for survival in evolutionary terms]. What Schopenhauer posits, is that when one understands [i.e. becomes aware] how one is being manipulated by emotions and feelings at the service of the “Will to Live”, it becomes possible to detach oneself from those emotions and feelings. But unfortunately, as Lev Fraenckel points out, detachment also leads the human mind to kneel to the demands of the cold and icy calculations of science in the quest to discard those feelings and emotions manipulating us; that could also compel us to become robotic, mechanical and purely utilitarian in our outlook and behaviour – which nature itself did not design human beings with such a mode of operation. Can we can find a balanced mode of existence to maintain our humanity in a life experienced with emotions while also embracing rationality and reason? This will be elaborated and discussed below in our constructive critique building on Schopenhauer’s foundation while also linking concepts from other disciplines and thinkers.

By the logic of the philosophy of Schopenhauer and evolutionary psychology, human emotions are fake (i.e. a seductive, elaborate and beautiful illusion), because they are simply nature’s manipulation to drive the individual to protect his fellow human beings so as to promote the survival of the species. It is exactly the same for romantic love because we have the impression of following and going after our own individual pleasure and romance when in fact it is also nature’s manipulation (i.e. a trick in the shape of a powerful spectacle of nature inherited through thousands of years of human evolution and natural selection) to push individuals to mate and reproduce – a powerful drive at the service of the will to live (or survival instinct). Lev Fraenckel, the French philosophy professor suggested that as a modern example, we could consider the reason why Jack in James Cameron’s film from 1997, Titanic, went as far as to die for Rose out of love; the reason behind his dramatic sacrifice lies in the fact that he was manipulated by his unconscious at the cost of his own life (i.e. the will to live or survival instinct as nature’s manipulation in the form of emotions that drive man to protect our fellow human beings).

Hence, from Schopenhauer’s perspective and even from the standpoint of evolutionary biology, sexual pleasure is simply a bait used by nature to promote reproduction among human beings [which makes a lot of sense in justifying the presence of sexual drives in human beings and animals alike since without them, a species would be devoid of the desire to procreate and become extinct]. That idea may shed some light on man’s love choices in a fairly interesting manner according to Schopenhauer, since it suggests that a male will fall in love with a female with whom he may hardly care about simply because it serves the interest of our species, i.e. the human race. The male will fall in love scientifically (and in many cases unconsciously, driven by his evolutionary instincts or manipulated by his will to live) with the signs of female fertility, i.e. hips wide enough to procreate and breasts adequate enough to breastfeed.

Image: Des mères allaitant leur bébés / Mothers breasfeeding their babies

In an episode of the French show, Arrêt Sur Image, Sébastien Bohler, the chief editor for the magazine Cerveau & Psycho and doctor in neurology explained how “in general”, men tend to be attracted to females with particularly shaped hips, scientifically caracterised by the waist to hip ratio. It is a value obtained by dividing the waist circumference by the hip circumference, and the ideal waist-to-hip ratio is 0.7 in all cultures apparently (Singh and Singh, 2011). As for females, according to evolutionary logic and Schopenhauer’s perspective, their primary biological instincts tend to make them fall in love with males who bear the apparent signs of virility and who manifest a fairly high level of testosterone in order to ensure the protection and security of the offspring. As such, females are also manipulated by their “Will to Live” towards a particular form of masculinity, which generates the female reproductive instinct.

This allows Schopenhauer to give a strong biological reason to the observation that the rate of infidelity is always higher among men than among women even if it is tending more and more towards equality, but still not the case.

Graphique montrant la démographie de l’infidélité en Amérique / Source: Institute for Family Studies

Logically, going by the physiological limitations of the female body, once a female falls pregnant, it becomes impossible for her to continue reproducing for 9 months; she can only produce an offspring once at a time. As such, it is in her best interest to remain with the same partner. On the other hand, in the male’s case, the dynamic is different, because his physiology does not halt or impose any limitation on his inherited reproductive instinct derived from thousands of years of evolution as a mammal, which allows him the choice to continue reproducing with more female partners. As such, Schopenhauer extracts meaning from this evolutionary logic at every level, and in his line of thought it becomes clear that males are also being manipulated by their survival instinct [i.e. their deeply rooted instinct of sexual selection], which renders them highly reactive and receptive to female signs of fertility, which Schopenhauer points out as the main cause for males’ attraction to young females. The simple and fundamental scientific reason behind such attraction being that the apparent desirable signs of female fertility [i.e. perfect waist-to-hip ratio and adequate breasts for feeding and raising offsprings] are mostly found in young females; although in the modern world, with widespread education about nutrition science, eating patterns, intermittent fasting and fitness, in some societies, for e.g. France, older females are preserving their signs of fertility longer. Fertility after the age of 40 has been rising steadily since 1980 in France.

Graphique: Taux de fécondité par âge à 40 ans ou plus de 1920 à 2020 / Source: INSEE

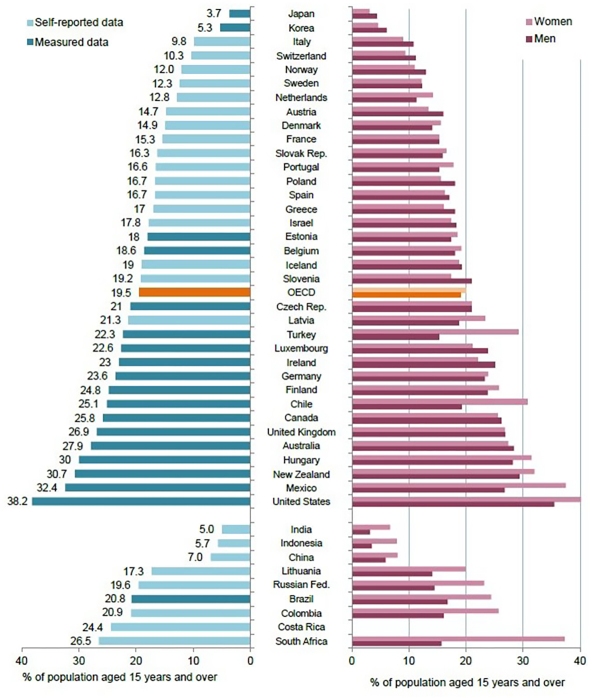

Le graphique présente les taux d’obésité (IMC>30kg.m-2). La moyenne des pays de l’OCDE est de 19,5% d’obèses. Les Etats-Unis, le Mexique, la Nouvelle Zélande et la Hongrie sont les pays les plus touchés avec respectivement 38,2, 32, 4, 30,7 et 30% d’obèses. Le Japon, la Corée, l’Italie et la Suisse sont les pays les moins touchés avec 3,7, 5,3, 9,8 et 10,3% d’obèses. La France est à 15,3% de taux d’obésité (donnée OCDE basée sur du déclaratif légèrement inférieure aux résultats d’ESTEBAN, basé sur des mesures) / Source: Centre de recherche et d’information nutritionnelles (Cerin)

This inherited “Will to Live” or survival instinct in homo sapiens is also one of the reasons why human beings have an instinctive attraction to beauty, since beauty has a biological basis. Human beings are attracted to the averageness and symmetry of faces, and by the harmony of the body because those signs are linked to good health and internal condition. A study carried out in 1994 by biologist Randy Thornhill supported the hypothesis that human beings prefer averageness and symmetry in faces (Grammer and Thornhill, 1994). Thornhill explained that this attraction and the selective criteria biased towards physical beauty has been observed and is also common among animal species; it is now known that symmetry is linked to better performances in terms of reproduction, survival and resistance to disease – we can now conclude that there is a similar pattern among homo sapiens, i.e. human beings.

As opposed to many common opinions, scientifically we find that beauty is not subjective at all because those criteria for sexual selection are similar across all human cultures., i.e. waist-to-hip ratio, averageness and symmetry of faces, and the harmony of the body.

Hence, Schopenhauer’s argument leads to the position that “love”, on the surface as experienced from the individual perspective of human beings, may seem like a romantic ideal, but this illusion is simply the elaborate spectacle used by the “Will to Live” to manipulate our species towards its survival by favouring mating – in order to replicate the lifeform that contains the will. This comes to echo Spinoza’s thought when he said: “Men are mistaken in thinking themselves free; their opinion is made up of consciousness of their own actions, and ignorance of the causes by which they are determined.”

« Les hommes se trompent quand ils se croient libres ; cette opinion consiste en cela seul qu’ils sont conscients de leurs actions et ignorants des causes par lesquelles ils sont déterminés. » – Spinoza / Traduction (EN): “Men are mistaken in thinking themselves free; their opinion is made up of consciousness of their own actions, and ignorance of the causes by which they are determined” – Spinoza

It is very important to not apply those criteria for sexual selection blindly [as we would for animals], to every single individual because human beings with good reflective self-function [i.e. the ability to reflect on conscious and unconscious psychological states, and conflicting beliefs and desires] have the ability to rise above their basic biological instincts and change their internal working models, and consequently their behaviour. However, it would also not be perceptive or realistic to completely ignore the presence of this powerful biological force in homo sapiens, because no matter how much human beings manage to detach themselves from it (i.e. the biologial will to live, or survival instinct), it is embedded through thousands of years of evolution in the biological depths of the human mind and operates most of the time at an unconscious level.

Sigmund Freud’s founding psychoanalytic concept states that intra-psychic conflict within the human mind is inescapable, which is a fundamental concept in psychoanalysis also taken over by the flamboyant French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who also argued that desire is inextinguishable. Psychoanalysis is also founded on the fundamental concept that human beings are driven by forces beyond their own understanding and are a mystery to themselves, with a reservoir of instinctual “psychic energy” grounded in basic biological processes; the sexual form of this energy is referred to as “libido“. The case of Sigmund Freud’s patient Elisabeth von R. illustrated this well: torn on the one hand between her high morality, which dictated that she preserves the balance of her family, and on the other hand her deep erotic desire for her brother-in-law, of which she had been completely unaware of (unconscious). That unconscious conflict provoked a strong feeling of guilt in her such that she started suffering from violent physical symptoms.

Hence, the concept of the deeply embedded “Will to Live” which is accepted as the “Survival Instinct” of homo sapiens in evolutionary psychology, is also echoed in psychoanalysis. The major motivational constructs of Freud’s theory of personality was derived from instincts, defined as biological forces that release mental energy. Psychoanalysis implies that conflict within the mind’s opposing forces is inevitable:

- i.e. the wild Unconscious (known as the Id or the “Ça” in French, where the “Will to Live” or survival instinct is located) will get into conflict with the Super-Ego (the preconscious or the “Surmoi” in French, which acts as the person’s conscience and the internalization of society’s rules); and the Ego (which is the conscious part of the mind but also with a partially unconscious side) will have to mediate between those two. The Ego now becomes the servant of three masters: the Id, the Super-Ego and the External Environment [Societal Rules]. It is now not enough to reconcile what is desired with what is possible under the circumstances because now the Ego also needs to take into consideration what is socially prohibited and impermissible. Instinctual drives must still be satisfied; which is a constant, however the Ego now attempts to satisfy them in a way that is flexibly “realistic” – that is, in the person’s best interests under current conditions – but also “socially” permitted. In the case of the majority of people, these prohibitions of various kinds are often very unreasonable and inflexible, rejecting any expression of the drive with an unconditional “NO”, either because the moral structures of a particular “culture” are intrinsically rigid, atavistic or unsophisticated, or because the individual’s internalisation of these structures is simply black-and-white, without any grey area to compromise for an adequate and acceptable form of expression of the drive. Thus, the Super-Ego imposes a pattern of conduct that results in some degree of self-control through an internalised system of rewards and punishments.

Intrapsychic conflict within the human mind is inevitable because the demands of society – or “civilization” – are generally opposed to the natural instincts and drives of homo sapiens. Indeed, intrapsychic conflict is one of the fundamental and defining concepts of psychoanalysis, and conflict within the mind is at the root of personality structure, mental disorder, and most psychological phenomena [e.g. artistic expressions of various forms]. The goal of personality is to reduce the energy drive through some activity acceptable to the constraints of the Super-Ego, which represents the conscience of the individual in line with what is acceptable or what can reasonably be made acceptable to society [This has been explained in detail in the Essay, Psychoanalysis: History, Foundations, Legacy, Impact & Evolution]

A explanatory review of the philosophical concept in “The World as Will and Idea”

Arthur Schopenhauer worked out a system in which reality is known inwardly by a kind of feeling where intellect is only an instrument of the “will to live”: the biological will to live and where process rather than result is ultimate.

Schopenhauer’s pessimism lies in his very strong rejection of life. In fact, this rejection is so strong that he even had to address the question of suicide as a solution to life although he never recommended it. He fortunately rejected this “suicidal solution” to life, which reflected influences rooted in Asian philosophy, particularly Buddhism and Hinduism. That is one of the most significant aspects of his work, being the first thinker produced by Western European intellectual heritage to assimilate Asian spiritual thought and leave a lasting impact on the Western mind. His preoccupation with the evil of the world and the tragedy of life is also reflected in ancient Hindu philosophies, and his writings stimulated an interest in Asian thought and religion in Germany, which can also be seen in the work of many later German philosophers.

In “The World as Will and Idea”, Schopenhauer also considered the important question of the function of art in far more depth than any of his predecessors; he even theorised a hierarchy for the arts, grading music, poetry, architecture [etc], from most important to least important. For that reason, his work had a profound effect not only on future philosophers, but also artists, particularly poets and composers, such as the enigmatic Wagner, who felt indebted to him and sent him a letter of gratitude when he was first introduced to Schopenhauer’s work.

Image: Tristan et Isolde (1912) par John Duncan

It is believed that Wagner’s popular opera “Tristan und Isolde” in particular, shows Schopenhauer’s influence as a philosopher who believed that music was the highest form of art, an idea that of course, Wagner found pleasing, and so the composer began to think of himself as a prime example of Schopenhauer’s concept of a genius.

People in other fields of the arts were also influenced by Schopenhauer, including the novelist Thomas Mann. Schopenhauer’s ideas had the unique ability to influence not only philosophy but many other fields of human endeavour and expression. Within philosophy itself, Schopenhauer’s intellectual originality cannot be classified or allocated to a specific school of thought “per se”, but his influence stimulates other philosophers towards a particular line of thought, which logically varied from one individual to another in terms of their response to Schopenhauer’s writing. The latter’s writing had a major impact on the enigmatic Friedrich Nietzsche, who was also a friend of Schopenhauer’s admirer, Richard Wagner.

Nietzsche shared the belief that life is tragic and terrible but can sometimes be transformed through art. Nietzsche was also the thinker famous, for his concept of the “Overman”. Unfortunately, Nietzsche’s writings and thought was taken out of context by his sister after his death to fit the ideologies of the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler. The “Overman” is in fact universal and not simply nationalistic as the true writings revealed after many scholars rejected the falsified and manipulated versions published by Nietzsche’s sister, Elizabeth [This was portrayed in Hedwig Schmutte’s documentary Nietzsche: Entre Génie et Démence, released in 2016].

Nietzsche’s concept of the Overman states that man is something that must be surpassed. That idea resonates strongly with Schopenhauer’s “Will to Live” (i.e. the wild survival instinct) as something that man must overcome, since those basic animalistic instincts along with other social distractions prevent man from becoming the Overman. Nietzsche’s philosophy sees the elevation to the state of the Overman as the result of one who rises above one’s lowest instincts and habits to reach a higher state of consciousness, in doing so, establishing a distinction from the mass mediocrity of the herd.

Those three names, Schopenhauer, Wagner and Nietzsche are often linked and are associated at times, through no fault of the men themselves with the controversial period of human history that saw the National Socialist regime come to power in Germany with unscientific ideologies and inhuman policies.

“The World is Will and Idea” begins with the famous line, “The world is my idea” when Schopenhauer says the world is his idea, he is referring to the relationship between an “object” and “the subject” [i.e. The person (subject) who perceives (or senses) the object and extracts meaning from it]. As an example, he did not mean that an apple is identical with your abstract concept of an Apple, he means that the apple as perceived by you exist only in relation to you as a person [the subject] who perceives it; its reality is only in what you perceive, it is what you perceive it to be so.

So, the world is my idea means that a whole visible world and its sum of total experience is simply “object” for a “subject”, its reality consists in the interpreted perception by a subject.

This theory of the world of idea was taken and developed from Kant’s philosophy, but the second part of Schopenhauer’s philosophy “The World as Will” is completely his own and expresses his very unique interpretation of human life. Briefly, this interpretation says that the will, i.e. “the will to live” is the strongest force in man and everything else is subordinate to it. Schopenhauer’s conception of the supreme wisdom of life lies in the ability of man to reject the irrational force in this “will to live” and escape from the tragic results of it.

The world is my idea. This truth applies to everything that lives and knows, but only man can reflect on it and bring his abstract consciousness to it. It becomes clear to him when he looks at the sun that what he knows is not a sun, but an eye that sees the sun, not a nurse but a hand that feels the earth. This truth is by no means new, it was a fundamental text of the Vedanta philosophy of the Hindus, it was also part of the reflections of the French philosopher René Descartes and finally it was also clarified by the philosopher George Berkeley – although neglected by Kant. But this view of the world as idea is one-sided and must be balanced by another one which is the impressive and awful truth that the world is my “Will”.

The world has necessary hands, the subject and the object. The object and the subject that perceives that object operate together. If one were to disappear, then the whole world would cease to exist. All objects have universal forms and either space, time and causality or the relation of cause and effect as Kant has demonstrated, they may be discovered and known apart from the objects in which they appear, as an expression of reason or the principle of sufficient reason. But what if our whole life is but a dream, or how do we distinguish between dream and reality? Kant tried to answer this question by stating that the connection of ideas, according to the law of causality, constitute the difference between them. But the long life dream in distinction from our short dreams has always had complete connection, according to the principle of sufficient reason. We are such stuff as dreams are made of and our little life is rounded with a sleep.

Life and dreams are leaves of the same book, the book we read through and the one whose leaves we turn idly to read a page here and there. Any system of philosophy that starts with the “object” has to deal with the whole world of perception, the most consistent form of these philosophies is simple materialism; which regards time and space and matter as existing absolutely. It ignores the object’s relationship to the subject (as perceived by it) in whom these ideas exist, then it takes a law of causality as its guiding principle: causality exists by understanding alone. Materialism seeks the most simple states of matter and then tries to develop all other states from it. It ascends from mere mechanism and chemistry: the chemical properties and attractions of objects. It ascends to vegetable and animal life, to sensibility and thought. But, the thoughts and knowledge reached through materialism in a long, laborious process, assumed from its starting point that there was a subject or perceived matter: eyes that side, hands that felt it and understanding that knew it.

The system of philosophy which opposes this materialism is idealism, which instead starts with the subject and then tries to derive or reach the object from the subject, but it overlooked the fact that there can be no subject without an object, like materialism this idealism begins by assuming what it is supposed to prove later.

The method of Schopenhauer’s system is different from both materialism and idealism, for it starts from neither object nor subject, it starts from the idea. The idea is the first form of consciousness and its essential form is the antithesis or opposite of subject and object. For each one of us, it is our own body that is the starting point in our perception of the world, and we consider it like all other real object, simply as an idea.

The understanding which develops ideas could never come into being if there were no simple bodily sensations from which to start. If the thinker were no more than a pure knowing subject without a body like a winged cherub that is all spirit, he would not be able to know the nature of the world. He would be like a man going around a castle getting to its façade and trying in vain to enter it, all reality would be a riddle.

But because the subject of knowledge is also an individual with a body and a bodily nature, the world becomes revealed, it is revealed in the will. Every true act of the will is a movement of the body for the action of the body is nothing but will expressed through an object. The body is the object, my body and my will are one. The double knowledge which each one has of his body out of idea and inner will becomes the key to the nature of the world. Phenomenal existence, the existence we perceive with our senses, is an idea and nothing more. Real existence or the thing in itself is the will.

Will is a term that applies to both the highest and lowest in man’s nature, it is that which drives us to pursue the light of knowledge and it’s also that which in nature strives blindly and dumbly to survive. Both come under the common name of will, just as the first dim light of dawn in the rays of the full midday are both called sunlight.

If we consider the impulse with which water hurries to the ocean, or the way in which a magnet turns to the North Pole, or the eagerness with which electric poles seek to be united, or the way a Crystal takes form, we can recognise our own nature, for the same will describes the inner nature of everything that is in the world. The world as will is one, it knows nothing of the multiplicity of things in the outer world: the world of perception, the world of time and space. Notions like more or less, don’t exist to it, it knows nothing of quantities or qualities. For this reason, it cannot be said that there is a small part of the will in a stone or a large part of the will in a man. Relations like this between part and whole belong to the idea of space which does not apply to the will.

In reality, the will is present in its entirety and undivided in every object of nature and in every living thing. Yet in terms of its objectification, that is, its external expression, it has different grades in inorganic matter, in vegetation, in animals and in man. The lowest of these appear in the most universal forces of nature, in the form of gravity, rigidity, elasticity, electricity and the like, which are in themselves manifestations of the will, just as much as human actions are. The higher grades are seen in man where the will takes the form of individuality and consciousness. It is here that the will shows its second side. For in the human brain lies the potential of comprehending the will, so that as it is kindled by a spark it brings the whole world as idea into existence. In this manner, knowledge proceeds from the will, knowledge that is either from the senses or is rational and is destined to serve the will in its aim of expressing itself.

In all beasts and in most men, knowledge remains in subjugation to the will, yet in certain individuals, knowledge can free itself from this bondage to the will, so the subject of knowledge exists for itself as a pure mirror of the world. As a rule, knowledge remains subordinate to the will and grows on the will [so to speak] as a head on the body. In the case of the beast, the head is directed towards the Earth where the objects of its will are. But in the case of man, the head is elevated and set freely upon the body as in the Apollo Belvedere where the head of the guard stands so freely on his shoulders that it seems delivered of the body and no longer subject to it.

Image: Apollo Belvedere (Sculpture Ancienne), Musée du Vatican, Rome /Apollon est le dieu grec des arts, du chant, de la musique, de la beauté masculine, de la poésie et de la lumière. Il est conducteur des neuf muses. Apollon est également le dieu des purifications et de la guérison, mais peut apporter la peste par son arc ; enfin, c’est l’un des principaux dieux capables de divination, consulté, entre autres, à Delphes, où il rendait ses oracles par la Pythie de Delphes. Il a aussi été honoré par les Romains, qui l’ont adopté très rapidement sans changer son nom. Dès le ve siècle av. J.-C., ils l’adoptèrent pour ses pouvoirs guérisseurs et lui élevèrent des temples.

The transition from the individual’s knowledge of particular things to the knowledge of the idea takes place suddenly. It happens when the knowledge of the will changes someone into a pure will-less subject of knowledge, contemplating things as they are in themselves. If raised by the power of the mind, a man leaves the common way of looking at things behind and forgets both his individuality and his will, then he becomes a pure “without will”, timeless and painless subject of knowledge – this appears in the genius; because when Genius appears in a man a far larger amount of the power of knowledge comes to him than is necessary for the service of his will. This extra knowledge is free and purified from will: a clear mirror of the inner nature of the world.

All willing arises from want (desire). The satisfaction of a desire ends it, but for one wish that is satisfied, there remain 10 which are denied. No attained object of desire can give lasting satisfaction, for it is likely alms thrown to a beggar that keep him alive today so that his misery may be prolonged tomorrow. Attending to the demands of the will continually occupies and influences our consciousness. But when we are lifted out of the endless stream of willing, we can comprehend things free from their relation to our will without any personal interest or subjective opinions, and then the peace we have been seeking comes of our own accord. For we are, at least for the moment, set free from the miserable striving of the will – the wheel stands still. There is no more slavery to the will.

It is the function of the fine arts to express this freedom from the will: the different grades along the way. Matter as such cannot be an expression of the idea, but when it is expressed through a form of art like architecture (its characteristics of gravity, cohesion and hardness), the universal qualities of stone appear as a direct but low grade of the objectified or expressed will. In the building, nature reveals itself a conflict between the gravity of the building and the rigidity of the structure of the support, as in the simplest form of a column. The problem of architecture, apart from practical utility, is to make this conflict appear in a distinct way so that the building material instead of a mere heap of matter bound to the earth is raised above it, so that the roof for example is realised only by the means of the columns or arches which support it. The pleasure that comes from looking at a beautiful building lies in the fact that the viewer is set free from the knowledge which serves the will and is raised to the kind of knowledge which comes from contemplation that has no will.

The highest grade of the expression of the will is found in anything that reflects human beauty in a way which reveals the idea of man. No object transports us so quickly into will-less contemplation as the most beautiful human form. We know human beauty when we see it, but true artists can express it so clearly that it surpasses even what we have seen. In the genius of a sculptor, we find a representation of what nature intended to express, so that if you were to present his statue to nature, he would say “This is what you wanted to say!”

Image: “Danaide” & “Le Baiser” par Auguste Rodin

In order to detach oneself from the “Will to live” which imposes suffering and meaningless striving, art plays a major role for Schopenhauer; the artist is not locked in a utilitarian relationship with the functional world, i.e. that of the “Will to Live”, but on the contrary, the artist will produce objects that have no functional use but that are simply beautiful. Schopenhauer defined beauty as a biological attraction for good health (i.e. the symmetry of the face, the harmony of the body, etc), and so we are still at the service of the desire imposed by the “Will” for reproduction. However, the artist will gain the ability to detach beauty from its functional goal (i.e. of reproduction): we can find the above sculptures by Auguste Rodin, “Danaide” and “Le Baiser” exquisitely beautiful, but we know that nothing concrete biologically (as desired by the “”Will”) can happen between oneself and those works since they are not living organisms. Hence, Arthur Schopenhauer noted that the artist does not participate in this tragic comedy of existence which consists of reproducing life at any cost, but instead, the artist is uninterested and produces objects of beauty in a completely uninterested frame of mind.

Painting as an art has character as well as beauty and grace for its object, for it attempts to represent the will of the highest grade in the idea of humanity. This, however, can be an abstract form of the concept known as the picture attempt [as it does at times an allegorical painting] to represent something other than what is perceived.

In poetry the relationship is reversed, for here what is given directly in words is the concept that leads readers away to the object of perception, this is done through metaphors, similes, parables, allegories and the like. The aim of all poetry is the representation of man. When it is a representation of the poet himself, we have the lyric. The lyric poet reveals himself in joy or more often grief as the subject of his own will, but along with this as the sight of nature impresses him, there is the awareness of himself as the subject of pure will-less knowing, and his joy now appears as a contrast to the stress of desire: desire imposed on him by his will. Epic poetry portrays man in a more historical context in connection with significant situations in human life. Drama in the form of tragedy is not only the best of poetic art, but the most significant in terms of this system of philosophy because it is the strife of the will represented at its highest grade of objectivity, it becomes visible in human suffering that is brought about by fate or error or wickedness, in which the will lives on while people fight against and destroy one another. The tragic effect in poetry may be produced by means of a character of extraordinary evil such as Iago in Othello or Creon in Antigone or by blind fate as in the Oedipus Rex of Sophocles or by circumstance and the situation in which the character finds himself such as Hamlet. In the tragic character we can observe how the noblest of men – after a long personal conflict and inward suffering – come at last to renounce the pleasures of life and the particular goals once so keenly fought for, instead the character joyfully surrenders to life itself. It is in this sense that Hamlet renounces life for himself but askes Horatio to remain a while and to – in this harsh world – draw his breath in pain to tell Hamlet’s story and clear his name.

Beginning with architecture, in which gravity and rigidity reveal the lowest grade of the conflict of the will with itself and ending with tragedy where this conflict reaches its highest grade, we have considered the arts and how they represent the will and the idea, but music stands quite alone, cut off from all the other arts, since it’s not a mere copy of any idea of existence in the world.

Music is as direct an expression of the whole will as the world itself is. Nature and music are two different expressions of the same thing, and so music speaks a universal language.

Traduction(EN): “What we could not say and what we could not silence, music expresses.” -Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

In the deepest tones of harmony in the bass we recognise the lowest grades of the will, for bass is in harmony with the crudest matter on which all things rest and from which they originate. The higher complimental parts of music are parallel with animal life and in the melody of high voice singing we recognise the high grade of the will in the effort and intellectual life of man.

The pleasure we received from beauty, the consolation we get from art and the enthusiasm of the artist, rest on the fact that whereas existence in the world is something sorrowful and terrible, the contemplation of the world as idea is both soothing and significant. But in the case of the artist, the contemplation of beauty doesn’t quiet the will and it doesn’t provide a pathway out of life as does the resignation of the saint. The deliverance from the will only occurs when – tired of the game – one renounces life and gets a grasp on what is real.

When the will – this blind and incessant impulse of nature – becomes conscious in man, it is recognised as the will to live. Man may affirm or deny it. He affirms the will to live when – having seen it as that which has produced nature and his own life – he then adds his own desires to it. The denial of the will to live occurs when the awareness or consciousness of it means the end of desire. The phenomena of the world – what we see and perceive – no longer motivates the will, for the comprehension of the world as idea has freed the will and allowed it to be silent.

It the essential nature of the will: nowhere free and everywhere powerful – to strive endlessly towards satisfaction that it is incapable of getting. Just as in nature, gravitation is the ceaseless striving towards a mathematical centre and this striving will not stop even if the whole universe were rolled into a single ball. In the same way the solid will become a fluid, the fluid will become a gas, and the plant – restless and unsatisfied – will strive through ascending forms until it goes to seed where it finds a new starting point.

All nature is a struggle in which war is waged that is deadly to both sides. All striving is in vain, and yet it cannot be abandoned and all this is identical to what appears in us. In us, the blind striving of nature becomes the will to live, but it is self-conscious will: we are aware of it! The fate of this will is in keeping with its striving nature in the face of constant obstacles and hindrances, and anyone who will consider the character and destiny of the will to live, will be convinced that suffering is essential to all life.

“Sadeness Partie I” par Enigma / Album : MCMXC a.D. (1990)

Translation (EN): “Has grandiose results by narrow lanes” / Source: Le Petit Larousse 2018 / Les locutions étrangères gravées dans nos mémoires ont la magie des formules oubliées dont le charme va croissant lorsque l’alchimie des mots nous est plus mystérieuses. Elles ont l’autorité de la chose écrite. / Mot de passe des conjurés au quatrième acte d’Hernani, de Victor Hugo. On n’arrive au triomphe qu’en surmontant maintes épreuves.

From where then did Dante take the materials for his hell? From the world! And when it came to describing the delights of heaven he had an insurmountable task, for the world could offer him no proper material. The fatal assertion of the will to live has produced man’s body and the desire to preserve and perpetuate it. So the assertion of the will is really the assertion of the body. In such assertion, we find the source of all egoism and all wrongdoing, but such selfhood is really an illusion due to a false philosophy in which the individual imagines he lives to himself alone. He is really only a product of the one will to live. Just as a sailor sitting in a boat trusting to his frail barque in a stormy sea, so it is that in the world of sorrows man sits quietly, trusting to the principle of individualisation and separateness, in which he only knows things superficially or as they appear to him, but when he comes to understand that the one will to live exists in all men alike, he realises that the difference between those that inflict suffering and those that bare it is only a perceived difference that is not real.

“La Barque de Dante” par Eugène Delacroix (1822)

In truth, the evil man is like a wild beast, who frenzied and excited, unintentionally buries its teeth in its own flesh, injuring itself as it tries to injure another. But no matter how veiled and evil man is by illusion, he still feels the sting of conscience, which creates a sense that the gulf which seems to separate him from others isn’t real.

As all hatred and wickedness rely upon egoism and as egoism rest on the assertion of the will to live, so do all goodness and virtue spring from the denial of the will to live. The will turns around and no longer asserts itself but denies its own nature instead. Man then denies his own nature as expressed in his body and no longer desires sensual gratification under any condition.

Voluntary and complete chastity is the first step in the denial of the will to live. But then the human race would die out, and with it the mind in which the world is reflected, and without a subject of knowledge, there would be no object, there would be no world. To those in whom the will to live has turned and denied itself [miserable and utterly dead inside], this world of ours with all its sun and milky ways is nothing.

These are some of the ideas and the basic themes presented in Schopenhauer’s “The world as Will and Idea”, a very lengthy work that of course includes many other ideas and elaborations of the ones we have mentioned. But the essence and main thrust of Schopenhauer’s philosophy can be found in a few basic points.

To begin with, he sees the will of man, and specifically the will to survive as the dominant force in the universe and slavery to this will is the root of all evil. Man and all other creatures are subservient to their will to live. In exercising his will, man inflicts all kinds of cruelties and evil. Schopenhauer first examined these cruelties in the world of nature, spending a lot of time on the way in which animals of one species prey on those of another. Then he moved onto man and says, “the chief source of the most serious evils which afflict man is man himself”. Whoever keeps this last fact clearly in view, sees the world as a hell which surpasses that of Dante through the fact that one man must be the devil of another. Schopenhauer uses war and various other cruelties such as industrial exploitation, bravery and social abuses to back up his claim.

Schopenhauer had no sympathy for the revolution of his time because he felt the state was justified, exactly because of the cruelty of man. It existed to make the world a little more bearable than it would otherwise be. He did not consider the state government divine, but he considered it necessary [a view he may have been willing to revise had he been alive in the 21st century with democracy falling apart and not being properly applied, leading to evil, unethical, unscrupulous and unskilled street politicians getting into positions above their understanding – forgetting that they are the servants of the people and instead believing that they should have power over the people].

Schopenhauer believed that we can take action to alleviate human suffering but that it is pointless to think that we can change the fundamental character of the world or of human life. If war was abolished for instance and if all of men’s material needs were met, they would eventually still resort to conflict – “it is their nature”. He is quick to condemn the optimism or idealism of other philosophers who disregard the ugly side of human nature, or who try to justify it as rational. To Schopenhauer these dark aspects of life were not secondary feature, they were the most significant aspects of human life in history. On this basis, he created his theory of The Blind and Striving Impulse, he called the Will. Then, he looked around and found support for his theory in the inorganic, organic and human phenomena of life.

Unquestionably, Schopenhauer held a one-sided vision of the world, but because of its one-sidedness and exaggeration it served as a counterbalance to philosophers like Hegel who focused attention on the glorious triumph of reason throughout history and he tended to dismiss evil and suffering with elaborate, evasive, phrasing. He did believe that the human mind could develop beyond what was required just to satisfy his physical and material needs; it could develop a surplus of energy over and above what was needed to fulfil its biological function. When that happened, man can use the extra energy to escape the life of desire and striving, of assertion of the ego, of conflict, none of which brings him satisfaction anyway.

Schopenhauer did offer 2 ways of escape from the slavery to the will:

(i) one was the path of contemplation, which is the way of art;

(ii) and the other was the path of asceticism, which involves renouncing the world in one’s personal desires or will (i.e. to completely get rid of the “will to live”). Man must stop willing to live, not only at the level of our species but more importantly at the individual level.

In transcending the Will through art [expressing it with insight], Schopenhauer was very specific about which art forms served what purpose, and in defining which were superior to others. Not surprisingly, the supreme poetic art is tragedy, for tragedy reveals the real character of human life expressed in dramatic form or as he said the unspeakable pain: the wail of humanity, the triumph of evil, the mocking mastery of chance and the irretrievable fall of the just and innocent.

However, art and contemplation, besides reflecting on the evil of life, can also open a door that becomes perhaps the only hopeful point in Schopenhauer’s entire book. This door is opened when man can see through the veil of Maya [illusion]. That is precisely where Schopenhauer finds much inspiration from hinduism and buddhism; in those philosophies of Asia, there is the notion that in order to attain the state of nirvana, one must extinguish the “will to live” and thus one’s irrational desire, which is simply a form of manipulation that is referred to as “Maya”. We find this idea resumed in the four noble truths of Buddhism.

Maya, being the Hindu concept for the illusionary nature of the world and life. It is Maya [i.e. the illusionary manipulation of the will to live] that causes one to see separateness and division where there is none. Schopenhauer observed that man had the intellectual capacity to develop gradually a site that penetrated this illusionary manipulation that is Maya. He raised some very important questions:

– What is the purpose of achieving such virtue?

– What happens afterwards?

To start with, the man who denies the Will treats the world as nothing, for the world is just the appearance of the will, which he denied. So it is true that when we discard our will to live, it is a scenario when the will denies itself, and when this happens our world with all its sun and Milky ways means nothing! But then what happens at death? Schopenhauer is convinced of the finality of death. “Before us”, he says “there is indeed only nothingness”. Death or the withdrawal from the world means the extinction of consciousness. In life, he reduces existence to thin thread, and at death, it is finally destroyed.

The man who denies his will to live reaches the final goal, which is to not live. This is where Schopenhauer finds strong inspiration from Asian spiritual philosophy, more precisely in Buddhism, which is to say that when one renounces the “Will to Live”, life becomes much more enjoyable and serene. This is a powerful remedy since it allows us to put all our suffering into perspective when we are at our worst [for e.g. in deception in love matters when one realises the feelings are simply the manipulation from the will]. However, like all great remedy, extreme abuse can have a negative effect since we can overdose on them, which would lead us to completely shut down our “Will to Live”, and that can lead to suicide because human experience and life itself would lose all meaning and taste: no desire and no motivation. A clinical investigation among community-dwelling older adults in the US found that the will to live decreases with age, and that decrease in the “will to live” predicts depressive symptoms (Carmel, Tovel, Raveis and O’Rourke, 2018). However, those older adults studied were not meditating from a conscious desire to extinguish their will to live, and as such developped depressive symptoms.

Image: Image: Dieu hindou, Seigneur Shiva en méditation [Shiva est le dieu de la destruction, de l’illusion et de l’ignorance. Il représente la destruction mais le but de celle-ci est la création d’un nouveau monde. Voir :History on Western Philosophy, Religious cultures, Science, Medicine & Secularisation]

When extreme meditation allows such spiritual individuals like we find in Asia to detach themselves from the “Will to Live”, the whole world of perception changes within the mind and every single object that structures modern life [that to most people conditioned to the modern materialistic world gained a particular meaning that was passed on to them through their parents, teachers, the media, the government or books] loses meaning to the individual who goes to the extreme and extinguishes his will to live; the way his mind experiences life changes [i.e. perception and interpretation of everything in our world]. Those kinds of people may turn into passive lifeforms as close to plants and the very atoms that constitute every single particle in the universe, completely in harmony with nature and the cosmos, since they would find no meaning in life as defined by the industrialized world; they would have no desire and no motivation unlike most people, since by extinguishing their “Will to Live”, they renounced the suffering that comes with desire, and life is made of desire which is a lack, and lack is a form of frustration and suffering. That path may partially fit the direction of Nietzsche’s “Overman” in the search for nirvana.

Reaching such extreme levels of consciousness by rejecting the “Will to Live”, detaches the mind from all external influence in interpreting the universe and life, it can also lead to seeing everything simply as atoms, which constitute the whole universe, and hence generating the feeling of being one with the cosmic reality of the universe. In the case of organic life, which includes, plants, animals and human beings, those too are simply atoms [i.e. dust from the universe] that have gathered into living cells simply because the atmospheric conditions on Earth allowed such transformation. From such perspective, human consciousness is simply the product of the brain, which is the organic matter resulting from the assimilation of atoms from the universe expressing themselves through the limited senses of the human body.

Schopenhauer does leave one last hope beyond the grim disappearance of consciousness and of the world, admitting that it is possible that ultimate reality, which he called the thing in itself may possess attributes that we do not know about and that we cannot know. That reality would not be a state of knowledge since there would not be a subject and an object [that phenomenal and illusionary relationship that is required for knowledge], but it might resemble some experience that cannot be communicated and to which mystics refer to, but only in obscure vague ways.

In the end, like all great thinkers are expected to, Arthur Schopenhauer admitted that he did not have all the answers, but he thought he had some. Ultimately, it is the questions his answers posed to others that became his most significant contribution, for the role of the philosopher and of philosophy itself is not only to solve our problems, but also to express points of views that stimulate us to further thought and consideration on human nature and the meaning of life, in that, he was incredibly successful.

“Style is the physiognomy of the mind. It is a more reliable key to character than the physiognomy of the body.” – Arthur Schopenhauer

Concluding Thoughts on “The World as Will & Idea”

One of the interesting aspects of Schopenhauer’s philosophy is that it is in a fairly strong resonance with science, i.e. the theory of evolution, which is accepted among the scientific community, and it also set the groundwork for the field of evolutionary psychology. In that aspect, the philosopher was incredibly insightful and avant-garde.

Schopenhauer’s philosophical framework empowers individuals by providing a mode of thinking and perception that acts as a the tool to rise above grief & sadness from the many tribulations of life, especially love matters.

The concept behind the “World as Will and Idea” can become a very strong remedy for people depressed and weakened by love deceptions because Schopenhauer’s foundational framework clearly explains that those emotions and sentiments are simply an illusion (i.e. a manipulation) at the service of one’s survival instinct or “Will to Live”. Schopenhauer strenghens the individual by giving the individual the awareness of this manipulation of nature and hence the ability to rise above, discard and become detached from those feelings and emotions to heal their pain.

This is quite ironic, because while many personal development coaches advise us to reinforce our “Will to Live” to be better in life, the philosophy of Schopenhauer orients us towards the complete opposite, but only after developing the awareness of the consequences of renunciation that such action can lead towards personal empowerment. However, precautions must be taken to not completely extinguish our “Will to Live” since it can lead to suicide if we are not firmly aware of its implications and ready to cope with the life it imposes.

Schopenhauer does not recommend killing oneself even if he does not condemn the act in some texts – he even describes suicide as nonsense. However, he does not hide his admiration for the courage of the Hindus who go as far as to offer themselves as food to the crocodiles, or allow themselves to die of starvation voluntarily, or even throw themselves from the top of the Himalayas – as such the philosopher saw the end of life as a solution to the incessant suffering imposed by the will to live but did not openly promote or propose it as a complete solution the wider human population. It appears that those people who consciously end their lives, have extinguished their will to live after coming to terms with the fact that life is a state of various kinds of suffering and also an endlessly replicating cycle without any clear end result, i.e. living or not living has absolutely no impact on the state of things in the universe. No matter how far human civilization goes [for e.g. colonizing planets in the universe], the same cycle will be repeated endlessly without any clear end objective, i.e. human beings would replicate everything on Earth on those planets and continue to mate, reproduce and pass down the task of finding sense to life to the next generation; we would invest tremendous resources to reach other planets [e.g. developing artificial intelligence, creating sophisticated and articulate androids with human-like capabilities, developing cryogenics or some other technical solution to survive journeys that may last from 50 to 100 years or more], and once there, we would build houses, roads, restaurants, shops, an economic system, create jobs, etc.

In the case of people who become completely aware of the manipulation imposed on human experience by the “Will to Live” and make the conscious choice to extinguish it completely, the continuity of the human race or the survival of his fellow humans have absolutely no importance or meaning since life has no sense to such a being because it simply replicates for the sake of replicating itself – in the cosmic order of the universe we are nothing but atoms, or space dust.

The final and fundamental powerful point to keep is that thanks to Schopenhauer’s philosophy, we can at any moment we choose to detach ourselves from all of the most violent emotions and feelings that inhabit our thoughts simply by reminding ourselves that our “Will to Live” (i.e. survival instinct) is simply manipulating us.

A constructive critique for joie de vivre & progress

A reason to live for the human race

We can base ourself on the observation that if atoms from space dust in the universe collected on a very specific planet known as Earth where the atmospheric conditions are perfect to allow the transformation of those atoms into living cells which over thousands of years became more complex to eventually give rise to human beings, then there must be a hidden force that lead to this creation. In that sense, we can also question this creative atomic force and meditate forever about the reason behind our creation. The explanation from the Christian bible about the creation of man by The Lord God from the dust of the ground comes across as a great metaphor since all life is made from matter.

Some people may link this creative force that sparked life on our planet to the notion of divinity and the process of creating life. So, on that issue if we were to allocate reasons behind every form of creation, we can assume that the cosmic forces of the universe had a reason for creating humans and as such, those forces that may be linked to the divine creation and wanted us to live, and may have planned for us to achieve some form of task in the story of the universe. This, I believe, makes a case for the human race to value surival and continuity, even if we are unaware of any final objective or final result that our continuity will lead to. Perhaps one day, we will understand why we were created and why we are the most sophisticated lifeform on this planet, unmatched in terms of intellectual abilities by no other species known to date.

The Right to Choose a Mode of Existence

Every individual should have the right to choose how to experience life and it would be extremely arrogant to impose a particular model of living or a particular mode of existence as the ultimate way of being. If an individual chooses to restrain his “Will to Live” to the limits of extinction and wishes to experience life through his organic body in a minimalistic and spiritual way as some people in Asia do, then it is a choice as valid as any other, moreover those people are not asking anything from others and are not imposing this mode of existence of humanity; it is a matter of personal perspective and desire in line with a vision to discard what some see as an existence of suffering and desiring endlessly in the industrialised world. Whatever the reasons behind the choice of an individual to live such a minimalistic life by repressing their “Will to Live” [or survival instinct], as long as it is personal, it should be respected. Among those personal reasons, may also be the choice to not replicate life to endure various forms of suffering, and this may be a reasonable and admirable choice for individuals who unfortunately are not in the best conditions due to a range of factors, to bring a new life into this world and provide it with the best chances to prosper and live a fulfilling existence.

According to the epicurean school of thought, pleasure is the absence of suffering, and in order to stop suffering, it is a duty for individuals to question whether it is fair to create life when the conditions awaiting mean struggling through various kinds of hardship.

There is only a limited amount of living space on our planet, and the issue of population growth being mismanaged and unrestrained should be a great topic of concern for humanity to reflect on as the world begins to deal with the question of over-population which will only cause extreme mass suffering when also having to deal with the problems of climate change that will lead to many catastrophic environmental disasters in the future (e.g. limited resources to feed a dangerously growing population). For example in many poor regions on the planet, for e.g. Africa, the population growth has been steadily increasing despite the lack of resources to provide an adequate and respectable standard of living to the new born, who come to the world only to suffer due to the lack of family planning. Hence, this topic should be the concern of all respectable community leaders, and should raise the urgency for providing education about family planning.

A Sense of Concern for the Survival of Homo Sapiens

Complete detachment from our feelings and emotions once an individual extinguishes the “Will to Live” can lead to suicide, which is nonsense. Complete detachment may also lead to a mind that is stale and completely devoid of any form of reaction to any external event that is not connected to the organism that is in such a state, this would also lead to a lack of emotions, for e.g. compassion and empathy (since those are the products of the ability to feel the pain of others and react to the emotions and feelings elicited).

If an individual discarded the “Will to Live” completely, it would also mean discarding the very behaviours linked to the “Will” that are responsible for the survival of homo sapiens, which lead us to protect our fellow human beings [i.e. the evolutionary purpose of emotions and the ability to feel].

The individual who kills the “Will to live” completely would also have no sexual drives, which would also not promote the survival of the human race as there would not be motivation to mate and reproduce. In that sense, if the whole population were to choose to completely extinguish their will to live, it would lead to the extinction of homo sapiens (i.e. the human race).

Engineering our Modern World in Harmony with Nature

The evolution of our species has led to the development of its various intellectual abilities and eventually given rise to the modern world, which took homo sapiens out of the primitive lifestyle from the caves and the jungles and into settlements of the modern world with a range of facilities, for e.g. sophisticated healthcare, education, technological advancement, legal protection, literary and artistic developments, to name a few.